Dear Friends and Partners

My coal-black mare, Bobbi, tripped on her feet for the last time with me on her back. She had a good excuse, to be sure: it was quite dark. I quietly pulled her up, and swung my leg over to dismount on her uphill side. The steepness of the hill made getting off as easy as sliding my foot back on to the rocky ground, as it was nearly the same height on that side as my stirrup.

Yep. It was steep alright. And it was a long ways down to the bottom of Pig Creek canyon. And sure, there was this multitude—actually, several millennia– of elk, bighorn sheep, bison and cattle trails permanently etched into the mountainside on which we rode. The tiny trails were called terrasets, and they were permanent signatures on the land of countless beasts that trod before. Each was a foot wide terrace on the hill.

But it was the numerous unseen rocks, hiding beneath the sage that would trip us up. One misstep to the downhill side would send us careening ass over teakettle down to the bottom of the canyon.

One problem was that I had that happen on what used to be my regular ride, Ginger. We were on a trail like this when she tripped to the side, then careened, thankfully losing me from saddle and stirrups after the first roll over my body. But she never did stop until piling up in the brush at the base of the hill, motionless, at least until I got there, hundreds of feet down. Long story short, she made it, and I made it. Both of our legs were badly bruised—no, hers were more like mangled– but after several months of healing we rode on for thousands of miles together for subsequent years afterwards. She’s still around, happily enjoying a well-earned retirement.

So Bobbi and I both walked where I would have ridden in daylight. She mostly lacked experience, is all. She was only 6, and barely had placed a foot in these mountains. I peered through the black at the starlight illuminated shapes of 22 head of black Angus beeves that Melanie and I were trailing down the 10 miles from the headwaters of Moose Creek to the corrals at Little Hat Creek.

There, 9 miles of sinuous dirt two track connected the wilderness with civilization—a paved road—and eventually, Alderspring Headquarters.

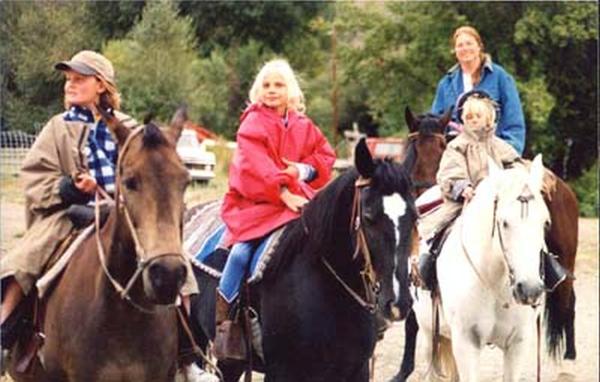

They were finish beeves—one hundred percent grass fed, certified organic 2 year olds brought to fattening on the wild and pristine landscapes of the Salmon River Mountains. Daughters Melanie and Linnaea had sorted them from the 320 beeves running on the range this year near Moose Creek cow camp, and I had arrived with saddle and horse to help Melanie trail them out to harvest, and market on the internet over the next couple of weeks.

I could hear Melanie’s voice in the canyon below me, talking quietly to the small bunch of cattle as we trundled them along down canyon to the confluence of Pig Creek and Little Hat Creek. We had about 7 miles behind us, and despite brush, creek, canyon and rock, we still had them all.

She was aboard Goldy, a little gritty buckskin mare that had launched many a rider off. She was given to us, no good to her former owner. She was cold backed, that was for sure, and was prone to buck if things weren’t to her liking. But it turns out that some of these bitchy mares that occasionally ditch a rider turn out to be the best for us.

Because once they feel partnership in purpose, they will literally die for you. These kind of horses are all business, and don’t put up with any riding in circles nonsense. They’ll actually nip at recalcitrant bovines to get along, and won’t tolerate anything they perceive as not related to the task at hand.

They are often covered by bitemarks, given in retaliation from other horses they try to bend to their will.

