Dear Friends

I have a friend, Bruce, who is a beaverologist, and that means that his specialty is beavers. He was known as sort of the go-to beaver guru in the Intermountain West. People would call him about beaver troubles (“they’re damming my culvert!” or “they’re stealing all of my irrigation water!”), begging him to relocate them to somewhere in the vast “big open”—the wide wild places of the West, on US Forest Service or BLM lands. After all, in places like Custer and Lemhi County, where we live and work, public, or government land amounts to over 90% of our land base.

In this photo, as far as the eye can see, is public land.

As you probably figured out, there’s no such thing as a “beaverologist.” After all, who would care that much for a double buck toothed flat-tailed rodent whose top speed is somewhere on the order of 6 miles an hour? Mr. Beav is among the lowest on the food-chain pole, and has the distinction to the top “dogs” such as wolf, coyote, mountain lion and bear of being considered a sort of cream puff to be relished.

That’s exactly what the rodent (castor canadensis) is in the open country of the Sagebrush Ocean. If spotted by one of those predators on their food finding forays, they must think that certainly their ‘dessert bar’ has come in. Trot over and consume. Maybe even a canine grin while doing it.

Bucky certainly has found equivalent and even greater evil enemies in Homo sapiens. I’ve eaten beaver tail (not bad, with the right seasonings, by the way), but it wasn’t culinary killing that wiped the rodent out in vast areas of the west starting 175 years ago. California, with its abundant waterways, was home to millions prior to the 1849 gold rush. By 1950, there was not a single known beaver in the state.

The hunt for beaver started much earlier than that. It’s almost embarrassing to be a human and pronounce the reason for extirpation, but I’ll tell you anyway (easier to do in writing).

It was hats. Men’s hats, to be specific. Top hats, bowlers, fedoras and Stetsons all shared the same origin: beaver fur—actually hair. The density achieved in the weave of beaver fiber is unparalleled, even today. Yep. Hats, men’s hats, specifically (rest easy, ladies, as this article won’t talk about fur coats) nearly wiped out the castor canadensis. Near wars were fought over territories. Trapping rights even became combative, and bloodshed was not unusual.

A beaver fur hat from the late 1800s.

Fact: It was vanity that killed beavers. Perhaps you say “so what?” It’s a confounded rodent, after all. Relative to rat and other vermin. Parasites on human habitation.

Back to Bruce. He saw it differently. You see, Bruce was actually an ‘ologist’ by training on another order. Bruce was an Ichthyologist. In more common parlance, he was a fisheries biologist. He was trained in the knowledge and management of trout, that cold and oxygenated water resident of nearly all Rocky Mountain streams and rivers.

Back in the 1970s and 80s, there were few fish specialists making the connection that without beavers, there was often a shortage of fish. Beavers slowly came to a place of unlikely recognition as a “keystone” species. In ecology, a “keystone” species is named for the top rock that was laid in the crest of a Roman arch—the final stone that provided critical support and tension to hold the aggregation of rock together. A keystone species is often a top level predator (for example, the wolf), but it can also be a species that has large and irreplaceable effects on ecosystem functions. In the West, the beaver historically filled that role. Beavers expand watercourses, keep streamflow sustained during even droughty summers, create shade and water cooling by depth and woody plant recruitment, and filter out sediment from creeks.

This is a network of old beaver dams on our rangeland photographed before beavers repopulated our range. These ponds had been abandoned and inactive for several years, but even so, you can see that long after the beavers left this is still an incredible source of biodiversity and wildlife habitat.

Fish need beavers. So do a host of other plants and animals. Avian life doubles in scope and scale where beavers set up residence. Even their nemesis, bear and cougar, relish the dense cover. They lie in wait in the cool shade until Domino’s delivers an elk, deer or pronghorn pizza.

In ecological lingo, not only are beavers a keystone, but they initiate what is called a ‘trophic cascade.’ The foundational presence of their life form initiates a cascading effect of ecological “if-then” statements for nearly every other form of life in plants and animals to find a niche.

