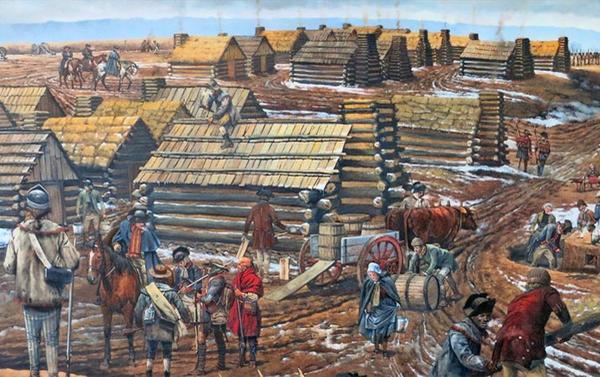

Twelve thousand men were in serious trouble, despite the onset of spring in 1778. The Continental Army was already in dire straits after several brutalizing defeats through the autumn of 1777. Most lacked uniforms, and some walked barefoot, wrapping rags around their frozen feet. They were sorely in need of basic gear or victuals to survive the winter at the junction between Valley Creek and the Schuylkill River next to a remote iron forge in the middle of the Appalachians.

The place became known as Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

Contrary to folklore, the winter of ’77-78 was not exceptionally cold (that happened the next winter at Jockey Hollow, in nearby New Jersey). Temperatures were often above freezing, and snow cover was minimal. What was brutal was the appalling lack of supplies for basic living: food, clothing and blankets. Disease was rampant despite nearly 1200 rough huts that isolated troops in tiny quarters. Sanitation was poorly followed, and hundreds of men perished from dysentery, smallpox and cholera. The concepts of germ and contagion were still poorly understood, and the crowded and malnourished troops in unventilated and cramped cabins were perfect hosts for bacteria and viruses.

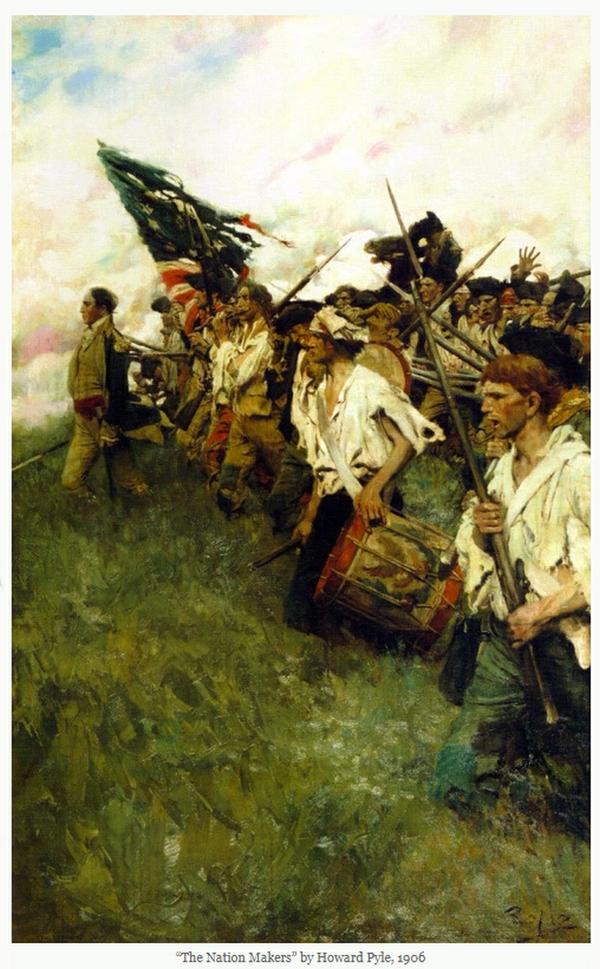

Disease further exacerbated the disunity in the ranks. Many people today believe that the troops that comprised the Continental Army were predominantly English in descent. It was simply not true; there were at least 5 languages spoken commonly in camp. At least 10% of all troops were estimated to be African Americans, many of whom were promised emancipation when they signed up. There were Frenchmen, Spaniards, Portuguese, Germans, Welsh, Scots, Irish and Scandinavians. Native Americans of Senecan and Oneidan tribes provided much needed scouting and woodcraft abilities to the force. It truly was a melting pot of great diversity. Today, we say there is strength in diversity; indeed, it is true. But linguistic and cultural barriers proved fertile ground for the seeds of prejudice, and it grew well in the climate of disease and starvation.

The horses went first. Twelve hundred died in the first several months from starvation. There simply wasn’t enough grassland forage in the timbered hills of Pennsylvania. Troops ate what horses they could.

Some historians credit women for keeping the death rate over the winter at only 10%. Several hundred simply moved in with their men for the winter, missing their husband or love. Many were pregnant and bore children in the fetid living conditions. Even George Washington’s bride, Martha, moved up from Virginia for part of the season to stand by her man through this trying time for troops and the ideal of Independence.

