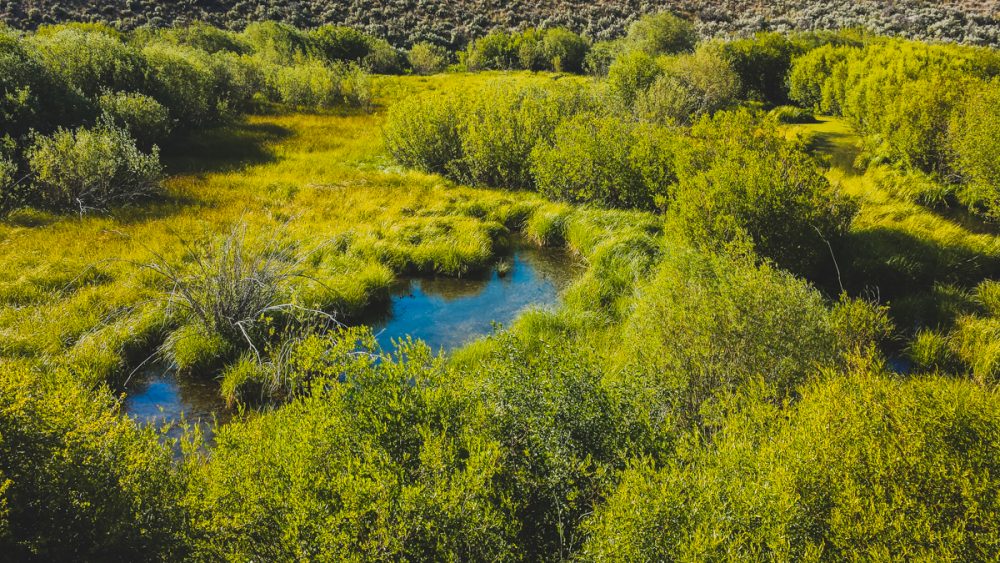

Beaver camp, July 2019. We call it that because there were at least two colonies of beavers there, thriving in the waters of upper Little Hat Creek, just a few hundred meters from where we were living as well, in a five tented temporary settlement of cowhands and horses, high in the backcountry at the foot of Table Mountain.

They didn’t seem to mind our presence; certainly, they continued their meanderings across dam and pond, maintaining elaborate structures that guarantee safety, security, and food abundance over the four seasons of Idaho.

I watched as they felled small and large tree and shrub, very intentionally towing them with their long-toothed mouths, then chewing and severing them into manageable units, and incorporating them into a haphazard looking mud and wood thatch matrix that would prove impermeable to even the smallest flow of water.

I would sneak out of camp and crawl across grass and sage to witness the long-toothed and great rodents ply their waters that they alone created with engineering prowess unmatched even by humans; if we had been given the same native materials of aspen, willow, and mud, we would have little success with such endeavors.

I couldn’t help but respect them.

They had returned to Hat Creek starting only 5 years ago, traveling across vast areas of sage to recolonize their lost stronghold there. I knew it was a lost civilization of Beaver because I could see the evidence of their construction—perhaps even 60 years prior—ancient (for beaver) dam berms, now breached by creek, but still slowing the flow of waters downstream. But we hadn’t seen evidence of beaver for 10 years—until the first colony showed up in 2016 on the 55 miles of creek on the Hat Creek ranges.

We always thought it had to do with creating habitat for them in the form of woody plants; when we completely changed our grazing patterns in 2014 and 15 to that of a herding practice, we were then finally able to keep cattle completely out of the wet stream areas by preventing access with our crews on horseback. In short, we went from our cattle accessing 38 miles of stream to just under 1000 meters in two years.

And the results were astounding. Woody plants like aspen and willow literally took off after being browsed by hungry bovines for over one hundred continuous grazing years.

And shortly afterwards, the beavers came. ‘If you build it, they will come’, we thought. It was what all the scientific literature stated: provide enough woodies provide food and construction materials, and beavers will come back.

Who told them that the habitat came back, we will never know. Some beaver observers postulate that “scout” beavers would venture out of their home ranges and travel across vast areas in search of new lands. Often, they are patriarchs—grandfathers and great-grandfathers, who then lead their offspring families in pioneering ventures through hostile territories occupied by the likes of wolves, cougars, coyotes, and bears.

Beavers are mere fatty little whipped cream puffs to them. Average top pursuit speed of those top-of the food chainers: 32 mph. Average speed of patriarch beaver and his wagon-train pioneer family: 6 mph at the top end.

