I’m sitting here with my office window open on this fall evening in the high Pahsimeroi. I take notice of the quiet outside in the thick evening air left by the rain that fell on the ranch last night. The summation of sound is crickets making that last ditch late summer effort at finding that mate, and distant magpies arguing over whatever they argue about. Their chatter is carried in on a silent breath of mountain air heavy with the fragrance of bloomy alfalfa and horseflesh grazing nearby.

I haven’t always lived on a ranch. I’ve been in other places in my younger years–places full with the cacophony of humankind: New York suburbs, where the low din of traffic never fully silences; Michigan slums, where the regular sound of sirens on sweaty, broken and buckled streets would be occasionally punctuated by the crack of drug lord gunfire. The comparison of our current situation of quiet with some of my noisy past keeps me from that place where I could take what is here for granted.

In retrospect, I see now that even some of the seeming peaceful country settings where I have lived carried an undercurrent of noise: Wisconsin dairy cows necessitated near continuous running of equipment to feed them and pack their effluent; Indiana corn and soy fields required frequent tractor visits to till, seed, fertilize, and chemically eradicate interloping plants that would attempt to make a home in the monoculture of corn or beans.

So much of this country noise could be traced to one 20th century invention. It was the thing that created the reason and culture of corn and soybean in what was historically the tallgrass prairie–the endless sea of grass, with waves of big bluestem so tall that a man on a horse could get hopelessly lost. These seemingly endless waves of grass diversity grew on black soils as deep as 50 feet. It was why 50 million head of bison thrived in the prairie–nearly twice today’s annual nationwide production of beef.

This apparently innocuous invention changed the fabric of rural America, slowly at first, but as with all things exponential, change came like a tidal wave over the Midwest. Vibrant towns soon found themselves population poor; stores on Main closed, never to reopen. Farms were consolidated. Grazing animals were removed, and Farmer Brown made his final trip to the slaughterhouse, with no pastured progeny left on the farm’s pastures. No livestock meant that there was no need for fences. Fields were enlarged and flattened, ponds filled and fencerows straightened or ripped out as farming equipment technology demanded it; big and better iron machines now ran faster and wider. Pastures disappeared, and those meadow soils became dirt, forever married to the plow and disc. The long reaching results of this invention caused unprecedented waterborne sedimentation and nutrient poisoning of the Gulf of Mexico and the Mississippi Delta; in fact, the invention gave Monsanto a job in its incessant tinkering with corn.

The invention? It was the feedlot. As Wendell Berry eloquently observed, removing animals from pastures and placing them in feedlots takes something quite elegant—beeves replenishing the fertility that removal of forage depletes—and creates now two problems: a lack of fertility in pastures and farmed ground and a nutrient pollution issue in the feedlot. The first issue is superficially fixed with non-renewable petroleum fertilizer; the second issue has been the bane of watersheds and coastal deltas.

Wendell Berry’s observation is actually a great oversimplification; there are a plethora of other issues that make feedlots a poor idea. One of the most significant for me is that the feedlot and cornfed model is not good for animals. In fact, if beeves continued to stay confined on the high energy ration that typifies America’s feedlots, they would die there in no more than a year. We have cows live on Alderspring until they are 18 (That’s somewhere around 100 in people years).

It’s not even economic. Last week, I received a histogram from Jim Gerrish, a nationally recognized expert on the grazing and raising of cattle that showed that the 15 year average profit per head in US feedlots was a negative $41.94 per head. In spite of the red ink, the juggernaut continues. In fact, US beef interests are now busy converting the some of the greatest grass fed beef economies in the world found in Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay into corn based feedlots. It’s too late, by the way, if you feel your activist side rising up in you. Already millions of pounds of USDA stamped boxed feedlot beef from South America enters the US every year. The silent transition from grass to corn in the New World part of the Southern Hemisphere is nearing completeness. And you won’t even know you’re eating that South American beef. With the repeal of Country of Origin Labeling last December, the beef in your local market can be from anywhere.