In other words, the cascade can go like this: Beaver builds dam; the now-flooded area of the creek hydrates soils; aspens send up sprouts (being stimulated to sprout after beaver cuts off stems for dams) for new trees in adjacent formerly dry-ground sagebrush areas; birds build nests in the aspens then feed their young from the abundant bugs that hatch from nymphs in the pond water; trout survive better in the cascading-over-the-dam-now-more-oxygenated water and pick up now plentiful insect nymphs spilling over the dam; black bear finds easy fishing at the foot of the dam where fish congregate; ospreys and bald eagles swoop in to pick off fish rising in the pond impoundment that is now open enough (the trees and brush died and got cut off to build dams) to swoop down in; ducks land in ponds to build nests; cougars eat ducks.

There’s so much more. And beavers, that humble and fairly defenseless rodent, are at the root of it all. Bruce figured this out. And he filled a niche in biologists of that day, and stood firm in defense of beaver. In the words of Malcolm Gladwell, Bruce was an outlier.

When we started grazing the big country of 70 square miles of Hat Creek, there were no beavers despite the fact that there were 55 miles of perennial creeks tumbling down through the dissected valleys and ridges of that expansive country. Caryl and I figured there soon would be because we began intensively riding herd on cattle that visited creeks. We were on horseback up there for as much as 5 days a week. For most of those days, we had our young girls (under the age of 12 on their own horses) pushing through brush and thick timber, trying to find cows). The problem was that in that big landscape, we would find somewhere on the order of 50 head in a given day out of 300 spread across the range.

Here’s Tim, an Alderspring employee about 15 years ago (he now runs a grass fed beef ranch, Stand Fast Beef, in New York). Tim is clearing cows out of this creek and bringing them to the uplands…which we did often, but even while we’d find and clear 50 from a creek in a given day, 250 would be in creeks elsewhere on the range.

The other 250 were behaving badly; of that we were certain. Cows, from force of habit, without our influence, will fall victim to the siren song of the two “Gs:” Green (grass) and gravity. We would invariably find creeks degraded by two things resulting from cow visitation: bank trampling and overgrazing.

Amid the sagebrush sea, that green patch looks mighty tempting to a cow.

We are both trained ecologists. Caryl has a doctorate in plant ecology and was working at the time on a book that described every riparian (water related) habitat and plant in the intermountain west. We had long known cows were absolutely destructive to the thousands of miles of creek, lake and spring in the west, and had hoped that we could make a difference while running our cows on the range. No major changes were happening in our riparian systems. We had one colony of beavers appear for a few years. We celebrated! Then they disappeared again, and our riparian areas continued to show no changes.

We were stuck.

As humans, we can sometimes choose to stay stuck. Somehow, it almost seems like we relish the pain and misery, drowning so much that we think it is hopeless, and it takes to much energy to devise a way out and change the situation.

But then, an influencer forces a hand. Perhaps it is a podcast you’ve heard, or a newfound friend offers you a different point of view. And perhaps out of hope or desperation, you reach out of your comfort zone to grab what could (or might not be) a lifeline.

It can be risky.

Occasionally, the influencer is 100% perceived as your arch-enemy. And that is exactly what our influencer was.

It was a wolf.

Wolf packs had been slowly creeping into our grazing territory, and it just so happens that organic grass fed beef was a preferred food choice for Canis lupus. The only problem was that they weren’t ordering through our normal Alderspring webstore channels.

They just took them. It was slow at first, but then, in just one year, we were down by $35,000 in lost cattle. The grazing range had officially become economically unsustainable.

We had three choices; they were: 1. Quit (initially, this was the preferred option. Riding as much as we had was wearing us out, and the ranch was a marginal enterprise to begin with); 2. Kill all the wolves (this is what all of our neighbors were trying to do—it is legal); and 3. Find a way to coexist with the big canids.

