The wind whipped across the basin with a pesky cheek-stinging flurry of horizontal snow. It was just a week ago, in mid-April. Caryl, border collie Clyde and I were on a quest: to find a sort of black gold, deep beneath the rolling hills of sage and grassland.

We were in Bear Basin, and it is the highest elevation non-timbered sagebrush ocean habitat on our range. It is an area just short of enough precipitation to support forested lands; a little higher up dense patches of aspen and Douglas-fir blanketed the hills.

Clyde and I walked over the wide gut of the basin, called that because all surface water that drains from the 8 square miles of pitch and roll grasslands passes through here. At this point near the base of the basin the land narrows to about 100 yards wide, covered with knee deep blue-bunch wheatgrass spattered with three-tip and low sagebrush. I stopped for a moment, face turned away from the driving snow, looking away over the gray and brown hills.

No grass was coming up yet at this elevation, and there were still patches of snow here and there. There were only last year’s ghostly bunchgrass skeletons shaking as if from the cold, still anchored over the wet soil surface. They were guardians of hope; from their bases, green would rise again, and the basin would once again be cloaked with the verdant wave. As I scanned the vacant landscape from one horizon to another, an image in my mind’s eye began to take shape.

It was about a 100 years ago.

Let’s say it was in early October in the year 1920. American agriculture was still reeling from the up ticking tidal wave of a bullish market of nearly every foodstuff commodity, a burgeoning precipitated by World War I. Doubling and tripling wheat prices started an insanity of unprecedented sodbusting in the Great Plains, and the result was an immediate shortage of grassland for the country’s insatiable appetite for beef.

And cattlemen looked to the hills. The western hills, that was. The foothills and rolling grasslands that led to the Rockies suddenly looked extremely attractive to a cowman in search of grazing. Covered wagon trains had passed them by as wasteland in the mid-1800s and continued on their way to Oregon and California. But now, these semi-arid hills were a land of green gold—endless grasslands, there for the taking. A few unusual settlers had stopped their wagons with a vision for harvesting what was already there instead of the plowing it under. But those early cattlemen were few. Now, with the advent of war and the sodbusting revolution, hungry cattle flocked to the high country guided by cowhands from every walk of life.

Range riders packed lever action rifles in those days as saddle guns, handily dispatching unsuspecting grizzlies and wolf packs that descended on grazing herds, until the predators became no more. And so, with the top of the food chain extirpated, ranchers ruled, and they took it all.

And there was a lot to take. Old journals refer to grass as at least stirrup high, or tall enough that you could lose your cattle in it until they grazed it down. There was little mention of the dominance by sagebrush that we see now, a hundred years later.