Literally, dead meat if found.

So, against all odds, the beavers came to Hat Creek.

Because we built it, right? I mean the woody plants that they need, right? Perfect welcoming mat for the Big Beav and his fam, right?

Wrong. Kind of.

Beaver Camp, July 2021. The camp is uninhabited this year. We humans decided not to even graze the vast areas around beaver camp this summer. It is a complete rest area from grazing. It’s not a small area. That and the Bear Basin area, just adjacent to it, were selected for complete rest from grazing this year by Caryl, the girls and I to simply give the plants and upland habitat a break from cows, just like prehistorically, when bison and herds of native sheep and elk or deer just didn’t happen to range into an area. Nature often gave breaks to country.

In all, we left about 18,000 acres of grass ungrazed, despite it being a drought year and us running more cattle than ever (nearly 450 this summer) on the Hat Creek Country. I think we were finally seeing the benefits of the adaptive stewardship grazing we were practicing over the 70 square miles of country.

But I was checking it out this early July. I wanted to see specifically how the beaver were doing in Beaver Camp. I remembered the location of their dams and lodges well. And so, I took my Honda XR 200 dirtbike up there; it was a long and tortuous road of many miles (too many for a horse for one day) and brutal in a pickup truck.

I parked the bike in the tall brush along a copse of verdant aspens along the creek. They rustled, rounded, silver dollar sized leaves trembling, nearly spinning in the pattern that gave them their full common name—the “quaking” aspen. It was even in their scientific name: Populus tremuloides; translated as the “trembling poplar.”

The tree was a favorite of mine, and of beavers it turns out. They love the easily chewed wood for dam building and lodge construction; it could be easily carved by their massive red incisors, and handily cut. In addition, the young growth made for excellent winter forage when intentionally placed for safe keeping in the mud bottom of their nearby pond.

And so, I walked from dam to dam, hoping to find a fresh chew of our rodent friends, the keepers of streams, holders of water, creators of fish habitat, the bringers of birds, the flash flood controllers, the planters of more trees, the cultivators of meadows, and even the massively efficient capturers of atmospheric carbon.

You can see why they are important.

And I walked quietly, waiting with bated breath to hear the ker-splash of beaver tail slapping the water of said ponds of their own design, alarming all—not only their kin-rodents—but also all else living in the habitat zone that a predator was on the prowl.

Said predator was me in this case. And I was OK with it. Especially since I was guilty as charged. It turns out that my species is responsible for the near extirpation of Castor canadensis (science for North American beaver) from the face of the North American continent. For hats. No kidding. Hats. Watch Pride and Prejudice sometime. Those black Top Hats that were the rage in pre to post Victorian Europe.

So, the slap of water would be appropriate. At least it wasn’t in my face.

But I never heard it. Instead, ducks flushed, one after another. I startled two elk from just 25 feet away. Fresh bear tracks punctuated the mud. Birds sung their excited songs of joy mixed with alarm. And then I heard an unusual sound in beaverland.

A trickle of water. I crashed through bough and bush until I found it. A small gap in the dam, about 3 inches deep, and 1 foot wide. It had been running there for a while, it seemed; perhaps since high water with snowmelt flows breached the dam and washed beaver mud and stick away.

Studies show that beavers will respond to an irresistible pull of the sound of flowing water immediately. Researchers placed speakers with trickling sounds along dams only to catch on camera desperate beavers searching for the water-leaking sources of sounds.

And no beaver had come to the rescue of this water, being lost to gravity. After searching for hours, I found no fresh signs of beaver. Lodge had no hole in it; no bear ripped it asunder. They were simply gone. Perhaps cream puffs to a wolf or bear? Perhaps. But the question persisted in me for all the weeks thereafter, until this last week, I thought of something out of my beaver box of thought.

I asked Caryl, my wife, PhD plant ecologist, and overall observer with me of animals and their habitats. “What proportion of a beaver’s summertime food is not wood—in other words, is in graminoids (grasses) and other soft forbs?” We both believed it was insignificant because nearly all the literature we had read suggested that woody plants were what Castor fed on.

And so, we entered the hallowed halls of a library, called Google, and begin to come across pieces of the puzzle. Indeed, it turns out, some beaver-ologists who did dietary research stated that the beaver’s diet was quite like a cow’s during the green season. They ate a lot of grass during the summer months.

They grazed. Some scientists surmised that in summer, grass was as much as 90% of their fare.

