Summertime is here on Alderspring, and the living is not quite easy. It’s not in a bad way, but the long days make for well…long days. Sometimes I feel like a bear foraging hard through the summer trying to build that winter fat so we can rest a little come winter. In fact, the beeves are even more bear-like as their biological clocks are set for full diurnal, meaning they will graze every daylight minute they can, given some breaks to chew cud, or what we call ruminate. It means we have to ride all day with them on the range. Most of the crew has settled into that fact, but even still, they jealously guard their sleep and eating time and get a little edgy when they see either start to erode.

We had visitors this week. They came from Europe on behalf of a well-established and highly rated eatery. There was Tomas, the co-founder and CEO, executive chef and Michelin star recipient, Martin, and foraging consultant Marc. They also had in tow a videographer and producer, Pierre, who recorded the visit for posterity.

To put it simply, they came in search of beef. In a taste test in Manhattan in March of this year, Alderspring had scored highest against 5 other leading grass fed and niche producers from around the US, and the guys wanted to find out the why and how this could be. Unlike most of the other entrants, it is just Caryl, the girls and me, who together with our fine crew of 6 college age summer cowboys raise Alderspring beef. Most of the competitors we steak tested against were corporations (one was multinational) or large cooperatives.

After an exhausting transatlantic and transamerican journey by airline, they rented a new black stealthy looking Suburban for a comfortable trip up. The guys experienced a full immersion into Idaho mountain redneck culture on the way up, with a stop in New Haven Cafe, in the lonely hamlet of Lowman, Idaho. Their stomachs, although uneasy after driving the numerous hairpins of Idaho 21 for the last 90 miles, were soon stabilized and satisfied with Fred’s home smoked brisket sandwich served in a diner liberally decorated with NRA and gun rights posters. Our friends were fascinated, and perhaps a little unsettled, but Fred and his wife were very nice to our gunless visitors and wished them well on the remainder of their journey to the ranch.

They met Caryl and me at our Salmon River rendezvous point 3 hours later after driving through the wilderness of some of the most rugged and snow speckled scenery in the lower 48 states: the Sawtooth Mountain range. Little did they know that they would soon experience their own total immersion in a wilderness setting. After handshakes all around we had a little back and forth about which vehicle to take. They wanted to take theirs, a little dubious perhaps, of the 20 year old Alderspring suburban. I prevailed, mostly because I knew my high clearance and rubber and lug steel tired suburban had a good chance of making it, while the road driving efficient tires on their rig would likely be all flat in the first hour or so of rock-strewn driving.

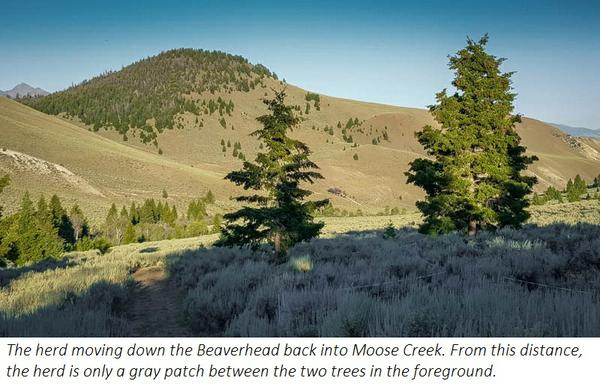

It was a long and rough 2.5 hours that got us to where we could first see the cattle and the cowhands, pasted on the side of a steep mountainside, high above Moose Creek. I looked in the rear view mirror at upturned faces as they took in the scene. They pointed out cowboys and cowgirls around the herd perimeter, carefully picking their way through the brush and volcanic rocks on the sides of Moose Creek canyon.

Upon arrival at Moose Camp’s setting in the shade of stately Douglas-fir trees, the disparity of this place and time from their everyday experience became irrevocably clear: there was no cell service, wifi, or din of traffic. Indeed, it was the farthest from humanity any of them had likely ever seen. It was the first time I had gotten a vehicle to Moose Camp. The trail up was incredibly rough, and everything for our current crew’s life support up there was packed in on the backs of packstring horses before we showed up.