****************************************************************

An inspector from Idaho State Department of Ag showed up the other day to look at our corrals, and see if there was any potential for effluent from them to reach critical salmon habitat in the Pahsimeroi River, over ¾ mile away (there wasn’t) He noted the five cows we had in there (we have a few old cows we hold there that we don’t want mounted by bulls outside). He saw the huge containment pond that we put in just in case we have a rain on snow event, and overland flow happens. It was dry. I told him that we flood it with water from our well and use it for a hockey rink in the winter. He smiled at either the hockey or the overkill we had undergone to protect the river–just in case– as he leaned against his truck, eyeing the fenced area on this beautiful fall afternoon.

“You still raising that organic grass fed beef, Glenn?”

“Yep. Steady as she goes.”

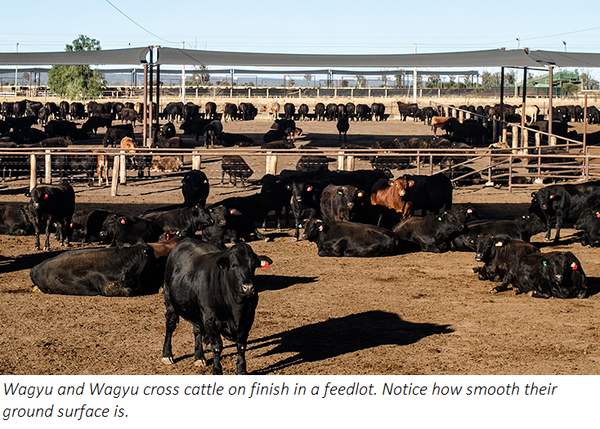

“You know anything about that Wagyu beef? They call it Kobe or something. I was in some of their feedlots down southern Idaho last month.” He squinted in the afternoon low angle sun, and turned to me. “You really ought to see that sometime.”

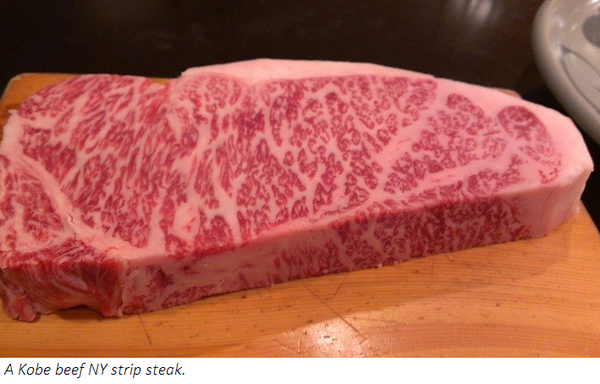

I knew what he was talking about. American Kobe beef was a variant of Japanese Kobe, raised in Japan. Producers in both countries raise purebred Wagyu, a Japanese breed known for its very easy marbling. Steaks like ribeyes or filets are laden with cream-white streaking and teardrops that stretch the term marbling to new proportions with as much as 60% fat content. Tenderness, and a purportedly great flavor rendition because of the vehicle of fat on the tongue are its hallmarks. It’s grown in feedlots on high-grain rations. The fat is very high in Omega 6 fatty acids, so you are quite likely to have a cardiac on a fare comprised regularly of Kobe. But it certainly was said to be an experience if you could stay out of the hospital.

“Why do you say that I ought to see them sometime?”

“Because they are pretty awesome to look at…I mean, well, they are so fat, I mean so fat, as in obese. I saw this one pen of steers weighing close to a ton each. It was incredible. And the grooming”¦”

“The what? Did you say grooming?”

He turned to me and looked me in the eye. “Sure did. They spent quite a bit of time on it.” I knew that in the legends around Kobe beef, Japanese beef artisans keep their steers in small pens to encourage the greatest tenderness by minimizing movement. Word was that the most serious handcrafters of Kobe massage them from time to time, and pour rice beer and wine in their mangers (Alderspring beeves are teetotalers, if you’re wondering). Maybe grooming is an important part of the process, I thought.

