“There’s gold, and it’s haunting and haunting;

It’s luring me on as of old;

Yet it isn’t the gold that I’m wanting

So much as just finding the gold.”

–Robert Service, from ‘The Spell of the Yukon.”

“Hey Marc. Chris. Check this out.” I gestured into the murk of a thick subalpine fir and Engelmann spruce patch from the more open forest of lodgepole we were hiking through. “I’m wondering if this is it.”

It was 1989, and we were high in the seemingly endless pitch and roll of dark-timbered subalpine forests, high up on the Continental Divide boundary between Idaho and Montana when I spotted the log shack nestled in the thick spruce timber by the spring.

The spring bubbled clear and steadily from beneath a tiny copse of willows, and I knelt down to drink as I eyed the cabin. Two of my forestry companions, Marc and Chris, walked over to inspect the exterior of the little building. Now that we were close, we saw a few other little shacks illuminated by the moats of sunlight streaming down through the thick canopy.

It was a tiny sort of village, and we felt as if we’d just stepped a hundred years back in time. The graying and cracked plank door of the largest log building was propped open a tad, and I walked over and pushed my way in.

We were on a forest inventory reconnaissance of this part of the Federal forest reserve. The three of us had our measuring gear comprised of compass, clinometers and tree diameter tapes loaded up in our ‘cruiser vests.’ We were working off paper USGS topographic maps to quantify the type and quantity of timber up in these parts. We had absolutely nothing on paper about what was here; at this time in the late 80s, there wasn’t even a Continental Divide trail created yet, let alone GIS or GPS. This particular blank spot on the map was only accessible from Montana, and we had taken a big circle route on our dirt bikes on old logging roads just to get close enough here to hike in. There were no roads in this area; only faded and downfall-clogged trails, now overgrown and a century ago grubbed out by men, oxen and teams of horses in some of the most rugged country in the lower 48.

And every now and again, we would come across a settlement just like this. Under the thick forest cover that spanned hundreds of square miles, you couldn’t see these habitations from the air. So it was highly unlikely anyone else had been here, except if by foot, like we were now.

The door creaked loudly as I pushed it open, and dragged across a massive pile of spruce cone casings that a mountain red squirrel had packed into the cabin. As the three of us pushed in, our eyes first had to adjust to the gloom inside. Two tiny windows, with glass intact let an ethereal green spruce forest understory light into the dim room.

It was only one room, and a plank table and benches made up the center. A woodstove that doubled as a cooking surface sat in one corner, and a low series of shelves sat on another. Rusted cans and a few forks and knives sat along those shelves; a pack-rat had made a nest on one shelf, full of random human debris such as can lids and tobacco tins.

It was a rough little room, and had little creature comforts, except for the critters that now lived here. As far as the human occupants, we decided that they must have lived here for several years, and we knew from the ceiling height that they must have been shorter than the average human today.

Good thing it was that they were less in stature, because of what they had come here for. They weren’t simply trapping, or hunting, except for subsistence. Actually, I suppose they were hunting for the elusive “lode.”

The lode was none other but gold. The shiny mineral has bewitched men since the beginning of humanity. The search for it had taken them to the farthest reaches of the earth—in some of the remotest mountain country. Why mountains? It was because in them was parent material. In in the vast ranges of rocky crags were bands of quartz in granitics that just might yield the yellow.

The gold was the ‘why’ of their coming. From where is another question. The fact is that originally, they came from everywhere. Gold fever reached far and wide across the globe, infecting men from Europe, China, and as well as America’s East Coast. Most of the miners in the heights of Idaho migrated first from California’s gold fields that played out during the 1850s.

And so, a stream of miners coursed through the high country with powder, pick and shovel. There, they found streams of white quartz-intruded dikes in otherwise solid block formations of granite. And they followed them across landforms as the rocks reared up through the forest duff and trees and formed cliffs or bony ridges devoid of timber. And when quartz looked promising, they occasionally found gold, especially when they took dynamite and their hand tools and dug shafts and drifts deep into the very bowels and bones of the Rocky Mountains.

They were the hard rockers. They were going for virgin ore that had never been found by river or glacier. The yellow they searched for was still bound and determined to stay in the matrix of skeletal planet, and would yield only to the blast of explosives and pick. It was a clear cultural distinction from the placer players. The placer miners worked with and in the ways of water, using the principals of fluvial movement and gravity to feather the heaviest mineral-gold from the grit of watercourses.

Shorter men obviously fared better underground than the long and lanky. And so, with blast of powder and pull of pick and slide of shovel, they made their way in. They built shelters—cabins well chinked and well warmed with wood. They packed flour and gear in on mule and horseback. Their underground labyrinths they burrowed into the mass of mountains became their daytime home–or their forever if the commonality of cave-ins occurred and claimed them.

Their night-time home was the cabin they created. It was a safe and sound respite from the treacherous shaft.

