Over the last 30 days, the killer whale (orca) known as Granny cruised silently in the shallow ocean waters along the spring swollen mouth of the mighty Columbia River at the border of Washington and Oregon.

Granny is believed to be over 100 years old, and every year, she and others return to this exact spot. She had seen Japanese submarines sharing her waters in the 1940s. In the 1960s, thousands of ships plied the same waters laden with lumber from Pacific Northwest forests, a seemingly never ending supply of timber.

Granny had witnessed the boom and bust of American industry in its taming of the wild and untracked wilderness of the Great Northwest. Silt laden waters, clouded with the volcanic soils of the Pacific Northwest told the story of overuse by humans of forest, field and stream during the extractive rush of the 20th century.

You may wonder what Granny has to do with cattle on Alderspring, but they are connected, like so many unexpected things in this wonderful complex natural world we live in.

Granny is real, and is the name given to her by those who study orcas, also called killer whales. She is one of 84 that travel between San Diego, CA to Vancouver Island, the entirety of the Southern Resident Orca population.

The Columbia’s watershed is vast, and encompasses an area that reaches from the Utah border and Wyoming in the south to far into the Canadian Rockies in the North. It seemed to humans that the natural resources never ended, and so they exploited them relentlessly to the muddy demise of the watershed’s pristine waters. But the currents of change have been recently flowing across the watershed; the water clarity had improved dramatically over the past 20 years; sight distance underwater made things easier for the whale’s aging eyes when hunting for prey.

Granny makes her annual pilgrimage here to celebrate the arrival of “June Hogs,” as they were called by local fisherman. Each March, for millennia, the largest Chinook salmon run in the world initiated with the aggregation of huge schools of salmon exceeding 15 million fish from all over the North Pacific, readying for an arduous trip that would take some of them nearly 1000 miles and 7000 feet in elevation up the mighty torrent of rapid and frothing river to their birthplace.

They would return there fighting upstream in a rush of snowmelt waters only to spawn and die. They had spent 2 years in the ocean fattening on fish to store up reserves for the journey, and the orcas were ready to capture some of the abundance before the fish left for their freshwater birthplace.

Orcas, also known as killer whales, feasting on Chinook salmon.

Orcas swim in matriarchal pods. Granny is a member of one of these pods in the Southern Resident clan of orcas. They usually can be found in Puget Sound, where whale watching boats sight them frequently. But they always return in March to the waters off the Columbia to feast. Like Granny, some individuals in the pods are very long lived.

There are only 84 in the group now that prehistorically was thought to number somewhere in the thousands. Cetacean researchers have catelogued each surviving individual and the calves they bear, carefully monitoring habits and things like fat deposition on the occasional autopsy of a beached and dead whale and collecting scat (it floats for a few minutes after expulsion) by locating it with trained Black Labrador dogs who sniff out the poop bobbing on the surface of the sea aboard boats in Puget sound.

The Chinook, or King salmon that congregate for upstream migration at the mouth of the Columbia are around 1% of what they used to be, due mostly to the construction of dams like the Grand Coulee in Oregon and Washington in the 1970s. Those dams all sported fish ladders alongside in a vain attempt to keep salmon populations intact, but the biologists of that time had not calculated the disaster of small fish getting lost on the way downstream to the ocean via blender-like turbines and flatwater pools formed behind the dams.

As a result, orca populations have suffered in the wake of reduced salmon populations. The once abundant food supply of salmon is greatly reduced. Females don’t settle when bred or lose calves. Orcas are the only animals besides humans that have the longevity to witness the dramatic decline of salmon and live or die through it.

Since the dams are a fixture in the Pacific Northwest landscape of agriculture and power generation, and it is unlikely that they get removed, attention has been shifted to enhancement of upstream habitat to recover salmon populations. It may be the only hope for the survival of the whales.

And that’s where we come in.

From my office where I write this, I can see the river. The Pahsimeroi is a flattish river, meandering serpentine down through the broad flats of our high valley, ringed by snow-clad 10,000 foot peaks. The river is fed by thousands of crystal clear springs that maintain flow throughout the year with warm water. It never freezes. It rarely floods. It is always—there. It’s a fixture that we often take for granted, because although we live by it, the slick, clear and deep waters flow silently by us, taking leave of our quiet valley for a long journey to the Pacific.

The view from the office back door. Spring begins to show in the Pahsimeroi River bottoms with the willows gaining a vibrant gold color as sap begin to run through their branches. Snow begins to recede in the lowlands, although the mountain snow will stay until midsummer.

