In retrospect, I know now that it was a love affair. Her name was Missy, and I believe it was mutual. I didn’t even try to keep it a secret from Caryl. I knew that she figured it out early in my forays into distant rangelands with the then nineteen-year-old Missy. We had been discovered in our not-so-secret relationship. Interestingly, I actually believe my wife understood it, as she had been in relationships like this as well.

I was smitten.

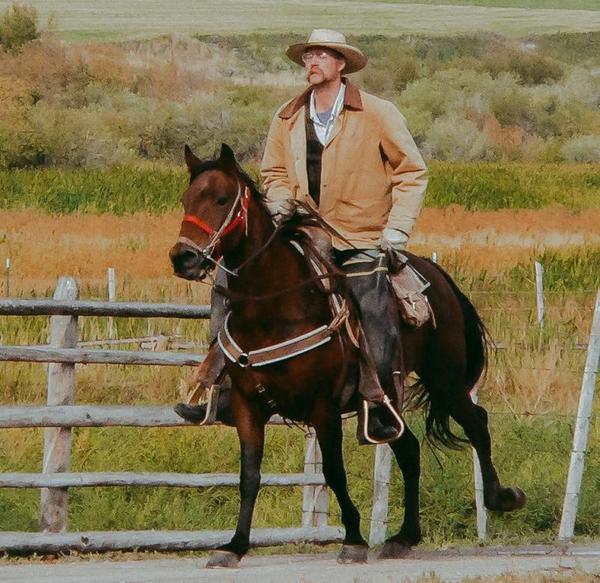

“‹”‹”‹”‹”‹”‹”‹It wasn’t her beauty that wooed me first, although it was captivating when her long black hair tousled in the fresh alpine winds on our forays together in the high country. And then there was the way she moved. Her smooth and sashaying gait was unlike anything I had experienced; even her ears begged attention, especially the way they indicated her rapt fixation to whatever it was she was looking at. There were countless times we were alone for days at a time, exploring wild landscapes, and seeing vistas of endless peaks marching to the horizon, blanketed by forests and capped by snow. We explored and learned a new country together, and those first few summers on the Hat Creek ranges will always be embossed clearly in the pages of my mind.

On this particularly lovely midsummer day, we happily moved cows across the high forests above Park Creek. I pressed my un-spurred heels ever so lightly into Missy’s sides; it was so subtle that it was nearly telepathic. It was all she needed to move out. Usually it was just a little shift in body position, in a center of gravity on my part; the slightest change would send her quickly forward. She had never been a tame horse, but she certainly was responsive and astutely tuned in to me, now an imperfect extension of her.

“‹”‹”‹”‹”‹”‹”‹

And she was mine. Not only by ownership, but by relationship.

Sure, others rode her upon occasion, when she was fresh and one of the hands needed a horse not ridden for a few days. But she and I developed a special connection over the years, despite the fact that she didn’t look like the stereotypical cow horse. She never got used to a rope, and wouldn’t tolerate such nonsense. There would be no loops thrown of lariat from her. She was a purebred Morgan, not the quarter horse that most cowboys rode, at least in our region of the West.

After she and I got well acquainted, often we would take lunch in a high meadow after a full morning of cow moving or creek riding. I’d pick a verdant grassland, full of wildflowers and lush forage. I would open up my saddlebags, and pull my usual lunch out; a block of cheese, a can of herring or jerky, and an apple. A note on that apple: it wasn’t any such store bought apple if it was later in the season; it was one or two picked from our little tree in our front yard. I have no idea what kind they were, likely some kind of ancient and lost heirloom variety. All I knew was that they were hard, crunchy and tart. I think they were made for the saddlebag; their red flesh rarely bruised.

I think a horseman, a cowboy planted those.

I dropped her reins on the ground. And she stood. She was the most respectful ground tying horse I have to this day been around, and when those reins were dropped, hell and high water couldn’t move her.

But it was lunchtime for both of us. I pulled her headstall off, removing the bit from her mouth, and all semblance of control from her head. If it was hot, I pulled her saddle, and she would quickly find a piece of particularly even textured grass, and happily roll the sweat stains off of her. She was free as a mustang; there was nothing that could keep her now; she was free to run, and there were often ten to twenty miles between us and a fence. It would be a long walk if she got away, not to mention the fact that she could throw in with little mob of feral horses that ran our remote ranges.

There were others who tried this. I remember when Joe, one of our second year riders tried to leave her free over lunchtime. Six miles later down steep canyons and rocky trails, dripping sweat and gasping for thin mountain air, he caught up to her at the first barbed wire fence. Missy hadn’t broken a sweat yet. By dumb luck, the gate was closed where the mare was reluctantly waiting for her rider. If it had been open, Joe would have likely had to walk over 25 miles before catching up to her back at the ranch.

And that’s embarrassing, not to mention a flat waste of time, according to the boss man (me).

Missy started eating after I let her go; immediately after the roll. It was her favorite thing to do, and she launched right into her wild green salad with abandon. I reclined in the shade of a pine tree, enjoying my simple sustenance.

And more often than not, I drifted off in a 15 minute siesta, lulled to sleep by the sound of Missy mowing down the sweet green. Occasionally, she’d wake me early, when she decided that the best grazing was right by my head. But for the most part, I drifted off uninterrupted (there’s no nicer place for a nap than in the shade of a pine tree caressed by the thick and fragrant breeze of pristine mountain air).

And she would be waiting for me.

I gathered up saddle and headstall, and she knew that it was back to work. I easily swung leg over her shorter-than-quarter horse back, and we were off at a brisk trot. Unlike many geldings I have ridden, this mare had grit. She could go 45 miles in a day through rough country given the chance, and though exhausted, would push on undeterred, and could keep her trot going for those last miles.

