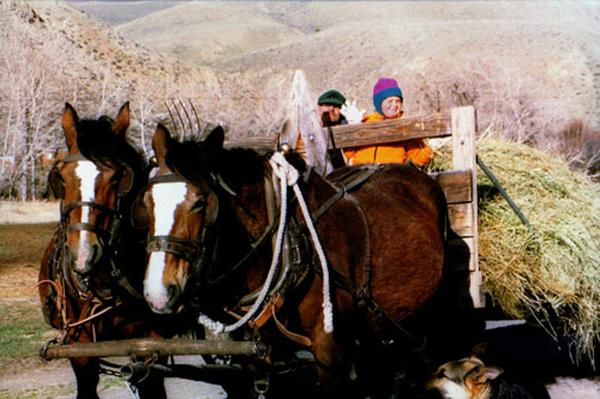

I’ll never recommend using a draft horse as a babysitter, but in a pinch, I guess they’ll have to do.

It was a leaf-blowing autumn day, and the air was thick with the fragrance of decay back on the first edition of Alderspring Ranch, in Tendoy, Idaho. Snow had already encrusted the peaks of the Continental Divide that vaunted up

just behind the ranch. The year was 1999 and we had just started feeding cows with the draft team; our fall grass was eaten off, and we reluctantly cracked open the hay pile. I had a big beautiful matched bay Belgian draft horse team named Pet and Pat that were to be my hay feeding companions and power source; I would hook them up to a wagon that I stacked several tons of hay on each day. They were the little bales that I bucked on board by hand; 80 or 90 pounds of compressed waving green summer sunshine, dried and baled in each cube.

That past summer, our ancient museum-worthy hay baler, the New Holland Hayliner, would methodically stuff the folded, cut and dried grass into bales, and neatly tie strings on each one to hold it together (this was when it worked; I would alternate between tinkering, cussing and praying when it didn’t). Almost magically, cut grass would go in the front end and rectangular bales would come out the back end, deposited like huge horse droppings scattered across the field. We gathered them and stacked them like bricks to seal out oxidation and ultraviolet damage. Then they were jealously fenced with 8 feet of wire to guard against nighttime filching from elk and deer bandits. I had pride in my stacks, ready for the windy white of winter when I would spread them out again on the same fields for our hungry cows.

Now there may be some of you out there who know the name Laura Ingalls Wilder. She wrote a series of books set in the 1800s that documented life on rural farms and prairie homesteads known as the ‘Little House’ books. I’ve read all of them to the kids. In fact, a long running series, loosely based on her books was quite a fixture on 1970s television (I remember this, and I date myself). It too, was named Little House on the Prairie; the name of one of her 6 books.

Our life was then was somewhat like the Ingall’s family; likely that’s why our kids liked our nighttime reads of the books. We lived off the land to a large degree in those days, eating and preserving food from our garden, and harvesting wild protein from elk shot and fish caught. Our livelihood was completely off the land, and as with the ranch today, our beeves only ate grass from native ranges and meadows.

So it was a curious coincidence when I brought home this team of horses. Their names were already Pet and Pat, the same names as Pa Ingall’s team of horses. Our new horses came from a ranch that functioned completely under horsepower up the valley from us. The kids took to the big beautiful horses immediately because to a kid’s mind, it was the same Pet and Pat, immortalized.

But Pat was an enigma to me. She didn’t trust me, nor I her. I guess I didn’t have what Pa Ingalls had. Her eyes betrayed her thoughts, showing white and wide whenever I worked with her. I felt like she could blow up at any time. Pat watched my quiet movements carefully as if the predator in me could suddenly erupt a la Jekyll and Hyde and attack her at any moment. And I knew that if she even construed trouble, she could explode and ruin all. A long investment of quiet from me was the only road to success with her, and that journey could take years.

Pet and Pat lived in the big corral by the creek in the autumn and winter. That way they were an easy catch, and even if it was a blizzard, I could easily find them and hitch them up for the daily feed. Off we’d go into whatever the weather brought. It might be a fall whiteout that squalls from the highline of the Divide would bring. Then, on the way back it could be brilliant sunshine that melts the new snow off their backs. You see, fall weather could change appearance as fast as a teenage girl in the hour before a date.