And then, a piece of the puzzle fell into place.

Ben, a neighboring rancher and friend, came down with cancer last summer. Pancreatic. It was a disaster. It completely took the wind out of nearly all those living in our humble Pahsimeroi Valley for much of the summer. Ben was just a great guy and was there for so many folks who live here.

I had just seen him at the beginning of last summer (2020), and then, just a few weeks later, he was in cancer treatment. It was an incredibly aggressive form, so much that it took him out. By July, Ben was really compromised by the disease; by October, he was gone.

His family and friends surrounded him as he suffered illness and eventually passed. What that meant was that the cattle he owned on the adjacent to our grazing country-Morgan Creek missed his and his family’s expert hands in riding horseback to keep them progressing through the country as they normally did. We rarely saw Morgan Creek Cattle on the Hat Creek side.

But that year was different. Before we knew it, we had over 80 pairs of black Angus cattle on our side; many ended up in the Beaver camp area weeks before we got there to herd them off. We just didn’t know, and neither did our neighbors.

The unknowing cows didn’t have any use for the aspen and willows that had grown up in the creek; but they did inhale the abundant grasses we had regenerated all up and down the creek. In the several weeks they had to live in there until we found them, they ate the grasses to the ground.

There was nothing left for the beavers, I think.

And so, the rodentile nomads packed their wagons and moved on. To greener pastures. Where? I have not found them yet. Hopefully, they stayed in Hat Creek. It’s rare that I see even half of the 55 miles of creek each year. But I bet they are there somewhere.

And so, we’ve learned a new thing, I think, through that unfortunate series of events. Beavers, it seems need more than aspens. They like grass, like cattle, and most likely need it for sustenance during the summer.

The problem is that we need them to set things right. For us to restore the health of our lands, we need partners like beavers, who with one stick, one bit of mud at a time, change the earth. And eventually, through their 24/7 persistence, like that of an ant, reinstate nature’s course.

And we humans affect it all, whether we know it or not. As you likely figured out, I have very little blame I assign for the state of our wild lands. Sure, it’s humans who, often through their hubris, upset the dynamic equilibrium that nature runs in. Part of it is because we are ignorant, but don’t lose hope. There is much to learn. And we are still learning.

I’m so glad nature is a patient teacher.

Happy Trails.

-Glenn

Deb Olsen

Wonderful story! Yes God has made every little thing on earth for a reason and we can all coexist if we don’t get greedy. Man unfortunately has messed with Mother Nature on so many levels that we too may be endangered some day. I often think of how each thing on earth was made for some reason no matter how small it is and the balance can throw everything off if just thing is taken out of the equation. I respect the fact that you all work to put things back into perspective and slowly heal the damage that has been done by generations of neglect and ignorance.

Deb Olsen

Wonderful story! Yes God has made every little thing on earth for a reason and we can all coexist if we don’t get greedy. Man unfortunately has messed with Mother Nature on so many levels that we too may be endangered some day. I often think of how each thing on earth was made for some reason no matter how small it is and the balance can throw everything off if just one thing is taken out of the equation. I respect the fact that you all work to put things back into perspective and slowly heal the damage that has been done by generations of neglect and ignorance.

Curt Gesch

I’ve always read that beavers love willows. In our region (central British Columbia), they love willows for dam building and lodge building but don’t eat them much. They love the quakies best of all.

I have been on a lake with a huge beaver lodge and only spruce/pine forests surrounding it (perhaps the beavers ate all the deciduous trees out of existence?). But they live on lily pads, roots, various other pond plants, said the biologist.

Curt Gesch

I’ve always read that beavers love willows. In our region (central British Columbia), they love willows for dam building and lodge building but don’t eat them much. They love the quakies best of all.

I have been on a lake with a huge beaver lodge and only spruce/pine forests surrounding it (perhaps the beavers ate all the deciduous trees out of existence?). But they live on lily pads, roots, various other pond plants, said the biologist.

Natalie

Their modification of the environment reminds me of what happened in Yellowstone when the wolves returned and culled excess numbers of deer/elk, thereby improving the overgrazed stream banks. Not unlike what you do with your hot wires as you protect your watercourses.

I was in Alaska decades ago and while on a walk near Denali, I came across a large beaver lodge. I climbed atop, admiring their sturdy handiwork, and brought back a small piece of beaver-chewed wood with its teeth marks.

A couple of months ago I read a story about a place wherein lots of beavers had been shot, and all I could say was, why?