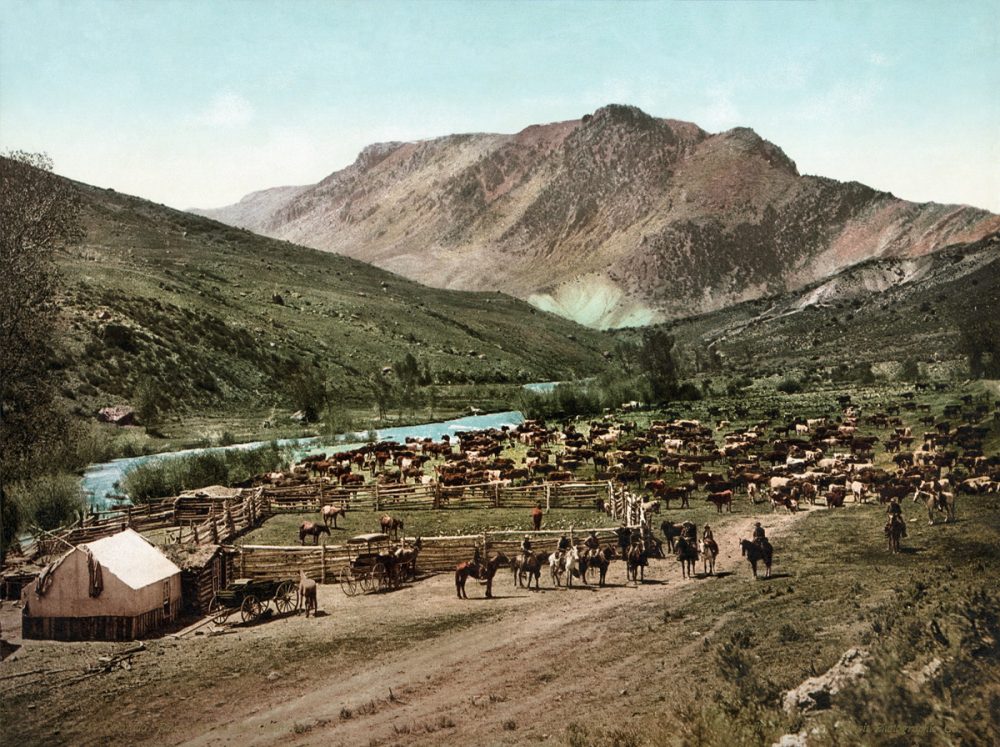

Look over there; can you see them? In that big flat on the east edge of the basin. Let’s let our minds conjure up an image of thousands of head of cattle, and it is based on the reality of eyewitnesses, old or gone from this side of eternity. The weather is spitting snow, just as I feel in the present, but instead of spring, it is fall. Around the bawling throng is nearly 40 weather-beaten and seasoned riders on rawboned, long-legged horses unlike those we see today. Horses in that day were bred to long-trot mile after mile, and they rarely had time to get fat. They were different because people selected them for one thing: work. Pleasure horses were few and far between.

From the numbers cited by some of my aging present-day neighbors in the Pahsimeroi Valley, there are upwards of 3000 head of cattle in this bunch with calves on their sides, and last year’s yearling calves in the bunch. That makes nearly 9,000 head on this mob, generating a fair cloud of volcanic dust, even on this snow-flurrying day. Some of the older folks said there may have been as many as 5000 mamma cows in that bunch, meaning nearly 15000 total head of cows, calves, and yearlings.

This is the fall gather, where all the cattle scattered over about 200 square miles are brought together to the broad reach of Bear Basin. Here, yearling cattle were sorted off to embark on the one-week journey on the long trail via the Beef Road, the market conveyance cowhands herded their cattle down to get them to the railhead in Mackay, Idaho, 85 miles away. There, they would load into railcars, bound for massive midwestern stockyards and packinghouses in places like Kansas City, Omaha, and Chicago.

These numbers are more than 20 times the amount we trail and graze through the same area in Hat Creek today, and it is unthinkable that the range as we see it could support such numbers in perpetuity. Today, there is simply not enough grass. Did something change?

Caryl, my wife, ranching and ecology partner and I think about such things often. These are the nagging, niggling ecological questions that vex us, along with questions about beavers and bison, and even the indigenous peoples component of that pre-settlement living ecosystem. The Hat Creek Range we graze on is one of the most intact native species ranges we know of. There are very few non-natives. The plant list of 2500 some species is little changed from what it was 300 years ago, as near as we can tell. So, what was the difference? Why 9,000 head of cattle a hundred years ago versus today’s high capacity of 400 to 500. What changed?

So then, again, it’s a historical perspective we call on. Let’s roll back the clock another 100 years. The year: 1821. And this flashback is not based on anecdotes, trapping journals or old paintings or photographs. It is only based on what Caryl surmises, based on the physiology, and growth habits of the range and riparian plants she knows and loves (thankfully, most days, she loves her husband a little more).

“Despite popular misconceptions, the plants here in the Great Basin and the Northern Rockies are decreasers,” she likes to remind people. That’s a PhD plant ecologist’s way of saying that the grasses in our environment cannot handle continuous grazing. In contrast, grasses in the Serengeti or America’s great plain’s former tallgrass prairie have adapted to repeated grazing and increase their abundance as a response if they get sufficient rest between grazing episodes.

