As I left a note for the outrider horseback crew at the tiny outpost, or spike camp known as Aspen Spring Camp, I heard a twig snap. There, just 100 yards away, a thin line of wayfaring and lost-to-us Alderspring cattle picked their way across the down logs in the thick fir and aspen forest. I placed a rock on my finished note-paper in the middle of the table so the crew would find it, and counted the black Angus beeves as they trailed on the game trail through the trees.

There were 10 of them, and they didn’t spot my motionless form. They were all yearling cattle. It was funny, I thought, as I had just seen 10 in the last group I spotted as I did a big circle ride coming up out of Park Creek, over 6 miles away. I had surprised those as they quietly grazed an open grassy meadow along the creek, and when they put eyes on me, they trotted into the dark timber, even as I talked to them. I got the sidelong glance that betrayed a little mistrust, it seemed.

And that in itself surprised me. After all, they knew me. I was no stranger. But it almost seemed as they’d slipped back into their foundational instinct of the ancient relationship they all knew in the core of their being: I was a potential predator.

And they were potential prey.

As I made my way from spike camp that day into the high timber of Big Hat Creek, I thought upon my observations. I’d always watched our bovines, and had learned tremendous amounts from them. I knew that there was far more to learn, but this was a total curve ball.

I cut some tracks on the trail I rode, and judging by the edge and lack of dust on the sign, I knew I was on the heels of more ungulates. I had to stop and check these tracks a little more; the gravely dirt was hard to read, and it could have easily been elk. After all, our yearling beeves had about the same size print of a cow elk, and we shared the country with many wapiti.

As I dismounted and knelt in the dirt for a moment, I knew my quarry by the little less rounded appearance to the cloven hoof print: beeves.

When I mounted again and rode just another mile, curve ball became another strike, making it a clean three, and I was out on this one: again, now another 4 miles away from Aspen Springs and the last 10 head, I spotted them: another 10 head, in deep, sun dappled grass of a high alpine meadow on a mountainside of Big Hat.

And so, I was struck out as I was stumped with the incredible coincidence of tens.

They were miles away from each other. Who told them to find 9 head to team up with in their wanderings over 30 square miles? No more, and no less. Three sets of ten. Chalk it up to coincidence? I thought that highly unlikely. I needed additional data.

Later that night, I met the main crew over at Iron Mountain Camp, about 4 miles away from the Spike camp and the 3 riders I had working out of there. Over the fire and by lantern light, I asked the crews of riders what they had seen. It was Melanie, Jake, Linnaea, Caitlyn and Annie. Two of them had split from the main herding base on and off through the past few days to go what we call “cow hunting,” the business of gathering strays back into the herd.

And we had a lot of strays. Over 160 at last count. They could be anywhere, and could literally walk a hundred miles.

And you, dear reader, are probably wondering how we ever lost that many cattle. It was the brainchild of none other than yours truly, reinforced by my always curious bride and PhD biologist, Caryl.

We coined a new word, back in early August. We called it outherding. Caryl and I wanted to try it. We had been doing the super intensive and intentional herding of 400 head of cattle for 7 years straight (we coined that practice “inherding”), directing them every step of the way on horseback. But why not let the cattle choose where they wanted to go, hopefully together, say in a 6000 acre area of mountain and forest?

We chose an area to try that had experienced dramatic recovery from inherding. Aspen forests were returning, fish habitat was restored, and even the upland dryer grasslands showed more promising diversity and resilience than we had ever seen them represent. It was regeneration run amok, and the woody trees along creeks had so rebounded that it was hard to walk along the creek. The Forest Service agency folks even complained because their creek side monitoring plots had become inaccessible for humans!

After seven years of inherding by us, these creeks appeared to be resilient enough to let cows roam again. With outherding, we figured we would ride the entire perimeter of the intended grazing area to keep the 400 head within that piece of country. Riders would also patrol creeks horseback to keep the beeves from camping out along any piece of given live water, thereby preserving fish and bird habitat nicely.

From everything Caryl and had read and absorbed from stockmanship experts from all over the world, once we had created a well-connected herd of bovines, the herd instinct would have rebooted, and the animals would generally stay together in one large bunch, moving on their own across our landscape, similar to ancient million head herds of bison on the great plains and wildebeests on the Serengeti.

All they would need is occasional reinforcement by us to maintain the herd integrity. Perhaps the herd would split on its own, they said, and we would need to re-connect them. No problem! Easy-peasy!

After all, we had trained them to roam together since May. And it had worked. Our pressure to keep them in a bunch was now greatly reduced; it seemed that more than anything, they had bonded as a large group, and all we needed to do was to direct them not in the “how” of traveling as a bunch, but the “where to?”

