Dear Friends.

“Pet.” I looked at her as I spoke, and the mare’s ears rotated back as she heard her name. In response, the big Belgian leaned forward into the great leather collar, conveying true horse power to the thick cowhide tugs behind her. There was a brief jingle at the beginning of the pull, but now that was silenced as all was taut and unwavering. The doubletree chains glistened in the high noon sun as if they were magically transformed to solid steel, humbled thereto by the sheer magnificence of draft horse power.

Pat was her equine partner, on the left side of the buck rake, and I saw her eyes and ears flick back in attentiveness–but not in movement. They knew their names, despite being pretty green at the rake, and Pet moved on, while Pat stood, a little nervously treading the ground, alternating her massive hooves in place as I held her with a gentle but steady hold on the snaffle bit.

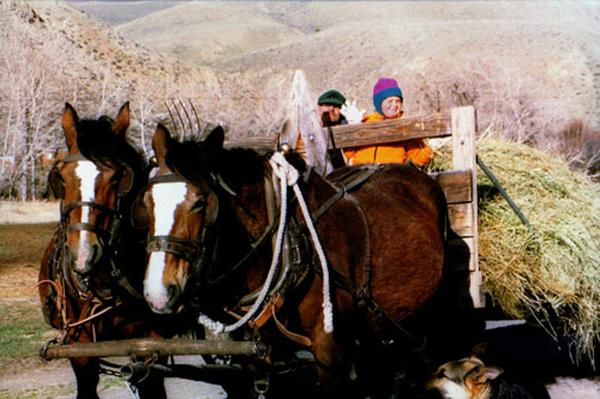

Above: Pet and Pat in their later years, with Melanie and Glenn behind them on the haywagon.

The loaded rake responded to Pet’s slow walk, and began a wide arc around the pivot of Pat. The two horses were oddly about 12 feet apart, separated by the long wooden teeth of the rake itself. It could hardly be called a rake, as it had no tines pointed to the ground. Instead, it was armed with about 15 tines of peeled and pencil-point sharpened lodgepole pine tree trunks, each about 2 to 3 inches in diameter, and about 10 feet in length, laid out in parallel, emanating from a common wooden frame. Most of the odd contraption was made of pine and fir wood from the local hills, fit together with a few key pieces of iron and steel hardware bought at the feed store in a buckrake kit a short 70 or so years prior.

Although rusted and brown, the iron parts paired with the wood made a well-oiled machine. The cast iron seat I sat on was part of the kit, and I was grateful for the humanoid rear-end shape the 19th century designers placed on it. Still, I had grabbed a handful of dry hay to pad the church-pew hardness with and wore a broad brimmed straw hat to protect my northern European fair skin from getting roasted in the high altitude Idaho summer sun.

Duly noted: none of the horse drawn equipment I was seeing had cabs or covers for their human operators. Perhaps those design engineers wanted horse and human on the same level in element exposure. Testament to a lost awareness of the importance of animal as well as human welfare?

The sun rode high up in the azure blue above the still-snow speckled Lemhi Range. The ramparts of peaks vaulted up from the Clark Ranch at the edge of the meadows we gathered our leaves of grass from. It was an epic backdrop to a the fairly mundane making of hay. Somehow, the view and the reality of the big sky vista of mountains reaching 60 miles to the horizon inspired heart and soul despite the quiet and repetition of clipping and piling 300 acres of wild grass meadows.

The Lloyd and Beva Clark place was one of the last, highest elevation ranches of the long gradient of the Lemhi Valley, a sinuous trench that ran about 65 miles, pinched between two parallel 10,000 foot mountain ranges. Beyond this ranch, it was simply too cold and arctic-like in the wintertime for any pioneering soul to settle, let alone grow enough grass to sustain a herd. Wind chills of 70 below zero were not uncommon in January and February. It was why it was critical to the life and continuance of the Clark herd to store adequate grass energy to sustain life.

The Lemhi mountain range.

This day’s work consisted of Caryl and I working our teams of bay Belgian draft mares to fell, dry and rake windrowed hay, push it up in a 6-foot or so pile of the dry grass, loosely gathered on the pine buckrake tines (probably about 3-400 lbs of hay) and literally push the pile to the bottom of the beaver-slide, or hay derrick, as Lloyd would call it.

We weren’t the only hands on the crew; there would be the Selleck family (wife and mom EvaJean was Lloyd and Beva’s daughter), Larry Clark (sibling of EvaJean), and of course, Lloyd himself.