Problems: Number one wasn’t working out. Caryl and I are pureblood descendants of Frisians—some of the most stubborn people on earth (they literally pushed the sea back with dikes to create farmland). Number two wasn’t really consistent with our ecological bent. We had spent a lot of time with wolves in the Canadian north, and didn’t feel we needed to kill them. Wolves are also a difficult animal to hunt: they are smart and wary of humans, and even killing one wolf can be an undertaking. Besides, the winds of politics were changing across the West. It may not be legal to terminate wolves that kill livestock forever and didn’t seem like a long-term solution.

To coexist, we knew what we had to do. We had to live with the cattle. It was by no means a new idea—instead, it was a re-inventing of an ancient one. Herding and shepherding livestock was one of the oldest professions, and those before shared some of the same reasons to do it that we had.

The Bible talks of shepherds watching their flocks by night…herding livestock is a thousands-of-years old practice. American cowboys and shepherds used to do it too, until the advent of barbed wire on rangelands made it unnecessary to live with the herd in order to keep cattle together.

First, they herded to keep their herds safe from predators. Second, they took them to good grazing. Third, they kept their animals safe from theft (rustlers). Fourth, they brought them to water. Caryl and I shared those ideals, but with an ecological twist. We wanted to keep them from water, in a sense. Those 55 miles of trout streams (or potentially trout bearing) would be off limits. We would devise “safe” water zones, where the cattle could drink their fill without ever trashing and defecating on the banks of a creek.

A friend of ours, Mark Davidson, at the Nature Conservancy carefully considered the idea, and thought that he could help us with some funding for a few years while we learned the “Art and Science of Shepherding.” I have that in quotes because a [now] friend of mine, Dr. Fred Provenza co-authored a book of that name which turned out to be foundational in how we considered this new idea.

The crew unsaddling in front of the cook tent at the end of the day.

You might say that cowboys still ride horseback “punching,” “driving,” or “pushing” cows in the west today. Completely true—and they are dang good at it, as we had become. But here’s where the nuance comes in: when cattle are being driven, they lose weight. Today’s cowboys often “drive” cattle to a new pasture (expecting to have cattle lose some weight on the drive), then leave them in the pasture to graze and gain weight until the next move. We needed them to gain weight while we moved them, because we are in the ranching business. It is about pounds. We grow beef cattle to USDA choice on grass to sell to our customers online. So we needed to get our head around a stockmanship that would encourage the beeves to eat (not lose weight!) as we herded them in a unit to keep them safe from predation.

Here, range rider Jed is not actively pushing. Instead he’s just a fence, parked in this spot for a moment and keeping the herd together and pointed to the right of the frame. If a steer gets an idea and tries to quit the herd or pass Jed’s invisible fence, Jed will turn it back into the herd or send his dog after it. When we are intentional about training them, the cattle learn pretty quickly to recognize a placed rider as a sort of fence. When the herd moves on, Jed will move his horse on.

Why would they be safe? It’s because the top-dog on the food chain knows he is not truly the top dog. Wolves are smart—they know humans can be formidable opponents out there in the wild. They are wise that humans may be up to no good, and keep their distance. So the answer to our crisis could easily be answered by simply moving across the country, and letting the wolf know through our human scent and presence that we are staking temporary claim on the land under our beeves’ feet.

And so, we began camping with cattle. For the first years, it was just a few employees, myself and the family. It was the school of hard knocks. We had long days, and complete wrecks when we’d lose control of the herd. But we started to learn the art and science. We got out of the mindset of “pushing” cattle. Instead we learned that we could often place our horse in exactly the right spot and simply stand there, watching the wave of cattle move and turn exactly as we wanted them to.

We weren’t sure how it would go with the wolves at first (would they still bother our cattle?). But the wolf predation ended immediately. We saw plenty of sign of our canine friends and we’d hear them at night sometimes. Once, two crew members spotted one on a distant hillside, loping away from the herd and riders, glancing back occasionally with some interest in what we were doing. But they never came near. And the creeks saw no more cattle use; we simply piped and pumped water from the creeks to portable stock tanks.

