It was in the late 1980’s and Caryl and I were in the Midwest so Caryl could work on her Ph.D. It was late fall, and I was looking for a little harvesting work in the corn belt while she finished up her research and dissertation. Now, Midwestern October weather wasn’t exactly what we had gotten used to living in Idaho. Our balmy Rocky Mountain blue skies were hard to exchange for the slate gray that the Great Lakes States often had in the fall.

But that slate sky was the reason the corn belt was there; it meant continual moisture that watered the seemingly endless corn and soybean fields. Just 200 years ago, before westward expansion, these flat fields were endless meadows of tallgrass prairie. It was a literal sea of grass, and when the wind blew over it, it would wave much like the ocean swells that buoyed the immigrants who first colonized the new world aboard square-rigged sailing vessels.

This new ocean would envelop pioneer wagons rather than those ships, and the heads of a big bluestem grass stand could block the horizon from the view of a man on horseback. Men soon found that the untouched prairie grass and the deep rich sod that mirrored the abundant grass above would yield first to fire and then the plow. To the agricultural dreaming immigrants that came to the New World, they had found a paradise. There was nothing that even came close on the European continent, and the rocks and forests of New England and Appalachia paled in comparison to the 60 feet of black prairie topsoil on flat ground that beckoned to their plows.

And plow they did. All of it. Swamps and lakes were drained, rivers straightened, and fields leveled. It was the end of North America’s perfect symbiosis of bovine and grassland; nearly 50 million bison were exterminated, and the prairie grasses were marginalized to railway and road right of ways and the few hills with soils too thin to benefit from the plow. My wife loved the native prairie grasses, and with her I walked those railroad prairies and she taught me their names. They were beautiful.

I found my short-term job working for an aging farmer just half an hour away from my studious wife. My primary task was behind the wheel of a 1971 GMC grain truck, lurching and growling toward the John Deere combine that needed to unload. I moved forward alongside as the green snout of the combine regurgitated its belly of corn into the dump bed, trying to keep the load relatively level. I wondered if I would break traction under the burden of 320 bushels of yellow kernels in the soft, black soil.

It was the old truck’s maiden voyage for the harvest, and Fred, my new boss, and I had to jump start it to get it out of the decrepit corn crib his grandfather had built 75 years ago. It had been resting there for several months after Fred had used the derelict truck to carry a huge plastic chemical tank during the early summer to side dress the emerging corn crop with the recommended dose of pesticides and herbicides.

Fred was a very good farmer for American intents and purposes. He had some of the highest yields in the state, and crop scientists from the nearby land grant university proved this year after year with test plots on the farm. It was the yield grown from a life of hacking the culture of corn in the free university classroom of hard knocks and coffee shop wisdom.

Like his dad and grandad, Fred had gleaned crop science from wherever he could. He was the cream of the crop of corn farmers—he had reached the zenith that experience yielded at his 61 years of age, and it coincided with the time he no longer relished the long, rickety ladder climb high into the corn crib to clean the bins of corn remaining from last year before the onset of harvest.

Enter his new hire, yours truly. I would get to clean the bins

.

There were animals up there, mostly rats and mice. But there were other animals that gave me pause as I went up the loose rungs of the ladder to the upper bins. Racoons. They were the size of small bears from a diet rich in energy: corn fed coons. They had been dining on the basic ingredients of Doritos and Dr. Pepper all summer, and had turned into supercoons. Perhaps they could be called frankencoons.

Either way, they prowled just ahead of me in the labyrinth of crib chambers that connected to each other by wooden funnels and vertical passageways. I could hear them pad about, and in my vivid overactive imagination, I could foresee several of them jumping me, latching onto my neck with long talons and sharp teeth, smothering my face and my blood curdling cries as I tried to call for help—to no avail. No one would hear me in the darkened recesses of the aging crib, nor would they dare venture forth to find me.

I finally and gratefully broke daylight in the cupola peak of the crib. Here, I could look across flat-scape Midwest corn and been fields as far as the curvature of the earth would let me. The golden fields stretched to the horizon, broken only by trees around other farmsteads. I grabbed my shovel and started working. The raccoons, though considered fastidiously clean because of their ritual of washing “hands” and food before eating, were not fond of toilet facilities. They had crapped everywhere.

I scraped and swept my way downward. I decided that fecal brown lung was likely setting in. Death would probably strike me in the middle of the night. I was younger then, and prone to wild imaginings (although Caryl says not much has changed). I wrapped a bandana over my face in the shafts of light that illuminated my dim workplace. I was certain I saw raccoon eyes watching me in the low light as I performed the yearly cleanup.

The debris rattled down the chambers to the GMC bed below, strategically placed there by Fred. We had pulled the leaky spray tank out a few days earlier, and the aging corn mixed with the dust, dirt and coon crap from the crib clung to the residue in the truck bed. It now formed a matrix of dirty yellow corn/ crap/ chemical, filling up the bottom quarter of the truck bed.

