Roscoe Hamilton trotted his horse, heading for sunset, and home. He had just settled his shorthorn cattle on thick, deep and undulating grass covering the big sloping bar that tilted down toward the Pahsimeroi River. The grass reached up to his stirrups, and he could hear it swishing by as he headed across the prairie. He was almost home now, and he could settle in and check on his wife and young children in the log home they had constructed, just off the bar ground, in the moist river bottoms.

As he crested the final wave of Pahsimeroi prairie, he pulled up his gelding to survey the scene of the valley below him. Smoke curled up from the chimney of his homestead, and from a few others that dotted the expanse of green as the valley spread downstream to its junction with the Salmon River. Like him, all of the residents were new arrivals in the broad valley sward in this spring of 1879; although homestead life was tough for the takers of this new country, it was the grass that kept them.

It was the best grass they had ever seen. The few homesteader arrivals had come from everywhere and hailed from places like Europe (several were from Italy) and the colonized and fairly well developed east coast. These were often Civil War veterans from the battle-scarred South. All of them had found paradise in this particular valley; no other place quite captivated their cattle raising hearts. Here was a valley with unending deep green, and no brush. In addition, it had little wind, being protected by a formidable wall of 10,000 foot rock and snow strewn peaks. These same mountains bore adequate timber for building infrastructure like homes, barns and fences, and best of all, they captured nearly all the moisture that fell over the winter in the snow catching high elevations.

That meant there was little snow cover on the valley floor, and the abundant grass was grazeable for the entire cold season. Open water was always available along the warm spring fed Pahsimeroi River. The combination of these ideal factors meant no one fed hay; there was plenty of graze for the entire year. If ever there was a cattle paradise, this was it, and Roscoe knew it.

Even the name was said to be an obscure Shoshoni word describing “this land of tall grass.”

The shadows cast by the setting yellow ball to the west deepened the texture of the prairie, rendering the volcanic soil substrate below invisible. It was time to walk instead of trot. The risk was too great to have his gelding place a foot into an obscured badger hole. He touched heels to his bay, and moved out.

He took only a few steps before he stopped again, spotting a shape in the graminoid depths. Roscoe slipped off, and reached down into the black for more black; it was a cowboy hat, beaver felt, worn and a little tattered. A crusted sweat stained ring tinged the body of the hat more brown than black. It had been here for a while, perhaps even lasting though the winter, Roscoe thought.

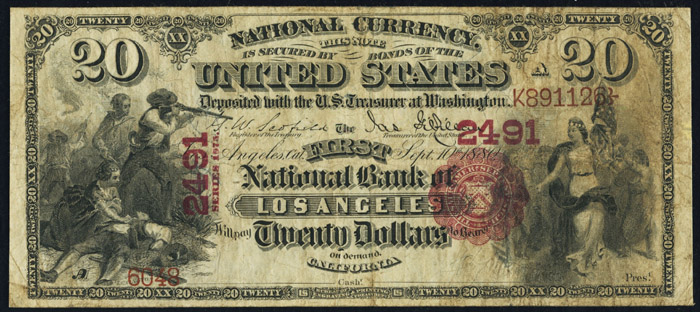

He fingered the hat, and looked inside at the worn leather band. A sliver of green protruded from behind it, snug against the felt of the beaver fur. He carefully edged it out with his thumb and index finger. It was a twenty dollar bill. It was enough money to buy a good saddle horse.

Roscoe placed it in his pocket, and, gathering the hat, slipped a foot into his stirrup and rode in to dinner. The sun was setting as he rode into his dooryard on the Hamilton Ranch.

Knowing that the mercantile and the sprawling Salmon River Ranch he owned would operate without him, Colonel George Laird Shoup, formerly of the Third Colorado Calvary, was mustering troops again.

This time, it was from his newly adopted homeland of the Lemhi Valley, in the Idaho Territory. It was August of 1877, and the battle of the Big Hole of Montana had been fought only days ago.

Calvary forces had failed to halt Chief Joseph and his band of 700 Nez Perce in a short altercation in the broad Big Hole Valley, and their proximity had created fear and consternation by settlers in the nearby Idaho Lemhi Valley. The Chief and his tribal community, bound and determined to hunt buffalo in their traditional hunting grounds, had been dodging the Calvary since slipping away from them in their home territory of Northern Idaho. The US Government insisted that Joseph and his compatriots stay on reservation lands appointed to them, and the Army’s Calvary was sent to stop them and return them to their northern Idaho reservation.