A temporary stock tank full of water pumped from the nearby stream (there is a fish screen over the hose to prevent us from pumping any fish into the line). Cattle get a clean drink unmuddied by hoof traffic, stream remains completely untouched by bovine.

And the range rebounded immediately. We discovered that nature is a strong force.

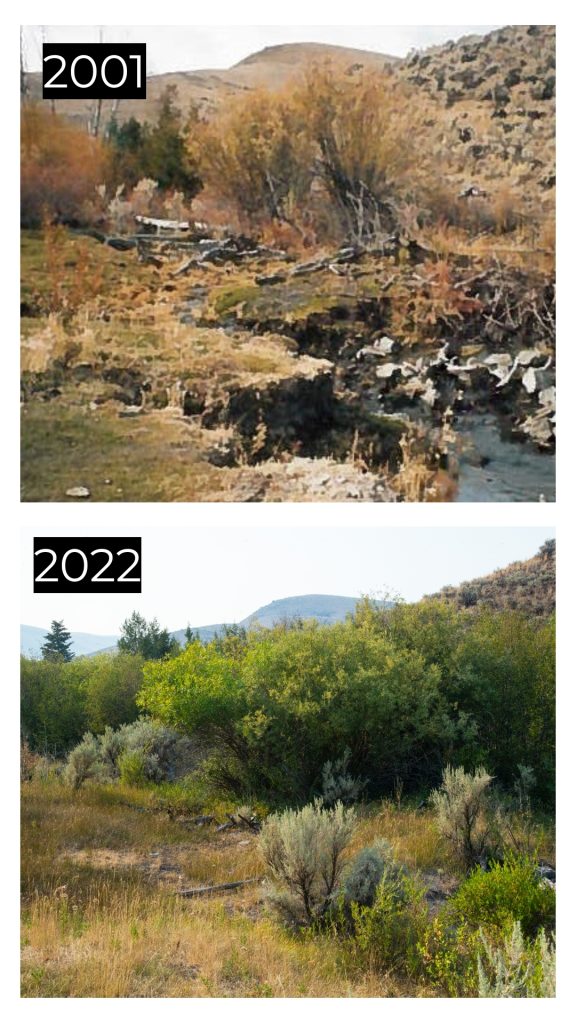

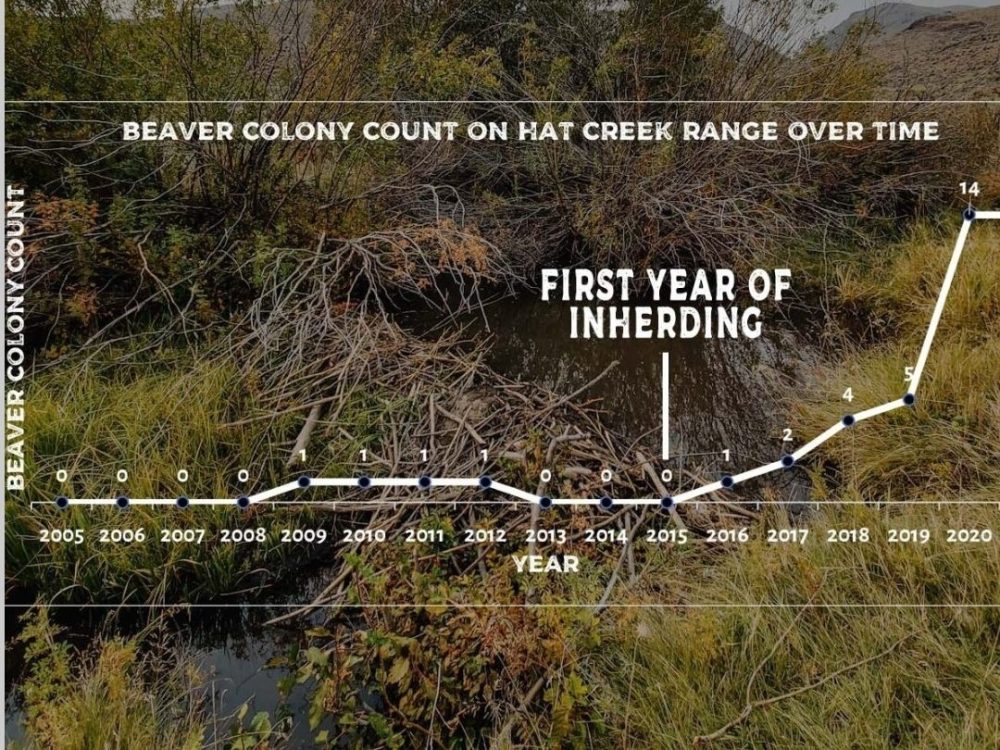

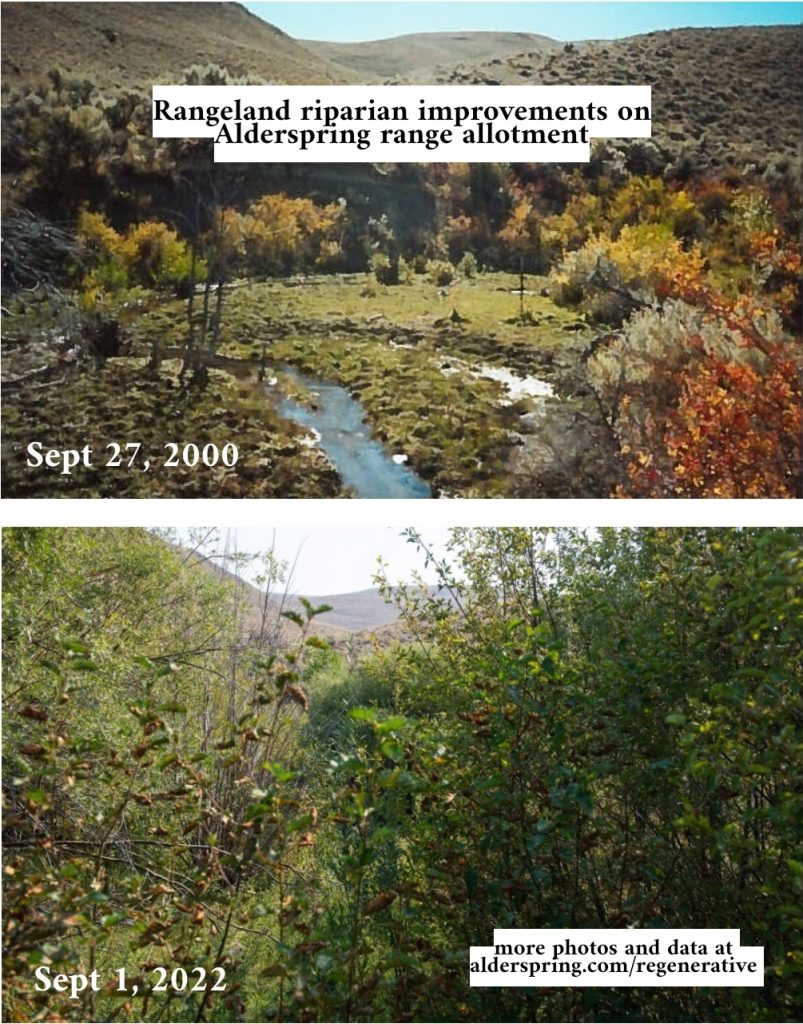

Most of the changes you see here happened just in the years after 2015.

Beavers showed up the year after we started herding and camping with the cattle. It was on Little Hat Creek in 2016. I spotted fresh dams and a beaver while horseback running recon for the next grass we would graze. I turned ‘Missy,’ my Morgan mare loose to graze, and belly-crawled my way to the new pond. He or she was a small beaver in this green ribbon of creek in the middle of a massive swell of the Sagebrush Ocean. I pondered how he got there, thinking perhaps he was dropped in by parachute (this technique was successfully experimented with right here in Idaho back in the 1980s to reintroduce the rodent to remote areas of Idaho).