But the horses were used to such fickle weather, and were stoic despite what weather would dish out. The mares would hair up with luxuriant fall coats like Icelandic ponies, and their faces would be covered with long guard hairs that kept their eyes and noses from freezing. Billows of steam would rise off their backs in the chill air as their backs heaved with deep breaths from pulling tons of hay across bumpy fields, but I felt as though they relished their work, especially on cold days, as they leaned hard into their traces with not a word from my lips or snap of the lines.

It’s actually the tiniest squeak from lips that gets them going. It’s like the sound a mouse makes, if you’ve ever heard it. The Hollywood Western stereotype of vigorously snapping the lines or cracking a whip and yelling “Haw!†is absolute nonsense.

The old teamster, Lloyd Clark (this is where the word teamster actually comes from, by the way; it wasn’t created by a national union of workers that try to woo presidential candidates to their agenda) taught me most of what I know about the big teams. He told me “You don’t ever want to shout at them, Honey. Fact is, you should always give them the quietest peep from your lips. That way, they’re always listening, ears fixed on you and only you. You want them to focus on only you.â€

Lloyd had eyes that cut through the noise and clamor of competing thoughts, just like the squeak he spoke of. “There could be all the noise of talking, and machinery and all else around them, but they shouldn’t go until you give them your go.†He called all of us men on his ranch “Honey†by the way. It kept things in order. He was senior by far to us all, in both years and experience.

Our kids were too young to go feeding with the horses back then. Melanie, the oldest, was only 6, and wasn’t strong enough to hold on to the thick heavy leather lines that ran through a series of brass loops to the bits, fit to each of the horses. Even if not driving, it was unsafe for a little kid. They could fall off, or startle the horses while I got off to open a pasture gate. My imagination could go wild with what may happen in those circumstances. Screaming kid bouncing off an airborne hay wagon with wide-eyed horses bolting off for barbed wire…

No. Not going to happen. So I’d be alone, except for Maggie, my trusty Australian Shepherd. In quiet we’d go, Pet and Pat’s ears screwed backwards, awaiting commands from me. Pet was always responsive, but Pat, well, she had her own agenda about me most days, and just followed Pet’s lead.

The day had dawned like many days on Alderspring. Most of our weather is sunny, even in the fall and winter. There may be thick clouds in the mountains, dumping snow all around us, but we usually stay high and dry from the sun window that forms above the valley unless a squall spilled down from the upper elevations. Today looked like it would stay sunny and by late morning, the thermometer rose to over 50 degrees. Four kids and Caryl bailed out of the tiny house we called home; already cabin fever was setting in, as we were a little tight in our humble abode. The grass on our small yard next to the garden felt good between their bare toes in the high altitude mountain sunshine.

We didn’t worry much about the kids this time of year. The rattlesnakes and bears were all in hibernation, the creek was just a trickle, and it was a little chilly, so they wouldn’t go far. The county road was an equivalent of miles away for little kid feet, and there was no traffic, and zero people. There was just a little bit of brush and trees on our sprawling western landscape; to them it was a Little House on a big Prairie.

Caryl and I finished a cup of morning coffee on the steps in the sun. Then I headed out to check cattle and she headed in with the baby to clean up from breakfast. The three older kids, ages 6 to 2, stayed in the sun playing in the yard.

Fifteen minutes, I headed over to the corrals to catch, halter and harness Pet and Pat for our feeding ritual for the day.

As I walked up, Pet was ranging around the big corral. She just finished a back scratching roll in the sunshine as evidenced by the hay that still stuck to her back. But Pat stood curiously still, her head fixed high and awkwardly above the feed bunk. She seemed unsettled in her eye, but wouldn’t move. I couldn’t see her feet; they were behind bales of hay she had been working on through the rubbed-smooth wooden feeding bars across the manger that faced me.

I lifted the wrought iron latch on the massive wooden corral gate. It creaked loudly of wood on ancient wood as it swung open; I caught it before it would open all the way, and swung it shut behind me with a resounding clank on the iron latch. I think it was that sound that startled Linnaea. Her two year old voice started crying, I think, when she realized she was without sisters. I froze when I spotted her.