Our grasses, on the other hand, decrease in a period of just a few years with continuous grazing and even disappear. Gone.

The difference? “It’s all about where the growing points are,” she likes to say. These are the sections along the vertical stem of a grass where the cell division takes place, resulting in increased grass height over the season. On those grazing adapted plants, the increasers, the points are low, near the soil surface, and grazing animals often do not eat them. They stay with the plant. And that means that the plant can easily grow back with minimal energy requirements, because it doesn’t have to regenerate those highly specialized growing point cells. And the sooner it grows back, the faster the plant can resume photosynthesis, the solar collection mechanism green leaves utilize to feed all plant processes with sugars. The plant thrives.

But with decreasers, the growing points are high in a mature plant. Often 4 to 12 inches off the ground. And with repeated grazing, an animal will eat them off. And if that is repeated year after year, the plant’s energy budget is exhausted.

The result: the plant dies.

“Prehistorically, there simply weren’t the huge herds of ungulate grazers in our country,” Caryl says. “And plants didn’t adapt to that sort of repeated grazing like they did in the more moderate climates of the Great Plains. In addition, the ice sheets left the Rocky Mountains just a short time ago—only 10s of thousands of years. There were few large animals that grazed the new colonizing plants, and there was no pressure to adapt to that sort of grazing.”

So, what did the Bear Basin country look like just 200 years ago? Good question. Caryl guesses that all the same plants were there, but their frequency (or relative numbers) were different.

One of the clues comes from the sheer numbers of cattle that used to graze up in Hat Creek at the beginning of the Beef Road in Bear Basin. As a rancher, I know that even the densest stands of the dominant grass that is here today, bluebunch wheatgrass, couldn’t support such intense grazing by those sorts of cattle numbers. There had to be more biomass to feed them. And it wasn’t just the density of plants per square meter—it had to be the height of the grasses to yield enough tonnage to feed that many cattle.

Another clue can be found on the hills of the Hat Creek ranges, where 8 years ago, we have started practicing a new method of grazing we invented. It’s called inherding, a word coined from the intensive, intentional herding of animals to mimic the occasional non-continuous grazing of native grazers such as elk, bighorn sheep, and bison. We’ve changed from a relatively continuous model of grazing to one that averages 5 years before a given plant gets grazed again. And it is starting to change the way the landscape looks.

We’re seeing one plant in particular show up that we’ve never seen in upland habitats before. It’s called Great Basin Wildrye. This grass is the tallgrass of the Great Basin grasses, and can grow up to 8 feet high, offering biomass to whatever grazer finds him or herself eating it. The plant is massive. And it cures out to twice the protein levels of our other shorter native bunchgrasses and introduced wheatgrasses. It is amazing winter forage for wildlife. But it has an incredibly tender and vulnerable Achilles heel; it has growing points 8 to 12 inches above ground. And any self-respecting cow would happily eat it to 4 inches in height. The result after several years?

Death. Extirpation.

Its long-lived seed must still be there in the soil because we are finding it colonize in areas that we guess it may have been eliminated by overgrazing nearly 100 years ago. Rest from grazing or a cool fire can cause it to sprout. In fact, in the 2018 Rabbit Foot Fire, that burned 8000 acres of Hat Creek’s ranges, much of it is now coated with young seedlings of basin wildrye where it did not occur prior to the fire.

We’re seeing it on Hat Creek, because we have changed the grazing pressure from continuous or yearly to an average of every 5 years. The plant can handle some grazing; after all, native grazers like bison, elk, deer, and wild sheep have always picked at it. And it turns out that light grazing does help the plant in the long term, because every time the plant is grazed with long intervals of rest, the roots die back, commensurate with the leaf area removed. All plants do this as a mechanism to maintain efficiency.

And that root die-off is where the story gets even more interesting, and why we are wandering around Bear Basin in a snowstorm.