I remember one day of trotting the entire day that still makes me smile and feel bad at the same time. But there was a sort of poetic justice to it all, akin to a balance of karma, because I had to go through the same rite of passage in my young twenty-something day under the twinkling eye of several salt-of-the-earth cowboy codgers.

Besides, there was this simple physiological fact: the young rear end of a 20 year old up-and-coming range rider had a great capacity to be worn raw and subsequently heal.

The owner of said seat: Tim, from Buffalo, New York. He was new to this riding horseback thing. He was aboard Gus, and we had just moved the entire cowherd up on to the higher US Forest Service lands on the Hat Creek Range. It had been a terrifically long day, but thankfully, we still had summer solstice daylight to get back to the Salmon River, another 12 miles or so down canyon.

But it was late, and we proceeded to trot it out. For those of you who don’t know, trotting is the second gear of horse above walking; it is in no way a run, but will cover rangeland real estate in half the time of a walk. The trick of trotting is more for rider than horse. Just simply placing your hind quarters on horse doesn’t work, and will tend to addle your brain in constant jolting, and undo any part of your own hide that is undergoing friction in the bump and jostle.

To survive through the trot, one has to either create a body rhythm in cadence with the equine one (called posting, used most commonly in English horsemanship), or just keep a seat and body that is an extension of that of the horse. Simply going along for the ride as in a car will not do.

Well, we had been trotting nearly all day, and Gus, stereotypical quarter horse as he was, could be a pretty abrupt and bumpy trotter. Missy on the other hand, was smooth as silk sliding over a baby’s bottom. I was feeling pretty good. What I lacked in my own trot technique, Missy covered up with her ambling and comfortable gait.

Tim kept a straight face when we made eye contact, but during the last few miles, I could detect wincing from the pain he was enduring. I just kept grinning at him. Every now and again, he caught my happy eye. Problem was, I couldn’t tell if he was angry with me, impressed with my comfort and happiness, or both.

Regardless, I knew Tim was a keeper after that day. We covered nearly 35 miles in canyon and rock, and I knew he would make the grade. I also knew he had trouble sitting down for a few days.

Tim not only survived, but thrived. He stayed on for four years. We would laugh about that day for years thereafter.

But today, I was alone, as Missy and I picked our way down the narrow trail through the aspen forests along the bubble of Park Creek. It was one of the remotest places in the 70 square miles of the place we call Hat Creek. Trails are narrow and ghostlike, disappearing into rockslides or brushy thickets, sidehills are steep, and only elk, deer and mountain lions call it home.

I was about a mile above the abandoned Taylor Ranch, an extremely remote hardscrabble ranch homesteaded around 1910 by an old vestige of the Civil War era. From the looks of the rock and brush around his tiny log shack, it was a brutally tough existence. He ended up dying in his bunk in the winter of ’17, his vacant shell of a body discovered by a few acquaintances who rode in the 25 miles from May, Idaho to check on his whereabouts after he never showed up at the Mercantile for his springtime supply foray.

They buried him in the cobble behind his humble shack; the rough shelter still stands, bunk, woodstove and partial larder still intact in the glass jars he kept them in. I pay homage to Taylor’s memory and the fortitudinous nature that he represented whenever I ride by. I’ll step off my mount, lead horse to water while grabbing a breather, and visit the cabin and reflect that few today would embark on such a difficult prospect as he had.

The mare and I continued to pick our way through the aspens and broke out into the green grass and floral display of a creek side meadow. Missy’s telltale ears perked up, erect, and she halted her decisive trot abruptly.

She exhaled enough to manage a quiet snort, head, ears pointing like a bird dog on a ruffed grouse. Following her gaze was easy: a large boar black bear, on his hind legs. His head wended its way around in the air, trying to wind us, and make scent sense out of us: friend or foe?

He was just 50 feet away; we had surprised him on his chokecherry binge. His mouth, teeth and lips were deep red from gorging on the abundant berry mast alongside the creek bottom. I had been seeing his scat for several miles now, more cherry pits than poop.

Missy simply stood ground, waiting for any signal that I may give. She would run if I told her to, even if by only by a thought; she was a coiled spring underneath me. But both of us, for now, were transfixed in the moment.

I think the bear was too. He simply stood there, staring, licking lips. And then, after several minutes, he dropped down to all fours, and continued on his business downstream. We were just boring horse and human, after all. And there were cherries to imbibe and the work of winter fat to lay down.

Missy and I resumed our downstream foray as well, on the other side of the thickets of willow, birch, aspen and cherry that would lead us 4 more miles to another more pronounced trail, that of Little Hat, that would lead us in the gathering darkness several more miles back to our gooseneck trailer and truck that awaited us. It would be our wheeled conveyance for the final part of this day’s journey. Finally, sometime after midnight, we would be home.

Actually, as I write this, I’m realizing that it is all home. We had been adopted by the landscape, this wild country, and the wild inhabitants on it. It no longer felt as though we were aliens in a foreign land. We have become part of and parcel to the land, and the ecosystem on which we live and roam. To steward this extended home is all honor, especially when we can share some of the literal fat of the land with the likes of you.

Happy Trails.

Glenn, Caryl, Girls and Cowhands at Alderspring

Natalie

Wonderful story. Wonderful horse. Wonderful partnership.

Thinking about your expansive ranch, I wondered if, over the years, you ever got lost?

Yesterday I watched the end of a pony club jumping competition, where they were awarding horses and riders for their efforts. At the very end, six or eight riders dismounted and did a sack race, riders wearing sacks and horses happily walking beside them. The horses were far more graceful than the sack-adorned riders, especially as several of them tumbled to the ground. But it, too, seemed like a wonderful partnership.

Judy Summerville

what a beaytiful story! I was one of those kids who saved up their work money to buy a horse.