I recalled April, long time Alderspring black Morgan-Arab mare that would simply bite the leg of any human riding on another horse alongside, trying to pass while I rode her (she seemed to have a particular penchant for a Levis-covered thigh of a government employee). She often grabbed a piece of my flesh simply for tightening the saddle cinch.

She required a large berth of personal space, as on several occasions, I found myself mounted in the middle of a kicking, bucking and biting match between competitive mares.

On this particular night in Pig, I now could hear Goldy and Melanie clatter up the canyon wall, jumping from terreset to trail, over rock and ridge, Melanie egging her forward, now above me on the wall, grabbing a stray heifer.

The light of Jupiter and the incandescent orb of the Milky Way provided just enough light to spot the moving shadows (Melanie, Goldy and cattle) and separate them from the non-moving ones (rocks and brush).

I spoke up to Melanie. “I got off—this Bobbi is just unstable enough on her feet that she’s gonna slip down this mountain.”

“It’s OK. This mare’s got good feet under her. And pays attention.”

She was right. My mare, Bobbi, was often too busy thinking about herself or where Goldy was, and she would often forget where her feet were.

Potentially lethal in situations like this.

I heard her call again from high above me. I squinted, but couldn’t make out her distant shape in the starlight. “If you get tired of leading her, I’ll do it some. You can ride Goldy.”

“No, I’m good.” It wasn’t that late; I still had some walking in me, despite starting at sunrise. It was only going on 11 PM. We had been in similar situations in the Hat Creek country many times before. We both knew that we likely wouldn’t feel the flat of a bed until two or three in the morning.

And then, thinking, I stopped for a moment. My mare, Bobbi, softly pushed her muzzle into my lead rope hand. It was still silky smooth, like that of a colt. I gently rubbed her nose. She too, was young, and she would eventually learn. I doubted that she would ever be a Goldy, but she did move nicely, and was a pleasure to trot out on even ground, and could out-walk any cow.

In the dark, I could hear the call of an occasional canyon wren still clinging on to the hope of a return call, despite the black. And I could hear Melanie clattering fearlessly, horseshoe iron on steel, occasionally sparking above on the rocks, keeping the flank intact.

She was 25 now. And now I remembered back to when she was 11, in this exact same place.

It was the same time of night, and we were trailing just a few head of strays down the Pig Creek Trail. They were mother cows, each with a baby in tow. An occasional hum by the mother was returned with a quiet utterance—a low bawl from baby. We couldn’t pressure them very hard, or they would separate. The cows knew the trail so well, and we only needed to be there to ask them to keep going rather than bed down for the night.

So we rode above them, as we did now, picking our way on horseback through cobble and rocks on the terrasets.

In the black.

I could barely hear young girl Melanie in the canyon quiet. She was softly weeping, riding behind me, on her seasoned mare, Shippy. The horse was practically born in these canyons, and could safely walk over, up and across anything. My mare, Missy, was a business mare, and was absolutely certain and sure of every footfall.

I let her cry for a moment, wondering if she banged her leg on rock or brush as we walked on in silence, high above the ghostlike blackened shapes of bovines on the trail below us. And then, as the sad murmuring continued, I turned as I rode (couldn’t see a dang thing anyway), and asked her.

“What’s happening Goudie?” It was my nickname for her. I knew not of its origin. It was just one of those names that simply happened.

She took a breath, and just told the truth. “I am so scared up on this mountainside. If we go down, we are dead.”

“I know. But we just got to trust the horse. They aren’t scared, and we are safe with them.” I knew she could feel the tension, if it existed in the horses.

It didn’t. They were calm and at ease.

And then I had another thought—the ‘what if’ clause. “But short stirrup it anyway.”

Short stirrup is riding with just your toes in the stirrups. I was glad I did on several occasions when I was on hillsides like this one. Horse goes down, and you don’t want to be caught in a stirrup.

You want to part ways. It’s better for the horse, and human.