Chief Joseph had become a man on a mission, driven by more than the US Army. What had started out as a smaller vision of a final buffalo hunt had become a mission of principle, a quest to find freedom, and as such, an allowance to continue the nomadic tradition that coursed through his veins. It had been their way for hundreds of years, and it was their life.

He didn’t want violence, but by fleeing he and his people had become fugitives. The headed over the pass from Montana’s Big Hole Valley into the narrower Lemhi Valley in Idaho. A courier rider had brought news to Salmon that after a brief skirmish near the headwaters of the Lemhi, the band of Nez Perce had crossed the pass south into the broad Birch Creek Valley. There, warriors from the Chief’s band were engaged in a skirmish with a train of four freight wagons heading toward Salmon from Salt Lake City.

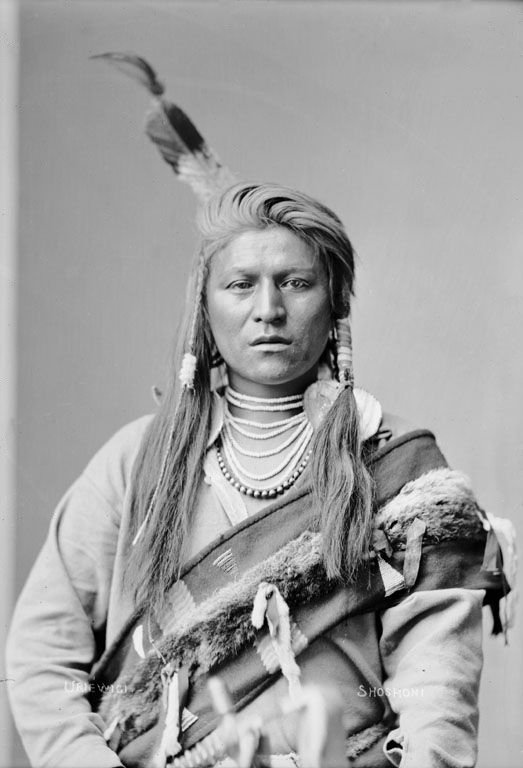

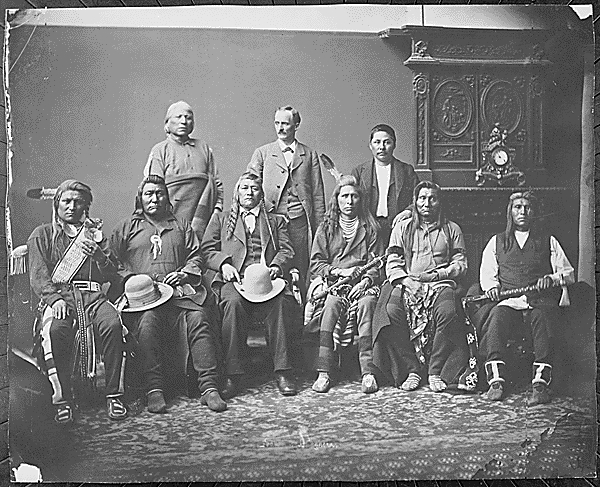

Colonel Shoup, though officially retired from Calvary duty, was a recent appointee to the Idaho Territorial Legislature. As such, he was the local in charge of altercations with Native Peoples. He put together a posse of young men to investigate the alleged freighter attack. There were several young white men from Salmon City, along with an unusual addition: Chief Tendoy of the Lemhi band of Shoshoni, along with several of his braves rode with the Colonel. It was nearly 100 miles of trail and two long days horseback to the scene of the reported attack.

The Colonel often sought out the attendance of Indians, and welcomed their participation. For whatever reason, he appeared to be unprejudiced about the natives.

At the end of the first day’s trek, the men settled down to camp in the high Lemhi, near the present town of Leadore. There were several ranches in the area, and the posse picked one to camp on, where they could feed and water their horses.

After posting a sentry, and cooking some victuals over the fire, the men spread their bedrolls in the willows in the gathering darkness of the evening. Their sleep was punctuated by an abrupt start. Their posted sentry called out a shrill challenge, as the thunder of approaching hooves echoed through the bottoms along the river where their bedrolls were made.

Shoup’s entourage jumped awake, grabbing rifles at the ready, pointing them into the darkness as the horses approached, now more quietly after the sentry’s call.

“Halt! Who goes there?!,” The sentry called again.

A voice quietly called back through the tangle of willows in broken English: “Jack Tendoy, son of Chief Tendoy.”

Twenty-year old Jack Tendoy then quietly rode into the camp where he met Colonel Shoup, and his father, Chief Tendoy. There, he presented his recovered booty. It was over twenty horses he had singlehandedly stolen back from the Nez Perce by cover of darkness the night before. They were all horses from ranches in the upper Lemhi that he intended to bring back to their rightful owners, in the very area that they camped in.