But I knew the truth. He walked over literal miles of desert sage—perhaps as much as 12 or 15 miles. Here’s where it gets interesting. Beaver researchers have found that the humble rodent live in loosely arranged social colonies up and down creeks. It turns out that one—a sort of grandfatherly patriarch will sometimes take long scouting missions to find new habitat in case theirs becomes too crowded or no longer suitable. He’ll then return (if not now a nicely digested cream puff to a wolf) to his family or tribe and somehow “tell” them where the good habitat is (microphones have been inserted into beaver lodges and recorded their curious murmurings to each other—Uncle Bob telling stories again?).

A stream wends its way through the bottom of this canyon (we are camped alongside it with some temporary stock tanks full of water pumped from the stream and no access to the stream for the cattle). To reach this spot, a beaver would have to cross miles of these exposed sagebrush hills…and yet somehow, they have.

And so, a colony branches out at absolutely incredible against-all-odds risk. Usually a couple of beavers will go out together (male and female). This turns out to be the most important factor of beaver re-introduction success, by the way. If humans are trying to re-instate beavers to creeks, they new colony will absolutely not stay if a member of the opposite sex is not there (side note: it is gender identification that becomes difficult. All of the beaver’s “parts” are inside. The most successful beaver gender identification specialists can pull off the identification by smell of a sample of fluid from that opening. A wonderful job, I might add. Little wonder that I’ve never met one of these experts! There can’t be many of them.)

After these first two individuals found home, we began to discover more over the next years. Pretty soon, most of our creeks had beaver colonies in them. Now, we estimate that there are 85 beavers living on the Hat Creek Ranges.

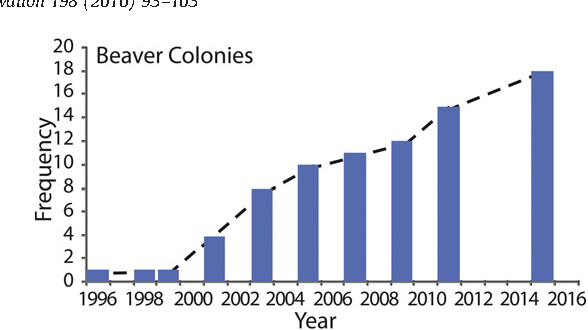

This graph comes from a beaver count done in Yellowstone Ntnl Park. The Alderspring beaver graph looks quite similar, except our increase went from 0 in 2015 to 14 colonies at our last count in 2020 (we know exponentially more have appeared since 2020 but we haven’t done a precise count). Interestingly, Yellowstone’s increase in beaver colonies was also driven by the wolf: elk were overgrazing Yellowstone riparian areas in the same way cattle overgraze many Western range riparians (elk, too, are lured by the two Gs without an outside factor “herding” them). Wolves were reintroduced to “herd” elk from riparians and control populations. We think the reason Alderspring’s beaver colony increase was almost 3x faster is because we completely ceased any grazing in riparians, while wolves “herding” the elk didn’t result in a total end to elk riparian grazing. Riparian overgrazing is still an issue in Yellowstone that hasn’t completely ended with the reintroduction of wolves (in fact, we’ve had park managers from Yellowstone ask us about our herding methods as a way to manage bison that are overgrazing Yellostone riparians).

But something kept nagging at me. Our creeks weren’t completely denuded of aspen trees and willow shrubs before we started living with our black Angus beeves, and everyone knows that without one or both of these woody plants, beaver recolonization wouldn’t happen. We all knew the beavers literally ate the wood and needed it for their extensive construction projects. But we had plenty of aspen and willow even pre “living with cows.” All of the beaver ‘experts’ I had asked about it stated that all I needed to see beaver return was the triad of rodent success: aspen, willow and water. Those were present. But the recolonization never happened until we changed how we grazed. What was the defining agent that gave them the red carpet to recolonize?