And now, here we were, nearly 15 years later, in Pig Creek Canyon. I was the one to get off my mare, me, now afraid of falling.

And Melanie was the one running over the goat rocks astride a would-be bucking horse.

I started walking again, as they were getting a little ahead. I got down on a wider terraset, and remounted Bobbi, and clicked her into a slow trot. She moved easily, and within a few minutes, we reached the tail end of the cattle, the drag as cowboys call it, of the thin single file line of cattle bound for Little Hat.

On the Pig Creek Trail.

And I smiled. Here I was, old man of 57, relegated to running drag. There was a girl—no, a woman, a much better horseman than I, ahead of me in the black, lit only by the heavenly light of Jupiter, route finding her way down the unforgiving rock and brush defile of Pig Creek for the benefit of cattle and horse.

Both of our horses knew not where we rode—they had never been in Pig before. So all the brushpopping and trailhopping was up to us humans, in the maps of our minds. We only knew the way down where the old trail wound its way down over cliffs, through trees and brush.

And I was on the drag. I kept my lips sealed from giving any direction, and only uttered the reassuring and low voiced word to the lead that the drag was on task, meaning that they weren’t dropping anyone off in the brush. It meant that the drag had an ear to the sides of the trail, as well as the back, for a twig crack could indicate someone had dropped out.

“Come on, kids. Come on, you young ones. Easy does it, now. Heyyyyyy-Yoh.”

So far so good. But I knew that the trail had washed out ahead, and now, in just several hundred yards, a low cliff marked its abrupt end. It was only 10 or 12 feet down off the edge, and wasn’t quite vertical. So if anyone tipped over it, they would probably be able to pull it together before hitting bottom with impact.

I wondered. Would she remember? This was a new position for me, for long I had been the trail boss, yelling back behind me to drag or flank rider that the trail swept across the wash ahead. And most times, it was daylight, and you could unravel the trail through the brush and rock with your eye.

But now, it was dark. I looked up at Jupiter, a white hole in the black velvet of night. And I looked at my stirrup, as a river of sage, rock and grass flowed by. I could barely make it out, my dim light vision receptors—those rods divining black from gray.

And then, I saw the leads of herd bend ever so slightly and pick their way down through the black of brush, navigating the washout into the gulch bottom of the sand and rock washed floor. Silently, the rest of us picked our way down the off the aged trail, now bushwhacking into the thickening black of head-high sage off the bluff and the low cliff.

She had found the way, because she remembered in the map of her mind. Wordlessly, my daughter had guided her charges safely, quietly down, and picked up the broken trail again after crossing where the flash flood wash had erased it.

She now knew the land by feel. It was now hardwired into her brain, this skill, this knowledge, this art.

It was more than visual; that was only one cue on which to feel, to map in one’s mind with the trail and time spent on the range. She, like I, was seeing it through the scents, the echoes of sound, and the feel of the radiant heat off the hills. The ghosts of occasional trees in the dry wash of Pig; a rock, a cliff to clatter over.

Then, there was a unconscious timing of miles counted by the continuous cadence of hoofbeats. All were clues that filled in the gap created by a lack of vision, and this young woman had arrived.

And her proud father quietly continued working the drag, satisfied not only that our droving was nearly done for the night, but that his daughter knew the range maybe even better than he.

May you even on your darkest paths find your way by feel; happy trails to you all.

Glenn, Caryl, Girls and Cowhands at Alderspring

Daniel Jardien du Maurier

Thank you for recommending ‘Nourishment’. Looks like a terrific read!

Leonard Zamkoff

Glenn–This may be my favorite of your writings. It is beautifully honest, and real.

Glenn Elzinga

Thank-you, Leonard.

JKay

Love your stories. Hard work, yes, but a great life y’all have in the outdoors.

Glenn Elzinga

Agree. It is a great life!

Jim Gibson

I always enjoy your stories, thanx again. Jim

Glenn Elzinga

Thank-you, Jim