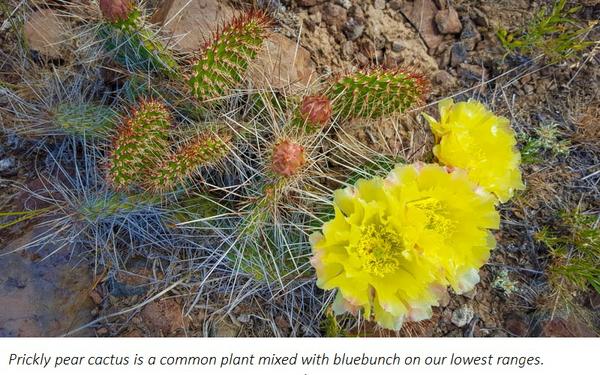

I startle awake from a dream very unlike my reality. I’m bolt upright, eyes wide open, because the lead rope I had in my hand is gone, and the horse on the other end was my only conveyance off of this rockpile. My mare, Ginger, has light-fingered her rope from my relaxed sleeping grip. I didn’t mean to doze off; I just had to lay down—for only a minute—on the rocky ground between the prickly-pear cactus and and just close my eyes. Several nights of sleep deprivation sang their siren song, and politely requested a little installment payment.

I startle awake from a dream very unlike my reality. I’m bolt upright, eyes wide open, because the lead rope I had in my hand is gone, and the horse on the other end was my only conveyance off of this rockpile. My mare, Ginger, has light-fingered her rope from my relaxed sleeping grip. I didn’t mean to doze off; I just had to lay down—for only a minute—on the rocky ground between the prickly-pear cactus and and just close my eyes. Several nights of sleep deprivation sang their siren song, and politely requested a little installment payment.

I stumble, then stand up, and I hear some clattering in the talus above and behind me. She had not gone far, thankfully. Ginger has found her occasional friend, Natty, and they are not biting and fighting. Chestnut colored Natty is loose and unsaddled, and has a day off; she was my gear packing horse yesterday that got our camp grub and personal gear up to camp for the four of us on this riding stint with the Alderspring herd on our 70 square miles of wilderness pasture.

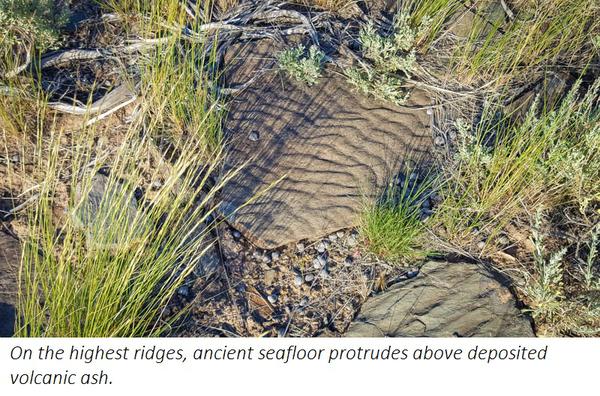

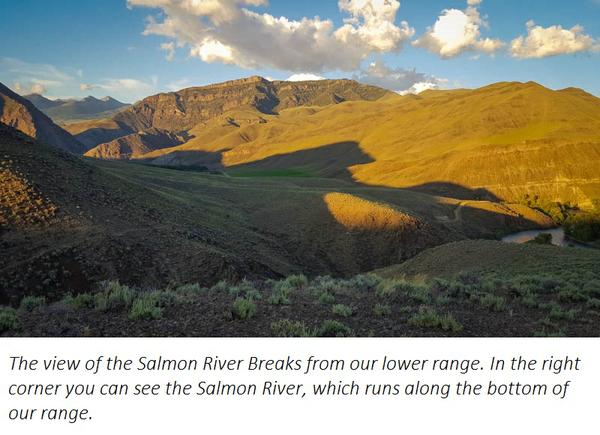

I catch my mare, and bring her back to the bony outcrop I had occupied when I drifted off my watch. This is my spot for the next few hours; a quite rocky spine on these Rocky Mountains from which I’ve been watching Alderspring’s beef herd drift upward into the unnamed basin below me. They are quite settled now, after a tough climb up here, because it’s a miniature Nebraska of grass in an otherwise rock-strewn canyon labyrinth known as the Salmon River Breaks. It’s called that because that river, now swollen with snowmelt, has carved the 3rd deepest canyon in North America in this volcanic landscape.

It is steep, as my winter-soft legs found reminder last night in the wee hours as the herd bolted and broke free from their bedding ground temporary pasture. It’s bounded by just a single ribbon strand of electric fence, a handy tool that we train them to before we leave on our range trek for the summer. But it is a more virtual fence than a real one and they occasionally make their escape. Escape was made more likely by the fact that last night was their first night in the unfamiliar wilderness of the summer range. Something startled the beeves out of their slumber just as a crescent moon slipped under the horizon, and off they went into the black.