It was a late summer day 2 years back up on our Little Hat Creek ranch that an idea began to precipitate in my mind. We have a small private inholding in the middle of the 46,000 acres of range—a place for some loading corrals at the end of a decent dirt road, and, of course, Little Hat Creek itself, the sinuous centerpiece of the 1800s ranch that made for lifeblood of the little ranch in the middle of the Idaho outback.

Beavers had returned to the ranch, too, after a many-years absence, and over the few years watching their return, I think I might have imbibed some beaver blood of my own. I couldn’t stop obsessing about them and their keystone effects on our rangeland ecosystem. I was seeing fish and birds like I’d never seen before. Even the endangered sage grouse appeared to be returning. On one trip horseback down Little Hat’s ancient trails (indigenous people used it for millennia before we did), I counted an unprecedented 46 birds.

I was on foot today, going to check on the status of recent dam construction on the ranch. I was in no way their project supervisor, but I was concerned about the inhabitants of the creek ecosystem. Everything from beavers to birds and frogs to fish were in jeopardy this year due the drought effects on Little Hat’s streamflow (that summer two years ago was the worst drought seen in our area in 127 years).

As I came up to the latest beaver impoundments, I was relieved. The dams were secure, and water was stored. What that meant was that this portion of the creek would never go dry, and they had established a sort of aquatic refuge for all of the creek inhabitants to come to. The ponds were large, and they would provide a long-lasting sustained flow downstream that would maintain life.

But then, I noticed a problem. Someone, or something had been grazing along the creek. All of the Nebraska sedge and Baltic rush had been eaten. Frustration welled up in me as a first response. Several of my twenty-something daughters were on the range with the cattle this week, and apparently, they had lost control of the herd, and some of their recalcitrant beeves had found their way to the creek, following those two Gs before the crew regathered them.

Two of those 20-somethings, Annie and Linnaea, planning the day’s grazing using a Google map on a cell phone. Glenn assumed that those plans went awry and they lost track of a few head of cattle that then followed the 2 Gs of unattended bovines.

It was not OK. In my mind’s eye, prehistoric creeks were never subjected to extensive grazing, except by moose. Elk, deer, bison and sheep all were wise to the fact that big predators like lions and bears loved the thick cover of creek. If we were to bring habitat back, our own grazers needed to stay out.

I crawled down along the beaver dam and looked for cow tracks. There was fresh mud on the earthworks of the dam, and new chews of the aspen and willow sticks that made the matrix. Beaver tracks made round impressions in the muck. I looked everywhere for sign and track of cow.

And I couldn’t find one. Not even an elk or deer track penetrated the black muck under the sedges and rushes. Only beaver soft prints and their telltale tail drag track.

And then I wondered if my rodent friends were grazers. Like cows, they had to have a ton of bacteria in their guts to digest cellulose; after all, they could eat aspen and willow bark. I always thought that was what they ate. It’s what nearly every book and bragging beaver authority stated. They did store sticks in dam impoundments in the winter, but it looked to me that green pastures were the rule of repast in the summer.

That night, I raided the online literature. Thankfully, I have a PhD bride that has access to scientific literature databases. And I found several articles, obscure though they were, describing the graminiod grazing habit of Castor canadensis in riparian ecosystems. It turned out that grasses and forbs are critical for winter fat accumulation, fecundity (successfully breeding and raising kits) and even lactation.

What that meant was that the riparian and wetland grasslands had to be intact before beavers could return. It wasn’t just about the woody aspens and willows. It was about winter fat deposition from grasses, just like our beef cattle. If their green pastures were eaten off by a bovine, beaver would be out of luck, and move on to greener ones.