Between the river and I, a wooden jack fence runs parallel to the river through its entire 2.5 mile journey through Alderspring Ranch. It was a have-to for us, as Caryl and I believed our cattle had no place along the fragile volcanic ash banks of the river. The fence is set a ways off the banks of the channel, usually over 200 feet. It keeps livestock from the river and the grassy meadows and willows that bound it.

I recall back 25 years ago when the first river protection fences went in. Some ranchers scoffed at the idea of protecting the river bank from cow use. Now they are more common than not, as many livestock operators in these valleys have joined partnership programs to protect streambanks, and consolidate irrigation diversion ditches to keep more water in the river and enhance habitat.

Like Granny and the other aging orcas in her pod, older folks here remember the abundance of salmon as well. They would tell me tales of how the salmon clogged the stream from bank to bank, and it looked as if one could walk on the backs of the fish across the river. There were so many that fishing poles were left behind, and other means where used to capture a few of the horde. I have been in local ranch barns and spotted rusted salmon spearing forks hanging on a nails on the wall, placed there after a year’s abundant salmon run for use the next year. But within just a few years of the dams impediments to migration, no hand would lift it from its place on the wall again.

After 20 years of near extinction, wild Chinook counts are up 500% from the 80s and 90s in the river, and instream spawning habitat use has increased. It’s because of concerted efforts by rancher landowners, Idaho Fish and Game biologists, federal biologists, conservation groups like The Nature Conservancy and Trout Unlimited.

Alderspring has been a small part of this. When we purchased this ranch 12 years ago, 40% of the spawning beds in the Pahsimeroi River was in the 2.5 miles of meandering river right here on the ranch. Above the ranch, an irrigation diversion which served a portion of our ranch and adjacent properties dewatered much of the Pahsimeroi River, and limited salmon from accessing potentially suitable habitat upstream.

We worked with numerous partners, spearheaded by the Nature Conservancy (who remain a great partner with us on some current projects), and in 2007 converted the entire irrigation system of the ranch to a water-savings system, eliminating the dewatering point. Although I’m not a fan of big machinery or technology, well-placed use of technology like this in concert with resurgent traditional skills of pasturing livestock can have immense benefits.

The results have been gratifying. While fish still use the portion of the Pahsimeroi that winds through Alderspring, they now use the area above our ranch as well. These increased opportunities for spawning sites here and in other Idaho rivers has contributed to an increase is these endangered salmon”¦and an increase for Granny as well.

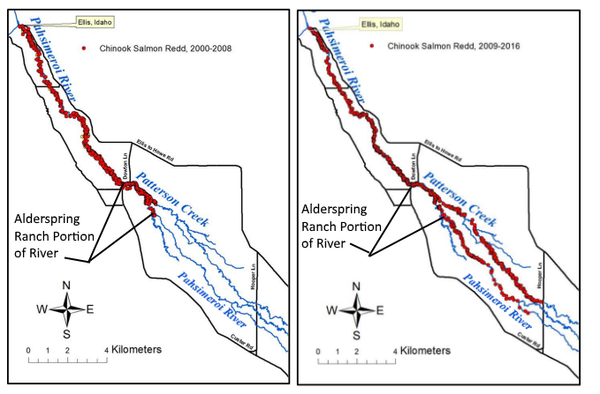

The Pahsimeroi River. Patterson Creek and the Pahsimeroi (the south long fork) meet on the ranch. The red dots show salmon spawning beds or “redds.” The dots on the Alderspring Ranch portion are so close together that they cannot be counted. 40% of all redds in the Pahsimeroi from 2000-2008 occurred on the ranch, but after 2009 fish were able to access almost twice as much of the Pahsimeroi, and also had access to much of Patterson Creek.

Granny lives far from us at the mouth of the great Columbia River, and we live here along the distant tributary banks of the Pahsimeroi in a remote mountain valley in Idaho more than 900 miles away. But we are very much connected. We own this part of the river, but since our lives are relatively short, we really are only stewards of the piece that we “own.” And we want to see it live to its fullest potential, not because there is anything to sell from it, but only because it’s there, and we are its caretakers. When we steward these parts of the landscape, effects can be far reaching: Alderspring connects with Orca.

And that is how you, dear reader and partner in wild protein, are a part of getting fresh fish delivered to Granny and kin. Our part is small, but it is satisfying to know that there is a chance that some of the Chinook she consumed over the past 100 years hatched on Alderspring. Perhaps some of them were Pahsimeroi fish that she dined on during her March 2017 Columbia feast. And despite her 100 year old age, her silky smooth and quite young looking black and white orca flesh is once again founded on a fishy form of wild protein hatched in the high Rockies.

.

Leave a Reply