It was not the first testament to how highly skilled the Lemhi Shoshoni were at horsemanship. Seventy-two years previous to this reunion at night along the waters of the Lemhi, Jack’s great uncle, Cameahwaite (and sister of Sacajewea) greeted Lewis and Clark as they first crossed the great divide. Lewis and Clark were notably impressed at the horsemanship of the tribe at that time.

Needless to say, Jack made quite an impression on Colonel Shoup that day, and Shoup would remember him long into the future.

The next day, the entourage continued on to find what they hoped wasn’t true. All four wagons were ransacked and burned, and the four drivers were shot and killed on Birch Creek. A monument to the event stands on the remote site to this day, along modern day state highway 28.

It was a tumultuous time for the native peoples of the West. In just a few short years, cultures and peoples that had existed in an uneasy balance for millennia were forced into upheaval. Certainly, there were enemy tribes throughout the Americas, and bloody battles were often the result. But never before in their history had such a rapid and catastrophic change occured. Decimation and dispersal was nearly complete by the agents of disease and warfare.

The flight of the Nez Perce ended with their capture near the Canadian border in Montana the winter of 1877. In the summer of 1878, the Bannack Uprising broke out. Again, US attempts at subjugation of the Bannack and Paiute tribes of Southern Idaho and Northern Nevada resulted in fighting that brought a band of Bannack Indians to the small town of Mackay, Idaho, about an hour’s drive from Alderspring Ranch.

Again, it was over a freight wagon, this one bound for the Shoup Mercantile of Challis, Idaho. It was another one of Colonel Shoup’s dry goods stores, co-owned by a Captain Jesse McCaleb. The Civil War veteran and Shoup had become friends, and got into business together.

It just so happened that this particular wagon was well equipped with just one thing: guns and ammunition. And it appeared that the Bannack knew it. Because of the unique cargo, a party of 12 riders packing rifles and two wagon men accompanied the freighter as it lurched its way into the narrows, at the foot of the Lost River Range and the present site of Mackay Dam.

There, they made camp, and a wending smoke from their fires partially blocked the view to the rocky heights that soared to the sky above them. An 11,600 foot peak with a massive summit block loomed a mile straight up from narrows. It would be named Mt McCaleb after the man in command of the small group in the camp below, because of what would happen on the next fateful day.

Over 200 Bannack attacked the wagon on the morning of August 12 at the narrows, and 14 men successfully held them off over two days of fighting, due to their rocky narrows location and abundant ammunition and weapons found in the wagon they defended.

But Captain Jesse McCaleb stretched his bald head one too many times above the rock he hid behind, and was killed instantly.

A rider was dispatched immediately with the news of the Bannack making their way toward Challis and the Pahsimeroi. Shoup received the devastating news that his partner was dead, and immediately summoned the best rider and most dependable man he knew: Jack Tendoy.

He sent young Jack, now 21, on an express warning trip to let the settlers know in the Pahsimeroi that there could be trouble, and to be ready. He pressed a twenty-dollar bill into the young Shoshoni’s hand just before he galloped up the Salmon River Canyon to the next valley. It was a distance of 38 miles, over canyon and rock. At gallop and lope, it was a difficult trip on broken and stony trails, but Shoup needed to get warning to the settlers on ranches in the remote Pahsimeroi Valley that trouble could be imminent.

Jack made the river canyon in good shape; by the next morning, he was venturing up the through the low Pahsimeroi letting residents know what was happening. He had not gotten very far when he was jumped by a small band of Bannack, likely on a scouting mission.

They pursued Jack down valley and allegedly shot at him, as he galloped in retreat, outnumbered and alone. In the terrific chase down the valley, Jack lost his hat.

And his twenty dollars, which he secured in the hatband.

He quickly rode, defeated, bringing news that the Bannack had already arrived back to Colonel Shoup in Salmon City, hatless. He told all that would listen the story of being run off, outnumbered, and outgunned, and that the Bannack had already reached the broad Pahsimeroi Valley.

Most white people of the day had little trust for Indians, and despite Shoup’s selection of Jack, trusted little of what he had to say. They simply didn’t believe him. He was an Indian, after all. He just pocketed the money, they said, and probably never even did the Colonel’s bidding to ride up there. He likely spent in on liquor, they said.

But Shoup wasn’t so sure.

And then, after a year or so passed, like water that flows down the Salmon River, word slowly trickled down the canyon from the Pahsimeroi to Salmon. It was at first a little obscure; and then a homesteader’s name became connected with it. One Roscoe Hamilton had found a twenty dollar bill in a black hat, and wanted to return it to its rightful owner.