Several days later, in the wee hours of our first harvest day, it didn’t even occur to us to clean it out. The matrix was mostly corn, after all. Plus, we didn’t have time. It had been raining the week before, and the ear corn moisture was finally below 20%. We could pick, and off we went.

Within 45 minutes, my green chemical truck turned grain hauler was full to the brim with corn kernels. I downshifted to get over the roadside ditch onto the county road, lurching sideways as I reached the high level of the road. As I did, a waterfall of yellow cascaded in my rearview side mirror over the side of the truck bed and splattered on the pavement. It was a common autumnal sight in corn country. The patches of sprinkled yellow marked the roads at intersections, lost over the side from a loaded truck headed for an elevator, the common collection point where corn became money.

I was headed for the local elevator. In those days, it was owned by The Farm Bureau Co-op, a collective organization of farmers that stretched from America’s sea to shining sea with the intent of buying chemicals and other soil amendments with an economy of scale and selling grain in a collective volume that allowed competition in a world market. That way, farmers could concentrate on growing crops rather than marketing them.

A farmer would most likely not know where his crop was going. The elevator was the place where trucks from the fields would dump their harvest. It was then “elevated” by auger and other contraptions to a high silo-like edifice that could gravity load entire trains with corn at very high fill rates. The trains would head off to feed mills or Great Lake ports where freighters awaited them. This particular elevator also had a small feed mill that prepared rations for hog, cattle, dairy, and chicken farms in the area.

There was a long line of trucks waiting at the elevator. They came in all shapes and sizes. Some were semis, owned by large corporate type farms; the opposite extreme was older single axle trucks like mine, usually driven by older farmers like Fred or their hired guys, who were hoping to keep their old trucks running as long as possible. The rapidly increasing price of new trucks in recent years had outpaced most farmers’ abilities to keep purchasing replacement rigs. Besides, they primarily used them during the few weeks of harvest, hardly warranting replacement if the old was good enough.

The yellow corn was connected to the green color of money by a complicated system of federal regulations, animal feed markets, and manufactured foods. Times were hard in the corn economy, but farmers had a safety net of federal crop subsidies and price supports and guarantees like crop insurance. Fred had explained to me that without them, many of these farmers would be out of business.

It was my turn to get weighed. I rolled up on the truck scale, and held my foot on the brake as the test auger dipped in my load to get a sample with its remote control robotic arm. A vacuum tube sucked a measure of corn out and deposited it in the climate controlled office. There, office assistants in street clothes checked for moisture and impurity of the crop by sample.

It was then I remembered the coon crap.

I was about to get out of the truck and apologize, or something…I didn’t really know what…when the lady nearest the window depressed a button that made the bell ring, indicating that I could move forward off the scale to the corn dump at the base of the obelisk-like elevator. I stayed in the truck and did as I was told.

I nodded at Mike as I pulled in. Fred had brought me by the week before to show me the ropes, and had introduced me to Mike. I watched him raise his hand in the mirror, signaling for me to stop. I set the brake and engaged the power take off to start the bed tilting upward. I jumped out of the truck and walked back to the rising tailgate that Mike had opened, and was beginning to spill corn through the intake grate on the concrete floor. I wondered if he was going to see the coon crap.

“How’s Glenn?”

“Good, Mike. How ’bout you?”

“Perfect. Looks like you guys are off to a good start.”

“Yep. Sure are. If the weather holds.”

“Ain’t that the deal.” Mike stepped out of the shed with me and motioned me to follow as we got away from the noise and din of the elevator and the sound of corn hissing through the auger tubes as it lifted skyward. He pulled a pack of Marlboros from his pocket, and lit up. Taking a drag, he offered the pack to me. “Want one?”

“Nope.”

He nodded backward. “Can’t smoke in there. Against regulations. Blow the deal up to kingdom come with corn dust, I guess.” He took a long draw.

“So Mike”¦where do you figure this corn goes?”

“Hog farms. We got guys with like 50,000 head within 40 miles. We bring feed out to them several times a week.”

I remembered seeing their low slung buildings a few days ago as I drove through the countryside west of town with Fred. “What do you do about protein? I mean, the corn makes them gain with all that energy, but where does the protein come from? They gotta have protein, don’t they?”

Mike took another puff. “Yep. They sure do. You know them big dairies to the west of us? You know, the ones with like 20,000 milk cows?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, we get their slaughter by-products.” Exhales. “So that’s what we feed the pigs. Ground up cows.” He blew a steam of smoke while gazing in the distance.

I mulled over the idea of pigs eating cows for a second. After being in and around agriculture for nearly all of my 28 years, nothing really surprised me anymore.

“What do the dairies do for protein, then? They buy feed from you, too, don’t they?”

“Yep.”

Mike dropped his cigarette on the concrete, and carefully ground it out with his boot, and turned to look at me as he walked away into the din and smiled. “Ground up pigs!” he shouted, as he disappeared into the dust of the elevator and closed my truck gate.