“On that grooming”¦?” I drifted off quizzically.

He turned back to our corrals, and pointed. “Yeah…see those rocks and bumps in your corral? They would be totally unacceptable. They get a tractor in there every day with a grooming tiller on the back of it so that the feedlot surface looks like a pool table.” He turned and looked at me in the eye. “Well, you know, Glenn. You just can’t have those bumps in there.” He stopped talking. He just smiled patiently, waiting for my light bulb to turn on.

It finally did. I slowly began nodding in understanding. I’ve never been real intuitive on math, but this equation was adding up as I was brought back to my mind’s eye of a sad time. I recalled an old cow in particular I had years ago that was 9 months pregnant and ready to calve, and was pretty heavy. I found her dead on one of those spring mornings, caught with her back against a rock. It’s one of those things that has a photograph attached to it in your mind. She had chosen a bad place to lay down, and in her heaviness (maybe with twins), she couldn’t roll back to get momentum needed to get her legs under her. She was trapped. It was a freak accident, and not good for a bovine. The situation causes them to bloat from exhaustion and stress, and before you know it, they are dead in the night. After thousands of head I’ve been around calving, I was bound to get one of these weird situations. But with the super obese Wagyus, they could die by laying down on their own cow turd. You could lose one a day. It gave a new meaning to morbid obesity.

“So they were dying?”

“Oh yeah. They gotta keep that ground smooth. They’re just too daggone fat.”

Alderspring beeves on grass (and getting fat, I may add, but not obese) will lay down next to logs, in depressions, over badger holes, rocks and draw bottoms or hillsides. They’ll make their bed in sweet tall grass that they graze during the day. They care not where they lay (as long as it’s soft) and neither do I. To me, there is nothing in agriculture more elegant than beeves on grass. When left to their own devices on good pasture (that’s our job in husbandry), they waste not, and want not, and need no human to micromanage their existence–to create a formulated feed bunk ration or “groom” their bed.

We humans have this tendency to interfere, to reduce, to mechanize natural processes, as if we know better than something that has been functionally effective for eons…long before we showed up. The bovines called Bison have been in these Pahsimeroi plains and hills for millennia, choosing plants that best suited their wellness. Now, we’ve taken that idea one step further by reintroducing bovines in the form of our Angus beeves (descendants of wild European cows) to these native grasslands, to maximize their self-actualized wellness.

We humans have this tendency to interfere, to reduce, to mechanize natural processes, as if we know better than something that has been functionally effective for eons…long before we showed up. The bovines called Bison have been in these Pahsimeroi plains and hills for millennia, choosing plants that best suited their wellness. Now, we’ve taken that idea one step further by reintroducing bovines in the form of our Angus beeves (descendants of wild European cows) to these native grasslands, to maximize their self-actualized wellness.

As I said, we do this without “grooming”, and without: hormone implants, insecticide pour-ons, insecticide ear tags, wormers, antibiotics to enhance weight gain, manufactured chemically enhanced prepared rations, ractopamine muscle enhancers, ethanol manufacturing by products, ground paper waste for consumable roughage, sugar manufacturing by products, electrical stimulation, Jaccard tenderizing, nitro-gasification of product or a myriad of other things that separate the steer and steak from the stem…of grass.

Being in the business, we get to know too much. It’s why we can’t eat beef that’s not ours—even so called “grass-fed”, as most grass fed beef producers still use many of the above. Thanks for partnering with us on this right, and quite grassy path. Oh”¦and it’s quiet, too. Except for the low, rhythmic sound of grass being tongue wrapped and torn as our bovine harvesters move across our prairie.

Happy trails from Alderspring.

Glenn, Caryl and Girls.

Leave a Reply