We quickly set up tents for the travelers, as light was beginning to fade. Wisps of dust in the air down canyon could be seen as the cowhands quietly brought the herd to their night bedding ground near camp. I Iit the lanterns under the open-air kitchen fly as we began to cook dinner while night settled in. First order of the evening after refreshing our dear travelers with a drink of their choice: Alderspring ribeye. It was an important stage setting activity, as it would validate their reason for coming here in the first place. They needed to know that their earlier test in March was not a fluke and were testing for consistency over the season of Alderspring. I pulled the thick and well marbled ribeyes out of the cooler and handed them to Martin. He happily took them and began to prep them for the grill between sips from a lager. The grill consisted of a steel grate over a rock fire ring just outside of the kitchen canopy. Martin and I built a small, native American style fire, and placed charcoal chunks around and in it for coal longevity. The Michelin star chef liberally crusted the steaks with flaked sea salt (no other seasonings), and as the coals set, and the fire died, he placed the steaks on the grate about 8″ above the now glowing coals

Martin clearly knew the grill and steak more than anyone I had witnessed. In spite of the surroundings of wilderness, he fell right into the familiar instincts and practice of parilla style cooking in which he had world renown. As the ribeyes emerged from charcoal heat to the resting plate, the full consequence of the Mallaird reaction (browning and subsequent caramelization) filled the camp with the fragrance of the marriage of fire and steak.

I digress, now, because while my friends were standing there oblivious, my mind is on ursine alert. In other words, I have a problem with bears. They are always on my brain. I have had too many encounters with our ursine friends, and not all of them went well, resulting in risk to life, limb and camp. They, like us, are opportunistic carnivores, and I am quite sure they like Alderspring beef (I believe they especially have a penchant for grassfed). I cast continual sidelong glances into the forest with flashlight beam, searching for the wandering eye of bear with bravado. Just 4 nights ago here, I spotted a mountain lion sprinting across the sagebrush and away from cattle and cowboys. Large predators were common in Moose Creek.

Taste test number 2 commenced. Cameraman Pierre was all over us with his rather large and state of the art Sony video marvel. As testing and filming progressed, Pierre began to display the beginnings of disgruntlement with his primitive surroundings (no power, no charge, no data manager, no sound man, no light assistance). As the weary and dusty cowhands drifted into camp on tired horses, pulling gear by firelight, I spotted them often looking over shoulder quizzically at the foreign and accent-heavy entourage. The visitors’ attempt at cowboy hats was especially interesting.

The steaks were ready. Several ribeyes from different beeves (black Angus, on the range last year, and red Angus, off the ranch headquarters) tested exquisitely. Both CEO and Chef agreed that the steaks produced some of the finest beef flavors they had ever experienced; even so, they were sure to leave some for the cowhands. I presented a nice Dutch oven dish of baked beans (to die for, said Chef) prepared by Caryl. Linnaea got off her horse and unveiled a cheesecake she made from scratch; Marc cracked open some nice Malbec to wash it all down. It was all we needed.

Tomas went right after the dishes, and all pitched in to clean the rest up and make it bear secure. Night animal sounds permeated the camp as a bigger than life moon illuminated the forest floor with an ethereal glow. Everyone chose their tents except for me and forager Marc who preferred open air, in the great outdoors. Tomas asked me about it as he made his way tentward.

“No tent for you, Glenn?”

“No. I like to sleep on the ground, right here in the middle of camp, with a gun on each side of me. That way I can grab shotgun or revolver with ease, even as I lay in my bedroll.”

I looked up from dishes I was putting away to see Tomas’ penetrating and silent gaze toward my eyes, waiting for mine to meet his own. He cocked an uplifted eyebrow. “For what reason, may I ask?”

“The last time I set up cow camp in Moose Creek–I didn’t tell my crew this–I noted that every rock I could find in the forest around camp had been turned over by a bear within the past few days.” I put some more clean dishes away and proceeded to douse the fire. I met his unwavering stare. “He or she had been taking inventory on grubs and ants under the rocks…and eating every last one of them. So we could have hungry bears around here, and since black bears are very unpredictable, and we have been cooking up some great aromas of Alderspring, I was concerned that one may want to join us tonight. Killing anything for me out here is an absolute last resort, but a little birdshot from shotgun barrel in the air or, if need be, on his butt will send a message that he is not welcome here.” I poured a little more water on the steaming coals. “Don’t worry. The bird shot won’t penetrate his hide, but it will smart. We just got to send a message to him that sharing camp with us will never do.”

Tomas smiled nervously. “Well…good then. Anything else?” He started to turn toward tent, then halted as I began to speak.