Just by their presence in the huts, females raised the standard of living. They washed, cleaned and cooked for the men, and created an environment for the troops that warranted a cleaner existence. Males generally keep cleaner and more organized around women (I have seen this in my own crews on Alderspring). It is believed General Washington recognized this; as a result, he reluctantly allowed their presence due to the morale and sanitation boost that women offered.

Just by their presence in the huts, females raised the standard of living. They washed, cleaned and cooked for the men, and created an environment for the troops that warranted a cleaner existence. Males generally keep cleaner and more organized around women (I have seen this in my own crews on Alderspring). It is believed General Washington recognized this; as a result, he reluctantly allowed their presence due to the morale and sanitation boost that women offered.

Women weren’t the only factor that saved lives in Valley Forge. There was an unanticipated ally silently gathering its forces to support the Continental Army. These supporters of the war effort found residence beneath the cold and slate-gray waters of the North Atlantic. More on them later.

The lack of good transportation over great distances simply meant that the 12,000 troops and the women and children with them exhausted the landscape around them of vital food supplies; this of course, got worse as the winter progressed. This was in a day where there was no refrigeration, and foodstuffs often spoiled en route to the Army, despite winter temperatures. Wheels fell off wagons. Oxen teams got mired in mud and snowdrifts. It was a logistical nightmare. One recorded bright spot was when a score of women (nearly all able-bodied men in support of independence were troops) arrived in camp with several hundred fresh shirts and blankets—borne by 12 teams of young and fat oxen. Their patriotic deed realized, the women either stayed on at camp or went back home. The shirts and oxen were gone, put to use by cold and hungry troops in a matter of hours.

The turning point for the troops came on the back of a warm spell. Early heat hit the gray Pennsylvania hills with unseasonal warmth for the month of April that bade change for the long Valley Forge winter. It was so warm that the temperature of the waters in the adjacent Schuylkill River rose by a few degrees. Frostbite became a memory. Trees began to bud, and even bloom. One such tree is called the Shadblow.

Shadblow exists throughout the North America in 3 or 4 species (plant people like Caryl argue about such things). It is in the rose family, and its subtly sweet-smelling white flowers signal the final demise of winter. It blooms in response to day length and rising soil temperatures. It is a small, noble tree with smooth gray and darky striped bark, elegant in the understory of the hardwood giants that would all fall over the next hundred years to the lumberman’s axe and saw, propelled by an insatiably ravenous industrial revolution. Nobody cared about the shadblow. Lumbermen simply cut it down or ran over it with wheels that grew bigger and stronger with each passing year.

But for now, in the spring of 1778,  Shadblow continued with its humble life, roots firmly anchored and suckling on earth’s breast of rocky soils like those along valley bottom watercourses. It is no mighty oak. It tops out at a meager 40 feet, and with a trunk diameter rarely above 6 inches.

Shadblow continued with its humble life, roots firmly anchored and suckling on earth’s breast of rocky soils like those along valley bottom watercourses. It is no mighty oak. It tops out at a meager 40 feet, and with a trunk diameter rarely above 6 inches.

About 40 years ago, I remember finding one along the Appalachian Trail’s miniature basin and range rolling hills topography of Southern New York State. I’ll never forget it. I still remember putting my arms around it and feeling the smooth striped gray of the bark pressed against my chest. As a student of trees, I knew trees fairly well, and if not for the flowers that it bore with the first warm days of spring, I would not have known it because of its unusual size. My specimen was about 18 inches in diameter, and 40 feet tall.

One look that the National list of Champion Big Trees told me that although my find was in the top 2 percent of all shadblows, it wasn’t great enough to be a champion (the current one resides in nearby Connecticut). It will always hold a record in my mind, though. I think if you challenged me to find it again, I believe I could relocate it, despite it being miles from the nearest road or habitation (I hope there are still parts of forested NY state that are like this).

I’ve planted many shadblows. In my younger forestry and nurseryman days, it was all I knew them as. They became familiar friends. Then, as usually happens in college, at the University of Maine, provincialism that gave place-specific names to trees died a sad death, buried by so called University wisdom. Shadblow became serviceberry. Then, study and coursework in the science of dendrology replaced that common name with the preferred language of botanists: Latin. Amelanchier.

But in my travels, I learned more of the local lore of this beautiful tree. Saskatoon. I had never heard of the word. It stalked into my vocabulary on a rainy night, in the mid-eighties when my car began losing headlight beam in the middle of the Saskatchewan prairie just after passing a sign that directed the way to Saskatoon, the provincial capital. I stumbled into an auto electric shop in the small town of Moose Jaw on a Saturday night, hoping to find a much-needed alternator. From the shadows of a dimly lit shop, on the other side of a tool and parts cluttered workbench, a voice spoke out despite the din of the pouring rain on the tin roof. It was David, the owner of the shop, still intently tinkering on a random electrical part. He was spending Saturday night in Moose Jaw. Cut that rug.