She wasn’t quite alone; she was with Pat. Pat, that horse who I had trouble connecting with. Pat with the unsettled and untrusting eye. Linnaea was sitting, little pink panted butt down in the corral hay, and had evidently been playing quite contentedly between Pat’s two muscled front legs. They were like small tree trunks attached to 1 ton of draft horse power. Pat wasn’t one of the fat and slick Clydesdale horses you see in the Tournament of Roses Parade. She was well conditioned and agile.Those hoofed feet were almost the size of dinner plates, hardened by a season of treading on the volcanic soils of her summer pasture.

Linnaea slipped a little further in between Pat’s feet and stood, steadied by the solid legs of Pat, with one hand on each of the fronts and her head not reaching Pat’s body above her. Now that I had come on the scene, Pat was getting jumpy, and moved nervously in place but keeping her front feet planted.

Then Pat moved.

Slowly, she lifted one front leg, and gently scooted Linnaea toward me. Linnaea, 2 years old and still not perfectly steady on feet, waddled toward me from between the mare’s legs, barefoot in pink across the hay. Now free, Pat trotted off, tail up, flag-like, waving in the air, with nostrils flared, as proud as a babysitter could be, across the corral where she stood next to Pet and watched me scoop up the now quiet Linnaea.

I’ll admit when I write this story my heart catches a little and I feel again the adrenaline pumping fear I felt that day. The kid was two, for crying out loud, and neither Caryl nor I ever thought she would leave the yard or her sisters (by the following summer I had put up a fence for my wander-lust offspring; this same kid travelled alone to New Zealand when she was 18).

But I am a thankful dad as well. In all our years of mixing horses and kids, I never saw a horse be mean to a little kid, although plenty of our horses were not so patient with young men or me.

Over the seasons, Pat came around to trust a grown-up human, and that privileged one was me. She and I worked closely together for years and became partners, deeply connected in that sort of way that you can with a horse once you find common ground in the work at hand. As with all of our horses, we kept her until she died. It was several years later when I found her in the pasture; her heart finally failed despite the fact that she was still doing some light work with me. I crumpled to my knees and cried into the dust.

I still miss her.

I often ponder about why we chose this life. There is life and beauty and joy, but there are also hard things: moisture that doesn’t come, machinery that won’t work, and, hardest of all, animals that we love die. This sometimes heart rending life we carve out on this remote landscape was borne out of a mutual decision Caryl and I made 25 years ago. We’ve lived in and around cities all across America, almost always involved in some form of agriculture or ecological conservation work. Although we both had pretty rural roots, we explored urban life to a point where we completely understand why folks choose such settings. Perhaps it’s work, culture, exposure to the arts, or all three. We miss some of those things.

But we both had a vision of connecting people to the land and a living soil underfoot. Connections made not only in the stories or pictures that we post on social media, or in contacts that we make at farmer’s markets or store samplings, but the connection of agricultural wellness and the wellness of the people we served. Because we knew, or maybe at that point we just intuitively felt, that there was wellness to be had for all the partakers of plants grown and stewarded on wild and pristine landscapes, even before science and research started to uncover the incredible nutrient density and diversity found in such places.

I’m not talking about dead soils that get ripped by plow and disc, left open to oxidation each year in the planting of annual crops, the living soil functions now replaced with chemical amendments. I’m talking about soil that has that living part to it that you can smell and feel. I smelled it on our wild range last week as I grabbed several handfuls of the rich soil. It crumbled in my hand into uneven fragments of root, detritus and fungi. It carried with it the fragrance of life and decay at the same time. It’s those two components that allow wild plants a “whole foods†advantage over dead, chemically subsidized dirt. From living soil comes nutrient dense grass, and from such living grass comes animal protein with great wellness attached to it.

It has been worth sticking with it for these 24 years. Friends and family were looking at us askance, and some still do, with our sometimes austere and sleepless existence that we intentionally chose. But living on and in the landscape is critically important to connect the dots of wild wellness that we serve up to you as protein. We have now become part of the land, and life on it. Thanks for joining with us.

Happy Trails.

Glenn, Caryl, Cowboys and Girls.

Leave a Reply