When a plant is grazed or otherwise disturbed above ground (say from a cool fire), the plant will achieve energy balance by sloughing off roots. Root cells require energy just like any other living cell does, and that energy requirement is met by photosynthesis in the green leaves above ground where sunlight, carbon dioxide in the air, and water create sugars- energy packets. When there are no longer enough green photosynthesizing plant tissues above ground to support the roots, some of the roots will die.

And those roots are made of carbon.

The dead plant material, deep within the soil profile, changes the health of the soil dramatically, supporting more life underground. It’s organic matter. Living soils are defined by organic matter, and plants thrive on soils that are alive, partnering with bacteria and fungi to translocate water, oxygen, nutrients and even sugars across the soil profile.

So grazing is important, and key to maintenance of healthy ecosystems, just because of this occasional root death, and the humus, or organic material that gets deposited deep down in the profile. It’s one of several ways that nature injects organic matter into the ground. The only other ways are also through disturbances such as fire or winter kill. Simply leaving grasslands alone without a disturbance grazer or event causes them to stagnate.

Basic fact in soil: all life requires dead material to live on. Soil biota without roots living and dying eventually have nothing to eat.

Great basin wildrye has long roots. They go up to 8-12 feet deep into the soil profile, deeper than most grasses. And they deposit incredible amounts of deep organic material, especially when grazed occasionally. We see it in basin wildrye stands on our home ranch. Black dirt, deep and rich.

And in the year 1821, Caryl and I believe that deep, black soil was prevalent even in Bear Basin, due to solid stands of basin wildrye, especially in the bottom swale areas where Caryl, Clyde and I were standing in on this cold and blustery April day. Fact of the matter is, we think it was true on many of America’s dry rangelands, but now, much of that within a few feet of the soil surface is gone from continuous grazing and exposure to wind and drying due to lack of plant cover. Soil exposed to wind and sun is a perfect recipe for destruction and conversion from soil to dirt. These are the elements of desertification that have all but wiped out many of the world’s grasslands.

But there’s more: organic matter is about 55% elemental carbon. Plants like wildrye were huge carbon sinks, locking away the black element from ever becoming gaseous carbon dioxide and then affecting the Earth’s atmosphere.

But none of this is for sure, about whether wildrye formed the feedstuffs of beef for hungry America. It’s hard to research something that no longer exists. Continuous grazing happened and is still happening nearly everywhere in the West, wiping the slate clean of clues.

But Caryl and I began to wonder: was there perhaps a record written underground? Could we find the black soil—a sort of black gold to Caryl and me—deep below the soil surface, that still existed from 200 years prior?

So. This is what Glenn and Caryl do for a date when we have a little time off. We go exploring.

“I’m freezing my butt off!” Caryl stated, voice raised over the wind. “I’m going to sit in the truck until you find a spot.” (Not quite the romantic date I had planned.)

I nodded, and Clyde and I continued across the flat, down to a deep wash in the middle of the narrowing of Bear Basin, where all the water that falls in the basin must go. I knew immediately what this 15-foot gash in the soil was. A memory of a conversation with an eighty-four-year-old friend, one Dick McDaniels, from 12 years ago came fresh. I found myself wishing he hadn’t passed away as I missed his friendship, but also, his stories.

“It was in 1959. I used to run sheep up here.,” his gravelly voice stated. “Them clouds gathered up over the head of Bear Basin and dumped likely 6 inches of rain in just an hour on one August day. It was so much water that it just carved up every depression and draw on the land.” Dick went on to say that there was no other gully-forming event on the land he’d seen before that, and I’ve never found others. Apparently, the “washes” on our rangelands were a recent phenomenon. It didn’t look like they occurred before 75 years ago, because they weren’t everywhere. Dick just thought it happened because of the extraordinary amount of water the cloudburst yielded.

I tend to think that although that was a factor, there was something more. After all, cloudbursts always had occurred on our ranges. August downpours from massive thunderheads are relatively common and happened long before European settlers arrived.