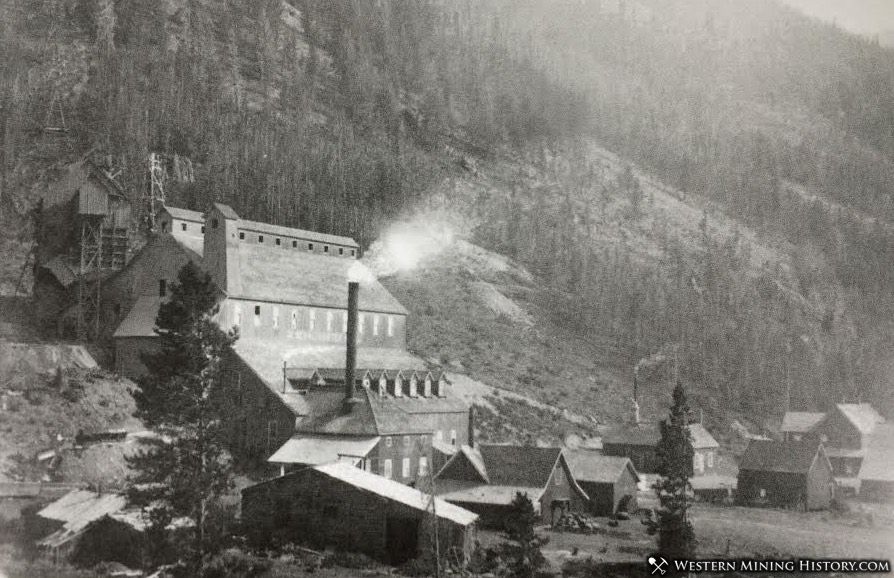

All of our mountain country is littered with the leavings of miners. A hole here, a shaft there. A shack, a shanty. A tumbling rock mill, or a fallen down stamp mill. In Idaho, we live on a richness of rocks. That same deteriorated parent material we grow Alderspring grass on stands still intact on the mountains we live and work in. Untold deposits of precious ores still stand secretly tied up—perhaps forever?—under the hooves of our horses and bovines.

Back to 1989: I turned to Marc and Chris. “Well, I guess we’ll keep our eyes open,” I said. The crew knew what I meant. Back to plots, tree measurements and stems per acre. But while on these forest recon missions, we had in the back of our minds a sort of holy grail of old mining cabins.

It all started in a conversation I had in the pickup one day with my former boss, Bill Steiner. Before he left to take a job in Montana, as we were heading up the Lemhi Valley, he swept his hand up toward the high divide.

“So way up in the head of Wimpy Creek or Pratt—I can’t remember—up there along the divide, I found an old mining cabin. I’m hoping you’ll bump into it sometime. I’ve always meant to go back, but never got it done.

“I was on a compass navigated inventory line, and there weren’t any landmarks; the whole country was pretty much solid burn-regenerated lodgepole pine timber as far as you could see. So I know I’d probably have a hard time finding it again, but it sure intrigued me.

“Anyway, I went in the cabin. And I’ll never forget it.” Bill glanced over at me in the passenger seat. I was all ears. “You see, it was all there. It was as if the guys or whoever they were had just stepped out, and I stepped in, like stepping back in time. The table was set, like they were getting ready to eat. There were canned goods in the cupboard, and cut kindling wood at the cookstove. I mean—it was a little creepy. All the personal belongings were still in there. I mean, it was dusty and all. Like it had been sitting a hundred years or so, waiting for me to find it. Mining gear, clothes, lanterns. Everything.”

Bill had found a time capsule. A perfect view back in time to the manner of miner.

“That is weird,” I said. “Like maybe he’s buried in his shaft or maybe a griz got him or something.” We both knew it was possible, because in that day and age a hundred years ago, grizzlies were pretty common here. And they liked prowling around human habitations to glean from their ubiquitous piles of kitchen scraps and tin cans. The poor gent may have become lunch on the way to latrine–or buried in the common cave-in. Never made it to dinner. Ouch.

And so, when on recon, we kept an eye open for the old boy’s cabin. And had yet to find it.

And now, 35 years later, in 2022, I know that somewhere, it’s still up there. In fact, just today I glanced up there to that unbroken stretch of timber from our beef packing shop in Carmen, Idaho, and I often wonder about continuing the search through that unending dark divide forest.

How many of us get a chance to step back in time—through a graying, wood-plank portal to a gold miner’s life 130 years ago?

I, for one, would enjoy it, even if I would never find their ‘lode.’ Like Robert Service’s miner, the quest isn’t in the gold or the goods. It’s in the finding.

Happy Trails.

Deb Olsen

Oh how I’d like to step back in time to go through those old cabins with you, I have always been intrigued by seeing how others lived if only for the brief time they were there. Have you ever found anything interesting like a picture or trinket of some kind? I’m sure since they were mining for gold it wasn’t a set up home like that but more of a shelter from the cold type set up. I always love your stories they’re the best!!

Natalie

Over the years I’ve found bits of pottery, glass bottles, and even some art when planting and weeding my property, and wondered how the items came to be.

Years ago I read a fascinating book, The World Without Us by Alan Weisman, about what would happen if humans suddenly disappeared; how things would cease working or fall apart, and the impact of our built environment on the planet.

Not that everything is destructive of course, but still much better to do as you have done, respecting and improving your part of our home planet.