And Colonel George Laird Shoup knew who it belonged to, and that his story was true, and that this Indian told no lie.

And I believe it was how a young man, a little-known native by the name of Mr. Jack Tendoy, of Lemhi Agency, Idaho, was asked to represent an entire people, a tribe, and be transported by rail to attend treaty signings in Washington DC, in 1890, along with his father, Chief Tendoy. And named one of the administrators of the Lemhi Agency in 1897. It was the set-aside reservation lands in the heart of the Lemhi Shoshoni’s home territory, near Tendoy and Lemhi, Idaho.

Jack died an untimely death shortly after in Spencer, Idaho. He was just 40 years old, and the favored son of his father, Chief Tendoy. The cause of death is obscure; word was that the Bannack and Nez Perce finally caught up with him and killed him in an ambush in revenge for his cooperation with the settlers.

As I write this, I can gaze out of my office window to the big rocky gravel bars that stretch out of Lawson Creek at the foot of the mountains. These are alluvial fans that connect the steeply tilting upright rocky buttresses of the peaks with the flat of the broad Pahsimeroi Valley. There is one bar, called the John Smith Bar, that spreads out for several miles, fanlike under a rocky canyon below John Smith springs. Below that sagebrush bar is a big log house and a ranch, with numerous outbuildings, some of which are comprised of old timbers of Douglas-fir, weathered and gray with age.

Their corner notches have signature axe-marks, handily cut with a double-bit, painstakingly whetted with file and stone, wielded by one Roscoe Hamilton, homesteader and first rancher in these parts.

Then, as my eyes wander across the broad vista to the West, into the setting sun across those bars, with a little imagination, I can see in my mind’s eye a sea of grasses instead of sage, coursing with green waves in an evening breeze. They are lit emerald by the setting light of early evening. Then, I suddenly spy a band of several native horsemen, their multicolored mounts war bridled, swiftly galloping, sweating, blowing in hot pursuit of one rider. They don’t gain on him. His mount and ride is better than theirs. His fluid form draws away from them, ghostlike, in a light plume of volcanic dust. He is the superior horseman.

He is of Lemhi Shoshoni blood and leaves Bannack to eat what hangs in the air. And that wispy gray particulate settles on his black hat, blown off in the race, now tucked deep inside the velvet of thick green.

Happy Trails!

Glenn, Caryl, girls and cowhands from Alderspring.

For 26 years, handcrafting unparalleled flavor and wellness while regenerating wild landscapes. Wild Wellness Delivered.

Postscripts:

- Colonel George L. Shoup became the first Governor of Idaho in 1890 upon declaration of Statehood; he then became a US Senator shortly afterwards. The hamlet of Shoup on the Salmon River is named after him; the cattle ranch he founded and ran for several years just upstream from Salmon is still ranched for the most part.

- Alderspring’s first location, in the Lemhi Valley, was where Chief Tendoy lived, and eventually was buried, as was his son Jack. Many descendants of Tendoy visited the ranch while Caryl and I lived there. The Alders, who we originally purchased the ranch from in 1993, were close friends with many of the Tendoys, and would come to trade goods with the Alders. There were many afternoons where I would walk by the Alder’s home on the ranch to note up to six Shoshoni in their home, happily seated and sharing tobacco with the Alders. To my observation, elk ivory, actual ivory extracted from the jaws of wild elk that Ron and Frances harvested was the most common currency in their trades. Frances always kept a box of the highly sought after gems in her bedroom.

- Roscoe Hamilton’s abode still stands just several miles below today’s Alderspring, adjacent to the current Bowles ranch holdings. He is the grandfather of 88 year old Bud Hamilton, Korean War vet, and current resident of Challis, Idaho. Bud cowboyed for a good many years on the Hat Creek Allotment, currently run by us on Alderspring.

- Jim Martiny, longtime resident and cowboy from May, Idaho, provided many of the details about the hat story, as well as the condition of the valley at settlement. Jim’s grandparents homesteaded the valley in 1889. Jim related that at that time, there was “no sagebrush, only grass up to your horse’s belly.”

Evelyn M Marshall

I like the set up of your newsletter.

Please advise if in the future, you may be offering a whole chicken with all the internal organs such as heart, liver and giblets (of course cleaned) without the feet. Thank you.

Daniel Jardien du Maurier

Terrific quote at the top of the newsletter! Have you read ‘Cows Save the Planet’ by Judith Schwartz?

Erick M

Another great read!

What is/was the changing factor from a grass valley to sage, over grazing?