David built me an alternator, then and there (I checked online, and he is still in business, 35 years later. He has 2 five-star reviews on Google). By midnight, I was gone, eastbound on the Trans-Canada (it was two lanes then).

South of Saskatoon, the provincial Capital. Peculiar name. After asking around, I found that the prairie province’s seat of government was named after a berry borne by the same humble tree of other names: shadblow, serviceberry and Amelanchier. Shadblow had found itself on the edge of the great north woods; surviving on granitic soils next to the multitude of pothole prairie lakes.

Then, much later, as I worked in the Western Rocky Mountain timberlands with loggers in the Douglas-fir, Saskatoon became Juneberry, appropriate for the lovely blueberry-like fruit borne along watercourses.

Now, after 30 years in this place, there’s been many times where I’ve leaned into a ripe Juneberry bush on horseback, while moving Alderspring beeves on the high mountain ranges. I snacked on the ripe berries before the bears and birds got them (often, in June in Idaho’s mountain country, you’ll see branches and trunks of juneberries split by the weight of greedy post-hibernative and engorged black bears).

And now back to the starving troops at Valley Forge, thousands of miles distant.

The tree is the same. It speaks the same language.

The tree is the same. It speaks the same language.

You see, when George Washington’s beleaguered and ragtag troops noted the shadblow in brilliant and creamy-white bloom with the early onset of spring, they remembered what it meant. For the name of said bush was not in vain: the bush was viewed as a sort of herald. For the “blow” of the herald’s trumpet was the creamy white blossoms that cloaked riverside forests, and they signaled the time when the suddenly ice-free rivers bore a warming meltwater message to the lowly shadfish, waiting at the edge of the deep Atlantic’s continental shelf for idea spawning conditions.

Awakening and returning from the vast ocean after 3-6 years, the shad clogged rivers like salmon, returning to Appalachian tributaries to spawn. Some traveled as much as 950 miles upriver across the Appalachians. Literally millions upon millions of the silver sided fish surged into the Chesapeake and Delaware bays, heading to their birth rivers.

The British were wise to it, and actually tried in vain at Philadelphia to stop the rush of shad with a log and brush blockade all the way across the Delaware from Pennsylvania to New Jersey. They knew what it was: a piscine wall of protein that ultimately would feed a desperately waiting army 25 miles to the north of them at Valley Forge along the Schuylkill River.

The shadblow signal was right; within days, the fish arrived. And they fed thousands of men, many of whom were at the brink of death. Some say shad saved the Continental Army, perfect protein delivered to an otherwise hopeless lot. There’s no telling how many more men (and women and children) would have perished at Valley Forge. They had been largely living on corn and wheat (some rotten and moldy) cakes formed of water and coarse flour, cooked on hot rocks by the fire’s edge.

Those who survived that winter (and didn’t join the multitude of deserters) were galvanized. Historians today say that Valley Forge was a turning point. Survival provided to them mettle; a staunch resolve that eventually proved too much for the British. And the diversity of American forces became more than a fly nuisance buzzing in the ear of King George III; it was now a swarm of bald-faced hornets.

Back in Idaho, 240 years later, The Salmon River canyon has little puffs of white fog in it today, despite the azure sky being cloudless. It is the Juneberry, cloaked in white blooms that dot the hillsides. Full Latin name: Amelanchier alnifolia. These ephemeral paint-splotches of white are the first flower showing after a long Idaho winter. This past week has been an exceptionally brilliant display, brought on by a 70-degree warming trend that broke the icy grip of winter, once and for all.

As we drive the serpentine road along the Salmon River Canyon (200 curves per hour, by last count), we occasionally stop to take the bloom in. It’s a rite of spring for Caryl and I. We cut some emblazoned stems, and put them on our kitchen table, and inhale deeply of the quiet and subtle fragrance that dispels winter’s scents.

To me, they’ll always be shadblow. I get perplexed looks when I mention them, even to seasoned flower and tree lovers in Idaho. They’ll think I found a new tree. And when I explain that it is also called serviceberry or Juneberry, they’ll quickly forget my former name for the gray barked smallish tree of river rocks.

But I won’t. Because things could have turned out very different if it wasn’t for the turn of events heralded by this humble tree. You see, there are so many things in nature that carry meanings and story for our lives on this earth. They bring color and quiet to our consciousness in our too often cold concrete and metal machine lives. We get swept away by technology and what’s trending. I think we all need to stop and smell the subtle scents, like that of shadblow.

It is a thing that keeps us going on Alderspring. Oftentimes we have a financial setback on the ranch or webstore, but then we need to step outside and get our hearts and minds adjusted with the reality of our surroundings. We live in and with nature; often, we are part of it. Our beeves have a wild existence, and as their stewards, we immerse ourselves in it, and bring you wild protein.

Oh, and then there is this: to get your wild protein, you no longer have to wait for the river to bring it. Technology does have some benefits. We will mail it to you by that infrastructure we lovingly (usually) call Big Brown.

Happy Trails

Glenn, Caryl, Girls and Cowhands at Alderspring

Leave a Reply