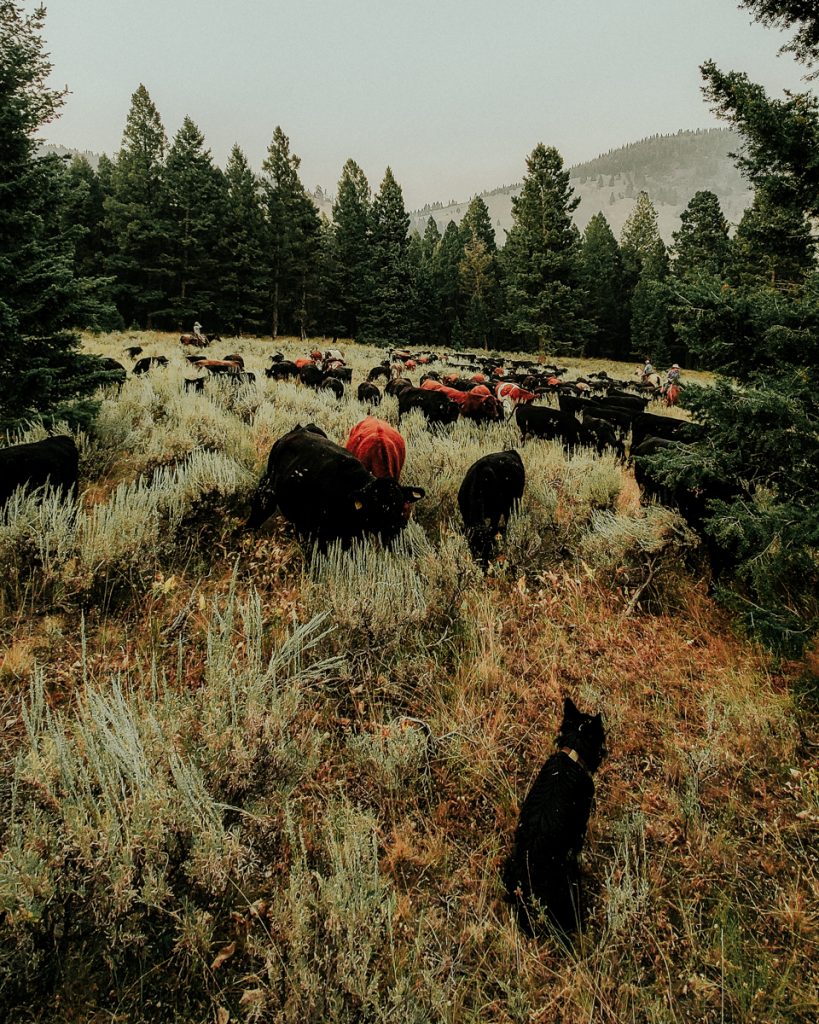

So, on August 4, we decided to see just how “booted” their herd instinct was. It was high summer, and we crested the high and windy pass between the Park Creek watershed and Big Hat. The grass was waving in the wind, undulating in ocean-like waves on the broad saddle-like divide. The crew simply turned them loose, and sat quietly on their horses as the beeves fanned out in a broad herd to ride the amber wave.

The horseback crew watched in a line, caressed by the casual breeze, eyeing their charges as they went their way unattended down over the rim into the dark timbered slopes of the broad basin of Big Hat. From their vantage point, they could see the entirety of the watershed: there, about 5 crow-fly miles straight away was the next saddle that broke over Iron Mountain into Main Hat Creek. But between the two saddles lay several canyons and thousands of acres of forests and creeks broken by aspen and sagebrush fingers.

It was a lot of roaming country.

For several days, the crew monitored the herd loosely; they appeared to stick together in a sort of connected mob. After about a week, some separation appeared. The crew rode damage control. Linnaea was boss that week, and started to have a little separation anxiety. After all, Melanie and Linnaea had hacked herding for the last 6 years, and were dang good at it. To let it all go and lose control was almost too much for human with habit.

At the end of every few days, I had crew bosses get a general count of their herd. For the first week, the herd held close to the 400 we deposited into Big Hat. After 7 days, there seemed to be consistent results that yielded counts in the high 300s.

The herd’s cohesiveness was cracking, and beginning to fragment. It was going against what every stockmanship and animal behavior expert had told us.

After 2 weeks, the dispersal began in earnest. The herd fractured into smaller and smaller groups. Riders put hard and long miles on horseback trying to put them together, but the cattle were changing psychologically, it seemed. They no longer hooked as well on each other, and became increasingly skittish.