Caryl and I both thought it had to do with the presence of plant cover on the land. With a healthy stand of plants on the rangelands, two things happen: first, rainfall impacts are minimized by the soil holding capability of complete vegetative coverage; and second, rainfall is rapidly absorbed by a living soil sponge when soil life is at its maximum. We see that on our own ranch at home when our soil organic matter went from 2 to 7.3 in ten years. No longer does water collect or even travel across the ground. It goes in.

And I was thinking the deep gully wouldn’t have existed had the plants on the land been intact. But the “cut” in the gut was exactly what Caryl, Clyde and I needed. It would give me a ticket to the underworld of the soil surface. I could conceivably get even 12 to 15 feet underground by using the near vertical cut bank of the draw and fast-track my shovel to deep below the surface by a simple side excavation.

I told Caryl what my idea was, and she, although intrigued, opted to let me dig with Clyde and stay out of wind and snow in truck. I grabbed shovel, pick and trowel, and sample bags, and dropped deep into the draw for my excavation.

And dug. For black gold. In search of soil and not dirt.

Plant roots from the bluebunch-sage that was existing now on the surface went deep and colored the soil darker to six feet or so. But I was looking below them, and finally, at 12 feet below surface, I may have found paydirt: a streak of black stared back from the hole at me. It was a deep, uniform layer of dark speckled dirt. I excavated a sample, dropped it in ziplock, and the soil lab we worked with would tell us if was just looking at black mineral soil or deep carbon.

I’ll know in a few weeks. But for now, Caryl and I think we may have found a clue that will guide us on a path to regenerating more rangelands to the tall and vibrant grass resource they once were. And the incredible carbon sequestering sink that they could be.

And maybe cows can save the planet.

Happy Trails.

Doug Dockter

Great article, Glenn! I can hardly wait to hear what the lab says. I hope you’re all doing well and ready for “the season.â€

Terry Allaway

PLEASE please please follow up with us on what you find from your soil sample! This botanist turned permaculturalist is super excited about what you are doing. I haven’t heard anyone really talk about Great Basin Wild Rye since college days when my botany professor spoke longingly about the great stands of horse-belly high grasses that once dominated throughout the Great Basin. I have always wondered since then how it could be brought back and have often gazed into the distance there trying to imagine the range without the dominant sage that everyone thinks is just the way it is. Love your weekend stories, Thanks!

Deborah Olsen

I think it’s truly amazing by doing your own research that you discovered something that may save the blue-bunch sage. I am enamored by your endless drive to find new ways to save the grasslands that once existed, if only more would do the same our world wouldn’t be in the spot that it’s in from taking so much from Mother Earth and not giving back. Thank you for all of your hard work and blessings to all of you for everything you do!!

Sincerely,

Deborah Olsen

Cindy Salo

Glenn,

Your mention of decreasers and increasers was a blast from the past. Rangeland managers used to use the terms a lot, but you hardly hear them anymore. Our language shapes our perceptions; I hope we don’t forget that bluebunch fades away with heavy growing season grazing.

I hadn’t wondered if there might be more sagebrush now, after heavy grazing in the late 1880s and early 1900s. That would make sense—sagebrush must be the ultimate increaser. But we live in a shrubland, not a grassland, so I think sagebrush will always have an edge here. Grasslands develop with growing season precipitation: summer storms move up from the Gulf of Mexico to water the Great Plains. Shrublands develop where winter precip moistens the soil and grasses have to get all their growing done between the cold of winter and the dryness of high summer. Shrubs have an edge, as they can use deeper soil moisture than the grasses.

…Unless there used to be a lot more deep-rooted basin wildrye! I wonder if it can go head to head with sagebrush in reaching deep water during our dry summers. Say, you might be on to something. (What a wonderful grass basin wildrye is; great to hear that it’s coming in after the Rabbit Foot Fire.)

I wonder if your dark soil layer is a buried A horizon. Sounds like enough water moves across the site to bring in alluvium on top of an older soil. If it’s a buried soil, I wonder what phytoliths could tell us about which grasses dominated on the buried soil and on the current soil.