Middle Fork of Hat Creek, one of the streams on our range photographed by Range Rider Bryce about a month ago. Bryce was horseback behind the herd high on a hillside when he took this photo of the network of beaver ponds below. The crew had started the day’s graze far on the direct opposite side of the stream in the valley below and had to cross to move to a new camp. They went to great pains to avoid Beaverland here (also home to spawning trout at the time), circling around about a mile upstream and through dense timber in order to cross on a bridge. Not a bovine hoof touched the stream.

It’s why if we want the keystone to return to the arch of ecosystem, we first have to control our cows. When we did, it made all the difference.

I saw Bruce in the hardware store last week. Retired now for ten years, he was finding some plumbing parts for a leaky sink at home. I excitedly mentioned my beaver grazing grass discovery. “Bruce, these beavers need good grazing of grasses to colonize and be successful! I had no idea. I thought it was just aspen and willow!”

Another customer holding a white sink elbow turned awkwardly away, avoiding eye contact as I spoke, and slowly made their way to the next aisle.

Bruce’s wizened and gray-bearded mug slowy smiled, and almost imperceptibly nodded.

The beaverologist already knew.

Happy trails to you all.

Glenn

Julene Jacobsen

This was a very interesting and inspiring story. It caused me to think about the many things we don’t know in our wonderful world. I am so glad that you are educating others who will then follow in your footsteps to make a better place for humans and animals alike. Thank you so much for providing our family with such nutritious food.

Glenn Elzinga

We often feel that we have only scratched the surface of understanding how everything works out there…and how we fit in!

Shirley

What makes your stories so interesting and inspiring is your polished command of the English language. Your stories can make me smile, cry or laugh and can make me feel like I’m right there sheparding with all of you! Keep the great stories coming. And do consider writing a book someday, an anthology of your stories 🤗

Glenn Elzinga

Hi Shirley,

Thank you as always for reading and for the kind words! And Glenn actually is working on a book that compiles many of his stories together into a bigger picture…but finding the time to work on it is the problem!

-Linnaea (one of the daughters)

Marcia Boettcher

I’ve got ADD. It takes something marvelously written to hold my attention for the length of your stories! You are truly gifted and blessed in many ways! Thanks for the respite!â¤ï¸ðŸ™

Glenn Elzinga

Thank you so much for reading, Marcia! Glad it kept you interested! 🙂

Curt

Great report on you success. It would have amazing to see that country in the early 1800s.

Glenn Elzinga

We often wish we could have seen it then, Curt! We sometimes find traces of what it looked like, or read old settler accounts that describe “tall, stirrup-high grass” as far as the eye could see. In some areas we actually see some of that stirrup-high grass coming back and can begin to picture what it must have looked like.

MICHELLE

So interesting and informative! There is so much to learn about this world we live in and I thank you for sharing. We are all so interconnected…plants, animals, humans…it was masterfully planned.

Glenn Elzinga

It certainly is, Michelle! It’s actually beautiful the way it all fits together.

Jeff Zaremsky

Great story once again.

There is a beaverologist who watched a family of beavers for more than 18 years and noticed this particular beaver colony were out and about swimming, working, eating, playing, building 6 days a week, but each week they totally rested one day. Every week it was the same exact day, and each week it was a total rest, not even leaving the den. This continued, week after, week month after month, year after year.

Here is a short 3 minute video of it. There is a longer version also.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=49T5unQEIbY

Leo Younger

Learning from each story is the reason to read them. We need knowledge, understanding and wisdom. Thank you for providing in many ways.

Krista Willmorth

Another amazing feels-like-I’m-there article Glenn. Thank you for not only doing the (really hard) work, but for teaching and sharing as well. We’re all better for it. I’ll be sharing this article quite a bit.

Tim grant

That is a great recounting of how the beaver returned to thrive on Alderspring! You’re a good shepherd of the whole ecosystem really with the activity and decisions you’re making. I need to get back out there to see it again and how it’s changed.

Glenn Elzinga

Tim, come back anytime! We’d love to have you all come ride with us for a few days.