Seventy-year old Lloyd was our benevolent taskmaster, as well as our amazingly patient teacher (Caryl and I basically knew nothing about horse-power). He’d owned the several thousand acre spread (including leased grazing land) of the Clark Ranch, with his wife Beva since 1946.

And for whatever reason, they managed it the same way they had in ’46 (I personally think that Lloyd had a gross disdain for machines of any kind, and would rather work with animal than engine). Horses and mules did the heavy work on the ranch, and a guy or a gal that worked on the ranch for any time had found a pretty good relationship with pitchfork, shovel and axe (Lloyd always called that a “haxe” with his gravely drawl).

The human work was pretty much all manual, except when driving a team. Even then it was, as you were connected to your draft charges with leather line in hand, and that, sometimes, was a manual labor undertaking in itself. My early summer hands were tender at the beginning, and often after a day of haying, driving the team with the leather in hand, they would be cracked and bleeding by days end.

Lloyd would laugh, and say something like: “What happened with yer hands, Honey?” (He called all of us on the crew “Honey,” regardless of age or gender).

After learning the basics of all the hay making equipment, buck raking was pure pleasure. Caryl and I fought over who got to run the buck. There were no moving parts except the fixed in position big wheels up front, and the “crazy wheels” which could turn any which way like the front wheels on a grocery cart, under the seat on which you rode. Sure, the wheels squeaked and chirped a little as they rolled, and the wood framework and tines creaked like a ship at sea, but you could speak quietly to your team, and have plenty enough hearing bandwith to harken to the call of the wet meadow curlew, or the soft whisper of mountain bluebird as it flitted by. And it was slow enough to avoid the killdeer nest, and easily keep horse from trot, their massive footfalls slowly thumping through the soft meadows in the quest for hay to sweep up to stack.

Lloyd kept us and even the horses and mules, to some degree on a rotation through all aspects of haying; mowing machines, although entirely horse powered, still had a fair amount of clatter to them (it could get to you), and the dump rakes, with each well timed windrow dump, would get pretty wearing on the seat bounce. But the buck rake was joy, once you got the counter-intuitive hang of the lines. Their rigging was different than on any other implement, plow or wagon. The only route to control was by gentle bit pressure on the horse on the inside of the turn, and once you got the hang of it, the sensation almost felt like sailing a small boat–out in the wind on the waves of the undulating prairie.

One team of drafts mostly stood all throughout the day. It was usually the old gelding (nearing retirement), Roanie, and his partner, the black mule, Nod. They were able to graze on the abundant hay in the pile next to them as they waited to work their short bursts. They were hooked up to the beaverslide itself—an incredibly ingenious contraption that stood some 50 feet tall, made of lodgpole pine logs that launched huge piles of hay to the top of a hay stack, as much as 18 feet high. There, a worker (often Caryl or I) would talk to the team on the ground when a load was ready (brought in by several buck rakes), and they would launch the hay skyward with a system of cables and pulleys (also dating from the early 1900s).

Above is a beaverslide like the one on the Clark Ranch. These still stand dotted across the West today.

The best word I could describe the whole system of hay gathering when everything was working? Elegant. But there was something else–another elegance in this old way of work, and it sticks in my mind to this day. It had to do with the time off work.

The image associated with that thought was one I have captured in my mind: it was of Lloyd’s pocketwatch. He always kept one of burnished metal and scratched glass in the pocket of his harness-oil polished and worn-smooth Levis. The legs of Levi were a little blackened by ground in dirt, and his hands always had a crack, wrinkle and callous to them, the tiny canyons of which would be filled with a sort of blackened harness oil–irretrievable by soap or brush. Even his canvas broadcloth or chambray shirt would have the same finish to it.

He had spent a life with horse and harness and watching and moving stock on a saddle horse. The relief of the mountains he rode and lived in was reflected in the contour of his face, but abundant laugh-lines betrayed the fact that although hard, his life and living was a happy one.

I would often cast quick glances at his face as noon approached; he would take a measured eye at the position of the sun, and confirm the time with a look at the timepiece. As he tilted his head down, I would see the top of his battered Stetson hat with a sweat-stain ring around it (it also had a few black wear holes at the crunch of crown) as he peered down in the Stetson shade to his leather-thonged watch.

And when it was time, he would call across the meadow with a mix of gravel and baritone: “LUNCH!”

And it didn’t take us long to get trained up, because after a few lunch calls, we knew he meant it. If we tried to take another round of hay, or fork another beaver-slide dump, he would let us know that “the COOK is gonna be ANGRY!”