As I listened to the corn rattle up the elevator, I realized that there was a total disconnect, even for me. The golden kernels weren’t food. They were a commodity. That could mean that they were the basis for high fructose corn syrup in Dr. Pepper, or the material foundation for a feedlot ration for pigs and cows. The closest food thing I could think of was that it might make it into a cardboard container of Quaker Corn Meal. It’s the brand with that smiling 17th century stereotypical Quaker gentleman on the front.

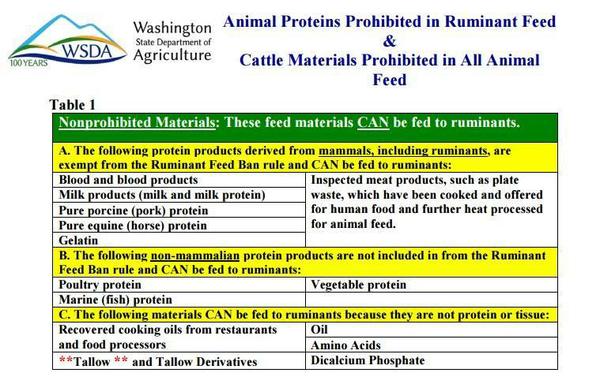

Mr. Quaker is smiling. And it’s all smiles as they advise us in the Code of Federal Regulations (21 CFR 589.2001) that it is still OK in this day and age of 2016 to feed pig, horse, fish and chicken meat, and even rendered cow fat to milk cows or beef cows. Even grass fed. USDA’s now defunct Grass Fed Regulations allowed for ground up fish to be fed to cattle to be labeled as “grass fed beef.”

I think it is hubris- the human trait of excessive self-confidence that we believe we are right because we are smart. It’s smart to use up what is otherwise waste (carcasses), and repurpose them in an economically efficient way”¦or at least everyone thought it was smart to feed ground up cows to living cows until BSE (mad cow disease) came along. Then it didn’t look so smart. Apparently we’ll need something else to manifest before we realize maybe it’s not so smart to feed ground up pigs, horses, fish and chicken waste to cows.

Cattle are elegantly designed to eat grass. They can turn land that cannot grow fruits and vegetables into productive land that grows nutrient dense beef protein that is healthy for people to eat. And those seas of grains that were once seas of beautiful prairie grasses? They conservatively produced 50 million buffalo just in the prairie states. Today there are about 85 million cattle in the entire United States. Nearly 70% of the grain grown in the U.S. is fed to cattle and other animals in feedlots. Can you imagine how different our agriculture and landscapes would be if instead of growing grain and hauling it to animals in feedlots we grew grass and let animals graze it?

Cattle need energy, protein, and dry matter. Good pasture and healthy native rangeland provide it all. By partnering with nature, we can provide cattle what they need for their nutritional well-being, while improving soils, capturing carbon, improving wildlife habitat, and increasing biodiversity. And we can grow amazing beef for people.

The beeves came up to the house today. They have the entire west pasture now, and they fill on green and fall curing grass on a diverse sward on some 250 acres. They came not looking for more grass, but to say hello, I think. They looked shiny and full as the setting sun silhouetted their black frames while they continue to graze, picking their own “ration” out. My only job is to ensure a full diversity of choice (no monoculture pastures), so they can balance their own needs for wellness. That aspect of choice makes our beef some of the best I’ve eaten, I think. I’ve hunted and harvested all kinds of game in these mountains from elk and deer to ducks and grouse, but our beef beats them all.

I’m thankful for it. Like Fred, we’ve hacked our way to creating growing practices that result in this wild goodness, but where he went forward in modern science and practice, it took us going backwards to the very roots of what our beeve’s ancestors ate and how they did it. Amazingly, much of those ancient rhythms were hard to rediscover; we are losing ancient instincts and knowledge even in our bovine’s genetic material. But we’ll continue to find our way, thanks to you, our partners.

And that’s the deal; the bottom line. Without your faithful attention to partnering with us to serve up wellness that we create through husbandry, we could we no longer be sojourners on this path to rediscover wild protein. We’re hoping we can be a small part of transforming agriculture into one that honors cattle as herbivores and converts carbon-releasing acres of grain into carbon-sequestering acres of grass.

Thanks for being part of this work we do; we are so very grateful to each and every one of you whether you purchase a whole beef from us or 3 pounds of burger.

Happy Trails!

Glenn, Caryl and girls.

Julene Jacobsen

Thank you so much for farming the way nature intended. I love your beef so much and hope to be blessed to have it for a long time forward. I am a true beleiver that “you are what you eat.” I walk down the isles of the grocery store and am saddened by the processed food that is marketed to children (if it can even be called food). My motto for a good diet is to eat food that is as close to nature as possible, in season and as close to where I live as possible. Thank you for letting us get to know you and your family. You are a great blessing to me and my family.