“Actually, we had heard a wolf at the last camp, and if they come into the bedding ground tonight, I’ll have to wing a few rounds over them skyward to send them off.”

He turned back toward me. “Is that all?”

I nodded. He turned and took a step back toward me, his eyes meeting mine, and pausing, as if for effect. “Have you seen The Revenant?”

“No…I haven’t.” I stirred a shovel through the wet coals.

“It’s a movie I saw last week. Leonard DiCaprio plays a guy who gets absolutely mauled to pieces by a bear.” Tomas was not smiling. Not even nervously. “It’s supposed to be true.” Waiting for my response, perhaps a placating bone I may throw his way.

No can do. I could hear the hot rocks sizzling as steam wafted up from the dead fire.

“Well, good. Goodnight, then, Tomas.”

“Good night.”

Exhausted, we all fell into bedrolls. It was 1 am. I woke several times that night as red army ants found their way into my bedroll. Apparently, I had set down my bed on their convoy trail of formic acid secretion and they were confused in the warm bodied mountain that lay across their path (I usually check). The cattle slept uneasily as well: they all stirred once on bed ground, and I heard the start of stampede. Then, abruptly as they began, they stopped, still in their night paddock. When I awoke the next morning, 2 of the horses were out of their hotwire pen and free, wire strewn across sagebrush meadow. No clues as to the troublemaker.

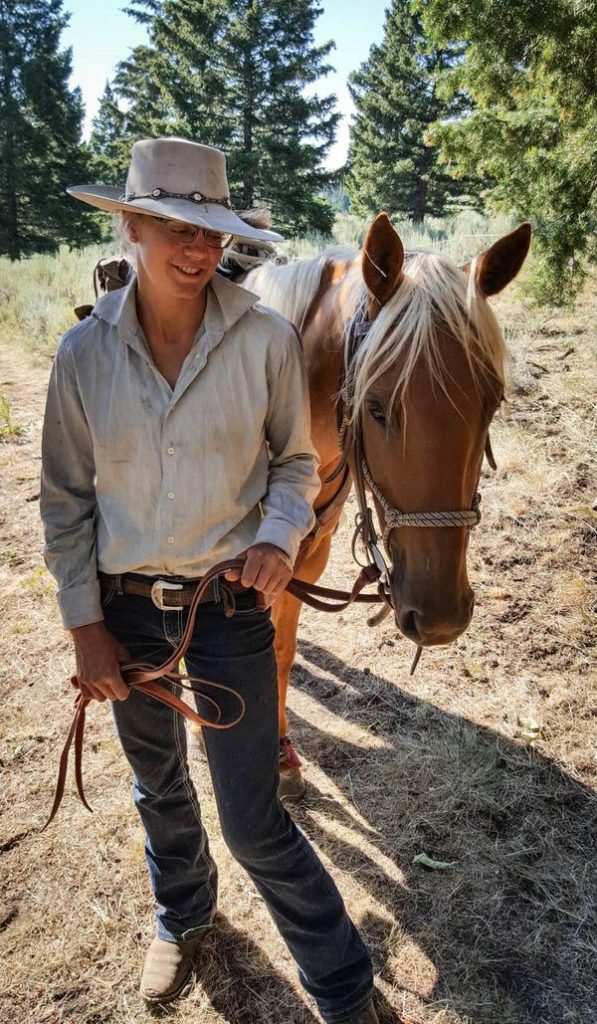

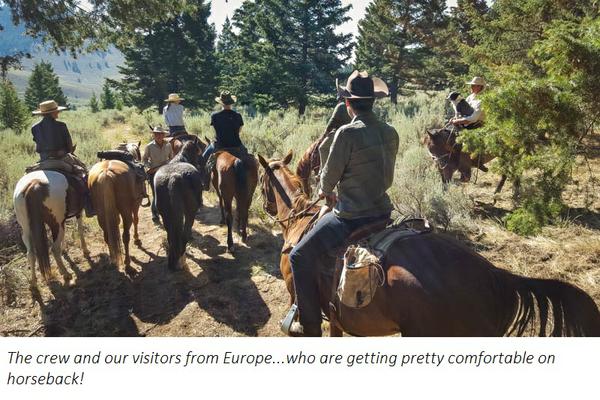

The morning sky was crystal clear. It was our visitor’s first day on horseback. I felt it was important for them to get the feel of the Alderspring landscape, and how we handle the beeves. Cowgirls Melanie, Abby and Linnaea got the greenhorns squared away on tack gear and chose mounts for them from the remuda (horse herd) that roamed around the night ground near the cattle. I assigned a girl to each rider to keep them honest on horseback, with the exception of Marc, who had some experience. One small mistake could mean a wreck in this rough country, but I have to hand it to their foreign charges; they all took to it very well.