And so, we pulled bridles, grabbed lead ropes, hooked one team up to the hay rack, or wagon for the half-mile back to the barn, and led the others there. One of us would drive the wagon team; the others would ride bareback on a harnessed draft horse while leading another or simply hold a halter rope while sitting on the weathered and cracked floorboards that comprised the back of the hay rack. Some of the horses we simply turned loose to follow us back to the barn and water.

We’d stop at the crossing of Tex creek for water, and the horses would put their muzzles down in the windowpane iridescence of the clear-as-crystal spring and snowmelt waters. “Don’t let them hog the water,” Lloyd’s gravelly voice would advise, as the drink was indeed ice-cold. Then, in the cool shade of the barn, we would loosen gear and fill the mangers with fresh meadow hay. They would eat before we would. It was that way with Lloyd. He always was sure to put the horses before humans.

I think he had more patience for horse. But a love and life with them fostered a kind heart to human as well. Unless if human packed some pride. Then Lloyd simply let that pride punch said human in the guts—or groin! There were plenty of opportunities for that to happen on an animal powered cattle ranch. Hubris invariably led to broken leather, wood and sometimes bone of the cocky would-be buckaroo.

And Lloyd would simply laugh, walking away from such antics. He wasn’t too bad for rubbing salt in the wounds of punctured pride. But sometimes, he just couldn’t resist. I watched him laugh once at the visiting and more than a little proud Frenchman, Andre’ as he got launched and piled out on some rocks by a slightly cantankerous mare named Sandy. “I thought he said he could ride,” he quipped to me in all faked concern and seriousness. Then he flashed a broad grin.

Back to lunch, a serious affair. Until we arrived in their large 1890s log ranch house for that first lunch we shared with them, we couldn’t understand why that pocket watch was so important. But one visit to that kitchen was all it took. Beva, Lloyd’s bride of over 40 years prepared a glorious meal; there would be roast mutton or beef, potatoes, salads, rolls or breads, vegetables, and peaches and cream or pies and ice cream for dessert. She knew how to feed that hay crew, as she had been doing it every year for over 40 years before we came along.

Beva even pre-prepared much of it, opening canning jars full of produce from the summer before. She brought them into the light of kitchen after a winter in the still dirt-floor larder/pantry of the sprawling house (most homes in the upper Lemhi Valley finally received luxuries such as wood floors, telephones and power just 10-20 years prior).

Then, stuffed to our gills, there would be a few brief minutes to grab a siesta, if so desired, and then it was back to work. We’d find our teams again, almost by feel in the low log barn, squinting in the dark of the small slat windowed, cave-like cool.

Then, we’d proceed out to the big meadows, for an afternoon of grass harvest to hay. And this went on for weeks over the summer, gathering the precious high mountain production of wild grasses, sedges and rushes from some 320 acres of subalpine meadow, placing it in the massive breadloaf stacks, scattered over the wide pastures.

There the hay would wait, safe and secure and still green until, despite the winds of an austere high mountain winter. Lloyd, now surrounded by a bundling of wool and windproof leather and oilcloth, would load the loose hay on a sled, again pulled by a team, to scatter it along the willow and birch copse shelters of Tex creek, where his foraging Herefords and Shorthorn cattle would be waiting out of the subzero wind.

It was what Lloyd did in 1946. And now, Lloyd would do the same in 1988, as he had for every year in between.

It seems foreign to us now, that a man or a woman could do the same as he or she had done 40 years ago. Our culture seems like it doesn’t celebrate this course of the common man or woman; honest work, done daily, the same way, for half a century.

The fact of the matter is that our lives, even human history, is founded on that. It seems we’ve lost a respect for those people that just showed up. Every day. To feed cattle, make hay, herd sheep or milk a cow. We’ve lost respect for those who work under human strength or integrate with pure animal power.

For us on Alderspring, we’ve been blessed to enjoy a similar journey to Lloyd’s. We certainly learned part of our way from him and Beva. But I’m concerned for the change in culture; is there a way that just some of the next generation can possibly find their way back to a relationship with land and beast?

It’s not for everyone, I will completely agree. But all of you are still connected to some degree; for you are part of us and us you through your connection with the land and produce from Alderspring.

And in that, I see hope.

Happy Trails!

Glenn with Pet and Pat out logging.

Deb Olsen

I truly respect your lost ways of working on the range and I pray every night that more people will turn back the hands of time and realize that if we don’t change things we too will be extinct. You’ve learned how to implement scientific knowledge of today’s world with knowledge of the past and meld them together for the perfect combo. I pray more will follow in your footsteps instead of taking shortcuts to profit for themselves, for I understand that you care about everything and everyone as a whole and truly that is a gift to all.