Three weeks went by. It was time to move the herd to the slopes of Iron Mountain. Jake and Linnaea co-crew bossed as they gathered cattle from the four winds of Big Hat in an attempt to put all 400 into Iron Mountain.

They were failing.

The shortening days of late summer were starting to really represent their true character, but it helped that the moon was a waxing gibbous. And so, at the end of the long day gathering and moving all the cattle they could muster in one bunch, Linnaea and Jake still rode, leaving worn-out crew in camp. Now, each alone, they continued through blackening forests lit only with moonshadows, each with around 10 head in their charge, following game trails to the pass on Iron Mountain.

And trails converged in the forest below the pass. Cattle joined and the two riders connected. It was just past midnight.

Linnaea, exhausted: “I’m so done with this.”

Jake, frustrated: “We’ve got to quit this s***.”

And so, early the next morning, I received a satellite text message from Iron Mountain Camp: “STARTED INHERDING AGAIN. CREW UNAMINOUS.”

And so began the several weeks of “cow hunting,” picking up the dispersal of beeves that occurred over the wide landscape. We ran two crews; one to inherd, and the other to gather from the 4 winds. And now, after my own patrol and locating 3 ten head groups, I was in Iron Mountain camp interviewing the cow hunters about what they found.

And it was the same, always: the beeves had been gathered from 20 square miles in usually 10 head groups. Sure, some were 8; some were as much as 12. But most all averaged 10. There were some multiples of ten found: twenty here and thirty there, and an occasional anomaly of 14 or 16. But some on the crew thought they were groups that had joined.

Several days later, I was back up on horseback cow hunting myself. Pickings were definitely slimming down. We were now only out by 60 or so. After cutting some tracks, I found a little bunch, high up in Big Hat on a north slope, resting in deep green.

They spotted me and ran. Fast. I went after them, keeping distance, and as they lined out on a game trail, I counted: nine.

After riding alongside for a bit, they began to calm down, accepting my distant flanking presence. I was getting some remembrance—of recognition, I thought. After all, they’d lived with us for most of their lives.

They finally settled and put their heads down to graze.

It looked as if they were considering settling down to being domestics again.

When we turned them loose, it was as if over just a few weeks they actually rebooted to wildness after the herding pressure ceased. And talking about it later with Caryl, we realized that when we observed wild bison and elk herds in the mountain west with forested and broken country environments, it seems like nature creates a new norm for big herd animals.

Smaller herds. Let’s call them bands.

We surmised that predator pressure in the diverse and hiding place dense landscapes had created such instincts; larger herds in thick forests would have conceivably lost many animals to easy pickings by wolf packs who would wisely just live along the periphery of the moving herd. Wolves and bears followed them on the Great Plains, as they do on the Serengeti. But there is safety in sheer numbers in those situations. Only the stragglers would get picked off. Venturing into a stampeding herd was certain death by trampling. Pretty risky for a predator.

But in mountain country, ungulates seemed to disperse into these bands, especially in landscapes like ours that support many wolves. A given pack of wolves simply can’t follow all small 10-head bands of animals. And yet, with 10 head, there would be enough number for self-defense against a group of predators, like a wolf pack. I have personally witnessed cows getting really aggressive against canines to the point where canine is dangerously injured. In contrast, solitary animals would simply be surrounded to their eventual demise with fang and claw on all sides.

And so, 10 head. A safe number. From deep within the darkened halls of animal instinct, Caryl and I are thinking. Not always 10, but it’s the critical mass that they seek. A feeling of security that resonates.

As I sat horseback, quietly watching my 9 charges grazing calmly in the thick green below the protective fir forest, I heard a twig snap uphill from the beeves.

We- that is, cattle, horse and I- all turned to look and see what was coming.

It was a lone black steer, trotting briskly to catch up in a sort of “wait for me” heads-up motion.

Now, the band was complete, at least in the ungulate’s mind. More than coincidence, I think. Who knew that cows could count? Could it be a new form of Cowculus?

Happy Trails.

-Glenn

Lily Tinkle

As an ex-behavioral ecologist, I really enjoyed reading this, Glenn. What an amazing observation! I urge you and Caryl to publish in a journal.

Also, the sheer amount of work that you all put into your endeavor is very humbling to those of us who benefit from your labors.

Much respect to each and every one of you.

Leo Younger

Better than any fiction.

Dave

That’s very interesting 🤠and funny “cowculous”!

Deborah Olsen

These stories never fail at being a “good readâ€, you should consider writing a book I’d buy it! I love hearing how life truly is being on the ranch I have a new perspective of how hard you work but also love what you do it’s magical!