It is steep, as my winter-soft legs found reminder last night in the wee hours as the herd bolted and broke free from their bedding ground temporary pasture. It’s bounded by just a single ribbon strand of electric fence, a handy tool that we train them to before we leave on our range trek for the summer. But it is a more virtual fence than a real one and they occasionally make their escape. Escape was made more likely by the fact that last night was their first night in the unfamiliar wilderness of the summer range. Something startled the beeves out of their slumber just as a crescent moon slipped under the horizon, and off they went into the black.

Three of us had already hit the bedroll as the beeves stampeded out into the 46,000 acre dark beyond. Within minutes, 4 little flashlight beams probed the night. And within only a few minutes more of running after them up the canyon, reflecting eyes were sighted in flashlight beam, still moving away fast. Now the work began of herding the unsettled bunch back to camp. It could be a long night, as The Milky Way spanned from horizon to horizon and the jeweled canopy light helped the night visioning beeves cover ground quickly. We had no time to catch horses, and both Cullin and Patchin ran barefoot in only partly broken-in boots. Patchin had the added handicap of his spurs still attached to his boots—the big star-shaped rowels protruding off the heels made running across rock and cliff in the dark particularly treacherous while the rest of us dealt with the slick leather bottoms and heels on ours.

We had our work cut out for us, because our route had to follow the vertical and nearly precipitous rock-strewn terrain of the skyward ridge. Melanie and Cullin, both runners, had the unfair advantage of training that enabled them to keep up with the beeves. Patchin had just plain grit, and I had the sheer cash value of 200 plus head to drive me. As we finally got into them, the herd bolted and split in half on the spine of a lonely ridge. I headed down alone into the canyon black, stumbling and falling several times along the way, and the others disappeared over the ridge, headed for higher ground. Patchin, Melanie, and Cullin sprinted after the high bunch, attempting to run with the cattle until they would settle, and I took the low.

My body was sure glad I did. It turned out that the younger part of the crew would have to run nearly a mile uphill over the rocks to the summit of the canyon before the herd eased into a walk, and eventually halted. My 125 head or so continued crawling downhill headed for who-knows-where. All of these cattle are basically the equivalent of teenagers wandering around aimlessly in their new found country, and they needed us to quietly guide them back to the predator-safe zone of our night bedding ground around our own cow camp.

The lessons of stockmanship we had schooled in over the past 3 weeks changed the way all of us handled the situation. First of all, the beeves knew us, and were comfortable with our presence among them, both on foot and on horseback (even at night!). Second, we had learned, over and over again, the laws of pressure and release to the point of instinct and reflex. As a result, the cattle responded quickly to our attempts to settle them. And settle they did. My portion of the herd quieted, and responded to my overtures to create in them a desire to go back up the mountain. The flickering lights of the others appeared as I came up the ridge, and the two herds met, quietly, and slowly picked their way back to their newly desired end location: the night pen that they had stampeded from before midnight. Remember the first rule of stockmanship: make them want to go where you need them to go.

And so they did. We quietly closed the gate behind them, without a word from either man or beast. Within minutes, they laid down to rest. We sat together with them in the starlight, ensuring that all was well, while talking quietly among ourselves.

“I think you guys just passed the final exam of stockmanship,” I said. All 3 of them were currently in college, so I knew they could relate to that idea. All the time learning and practicing in the previous weeks had come to fulfillment in practice with dealing with this stampeded herd in some of the roughest terrain in North America. The beeves were at peace, and rested quietly as if the events of the past few hours had never happened, and it was all because the crew had moved them back in a way that did not further incite, but engendered trust in our guidance to take them back.

The next several days found us shepherding the beeves across the high ranges without incident, and here I now sit on this ridge typing this story into my phone while watching the beeves enjoying and thriving on some of the most nutrient dense wild forage on the planet. We were effectively herding them to high elevation steppe ranges that probably had never seen a bovine since bison, and the wild and robust mountain grasses, even here on the driest part of our range along the Salmon River Canyon, were waving verdant in the mountain winds in their fullest form of vegetative expression.

As the cattle graze, I watch what they select, and I observe that they are selecting for flavor. The way I know this is because I’ll sample what they eat. Salmon River wildrye, for example, tastes very much like Vermont maple syrup (dark amber, mind you). The sugar down at the node is every bit as sweet. Indian ricegrass, on the other hand, has a more nutty, yet sweet flavor. And flavor, as you know, is the telltale attribute of nutrition. It’s nutrition for the beeves and is the next link in the chain of events that allows the mineralization of volcanic soils to end up in your kitchen and eventually your plate and palate. Thank not me, or the cowboys and cowgirls who only shepherd them across this landscape. Thank the beeves, who are by nature’s own college of wild nutrition, doctoral experts in the field of foraging for the best.

Let them be your consultants.

Happy Trails.

Leave a Reply