Soon, we were saddled up and away, getting the herd a deep drink from Moose, and heading up the opposite mountainside. Dismissing some occasional dicey body balance and saddle sliding moments the restauranteurs did very well, and were continually in awe at the wildness and expanse of the rugged Hat Creek ranges. I watched the crew eagerly share the treasure of the country that they had long known. Our guests rode much of the day, and even spotted other range residents: elk, mule deer, coyotes, sage grouse, and goshawks. We pushed our way through thick pine forests both open and filled with jackstrawed downfall, sagey meadows, and open aspen glades.

The ride was pretty uneventful until we reached the beaver pond at the junction of the two forks of Moose Creek. There was no choice but to cross it.

It didn’t look too bad. The beaver pond had subsided since the last time I had been here, and elk and deer kept a nice trail open through the dense aspen forest. The only problem was some down timber choking the way, making a barrier of around 3 feet in height. I brought my tall buckskin mare down there first, but she chose to jump clear over the logs in one shot. We landed in the beaver mud hole on the other side, splashing mud, but thankfully on all fours. I wheeled Ginger around and cautioned Tomas, who was next, to get off and lead his mare across the swamp while he balanced on a slippery log. He soon lost balance and fell into the dense undergrowth, pulled downward by his stubborn April mare who wanted to forge her own way ahead through the mess. Tomas’ designer jeans got a little mucked up, but he was soon recovered and remounted.

Marc had it a little different. His mare (who can be bitchy) noted him leading the way and soon bowled him over, hoping to use him as a bridge across the beaver made mudhole. She almost succeeded, and he came out with his designers redesigned (the mud look is just coming in, I’m told). Chef Martin did the best, staying bravely mounted, quietly letting his gelding go calm and cool, squishing through the mud. Chef and gelding George made us all proud.

Soon after the mud bath, the visitor group arrived early at camp to fulfill another desired another attempt at Alderspring: short ribs over the parilla, slow cooked until late in the night and just in time for the cow crew’s arrival with the herd. The fatty and flavor-filled short ribs met well with Tomas’ lemon zest slaw and Linnaea’s stacked Dutch oven yields of baked then grilled focaccia and deep dish peach/blueberry and wild gooseberrry cobbler.

As midnight came and went, both cowhand crew and the visitors were exhausted, partly with the physical demands of horseback all day, and likely altitude of some 7000 feet. Muscles they didn’t know they had ached. Some ibuprofen was passed through the ranks, and light alcoholic medication cared for the rest. I was grateful that we didn’t have rain or snow on us during their stay, as weather can push already tired bodies to the end of their ropes. I have seen anger or even tears of fatigue and frustration often set in like dark clouds over range riders, and I was grateful I didn’t witness it in my visitors.

As he was turning his tired frame to his waiting tent and bedroll, Tomas stopped on the way there to speak to me.

“I just want to thank you again for having us. This has been an absolutely wonderful visit. The country is absolutely amazing, and what you do here with the cattle is incredible.”

“Well, thank you for taking the time to join us. We have learned a lot as well by seeing the range through your eyes.”

He smiled. “You know, this trip has a series of firsts for me. I’ve never before been on a horse, I’ve never camped out, and I can’t remember when I have been unreachable by anyone. In fact, if I was to try and conceptualize a life completely opposite from mine, I realized I would not have to.”

“Why not?”

“Because you are living that life.”

It was true. I knew that his life back in the EU was a polar opposite from ours. But that didn’t prevent Tomas from finding a connection with us–as fellow humans living with horses and cattle and sharing a wild landscape. And he could take a small piece of it with him in the form of beef, and thereby share in the gift that the land presents to us in great food, that perhaps one day, he will share with others. And, when called upon, both Chef and CEO could be able to share firsthand the story, because the strongest of memories, of stories recalled, are associated with the sensations of flavor and fragrance.

Thanks for letting us share that gift of story and beef with you.

Happy Trails

Glenn, Caryl and girls on Alderspring

Leave a Reply