I still haven’t got enough of the air. I’ll catch myself taking in deep draughts of it, filling my lungs to capacity, and slowly, reluctantly, guardedly, releasing. With it comes the fragrances of fall pasture; of legume flowers on the big meadows at home; red clover and sainfoin. I tell myself I’ll never take the clear mountain air for granted again, but I know I will. But for now, I walk in gratitude; the smoke is finally gone.

As is the summer. It’s hard to believe that summer is over. Yes, we do have some warm days still in front of us, but last week brought snow to the high country and wetting rains to ours. It pretty much squelched the remarkable power out of the Rabbit’s Foot Fire, the 35,000 acre wildfire that was chasing our tails over our high grazing country.

It also froze this week. It was a light one, but some of those zucchinis in our home garden show a little black on their outer leaves despite five sprinklers putting warm water over our kitchen crop. I discovered the damages one morning collecting my breakfast greens under a backdrop of crystal clear peaks frosted with new snow under azure skies. It’s OK, though. There is enough of the green summer squash accumulating in our kitchen that sometimes I trip over it. Some are the size of bowling pins. The kids say we’ll make chocolate cake out of them. Although I’ve seen such zucchini hocus-pocus occur (the cake was wonderful), you’re still not going to see me cry over the frosty demise of green squash.

I noted on Custer Classifieds, our local Facebook clearinghouse for everything from prom dresses and pistols to kitsch and cars that one poor gardening soul thought that she could charge a dollar each for her zucchini. Instead, I think she needs to tape a dollar to each one—then, maybe, just maybe, she’ll get them moved. She’d be better off doing a hit and run at the library, engaging in the worst of garden debauchery that occurs commonly this time of year in our small mountain towns: dump shopping bags full of the zucchini bounty in the front seats of unlocked cars of your neighbors and friends.

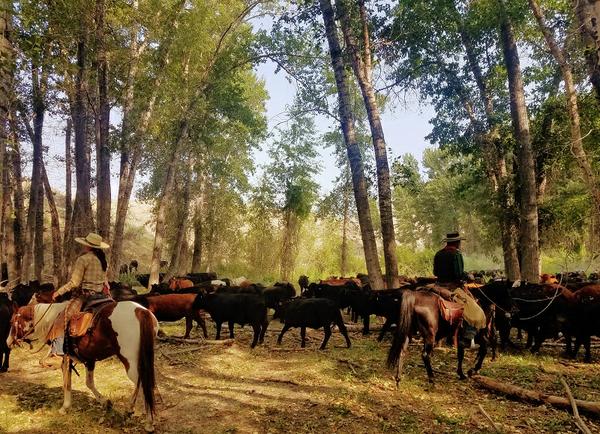

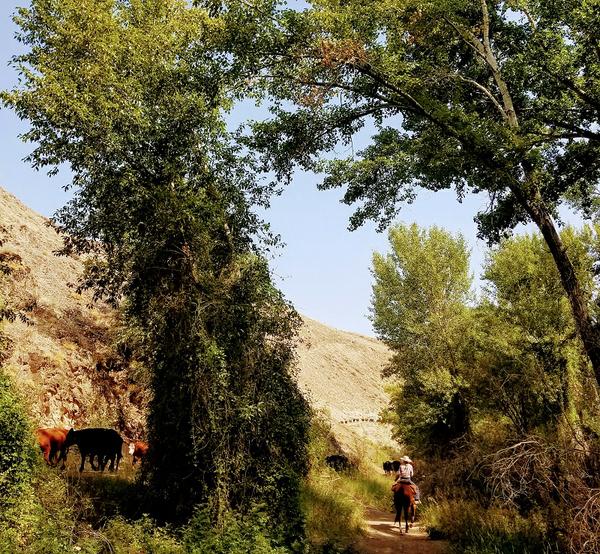

It’s also the time that everything changes on Alderspring. We trail the cattle down from the summer grazing range, a 3-day task covering nearly 10 miles a day. We pull camps and conduct end of season monitoring. The latter captures photographs to document the ecological changes that the wild country undergoes under our management. This year, the crew took over 1000 repeatable photographs that are relocatable because we GPS’d each location precisely.

So, after nearly 600 grazing trail miles, 8 remote cow camps, and getting run off by a wildfire that burned 8000 acres of our grass, the cattle and crew have returned to the home ranch. The beeves are inhaling deep draughts on their own—rich fall pasture, verdant and flavorful with grasses, clover, and wildflowers. They have about 500 acres to wade through here. Much of it we cut earlier for our winter hay stack and the late summer regrowth is lush and tender. It will last them until the snows of winter appear and sweep green beneath the carpet of white.

We’ve left our grazing country in great condition. All of Alderspring’s cattle that left the ranch in springtime are back home again, except of course the ones we actually harvested off of the high range. And the wild range landscape itself has never looked better. We camped adjacent to several creeks, and despite our close proximity to those critical wildlife and fish habitats, we left them unmarked by a cow’s footprint. Of the 55 miles of live water on our grazing range, we impacted less than 1000 total lineal feet with our cattle (that’s 0.3 percent of total stream distance). We either crossed creeks in these areas or got our steers a drink there.

What that means is that our wet areas, the areas that normally have the greatest impacts from cattle grazing and trampling, are in full regeneration mode. We are seeing species (both plants and animals) express themselves that we didn’t even know we had. And what that means is there is more food and cover for the animals that live there.

Crew boss Anthony counted more than 30 individual sage grouse on one of his journeys up Little Hat Creek. Sage grouse are on a precipitous decline throughout the West and are petitioned for listing via the Endangered Species Act, and no one really has the answer as to why. But on our range, after 4 years of carefully herding our beeves away from critical habitat areas, they are booming.

I think it’s because nearly all the wild range landscapes in the West have been subjected to nearly uncontrolled grazing for over 120 years (we are the only ranchers we know that are herding our cattle and completely planning and controlling their grazing choices). Uncontrolled grazing has taken its toll: my theory is that there are plant and animal species that have been extirpated (or made extinct, locally) from these wild lands. Animals like sage grouse and bull trout cannot thrive without these missing habitat components.

Keeping Alderspring cattle completely out of creeks and wet areas is life changing for the ecological condition of those habitats and the animals that use it. At the same time, we can realize better weight gains for our cattle and more plant diversity in our beeves’ diet by carefully choosing which mountainside to shepherd them up to each day. Swiss and French alpine herders call it livestock meal planning. They have classes and books on the subject. And we learn from them. This idea is novel today, but the work is ancient and traditional.

As you can tell, I get excited about the regenerative approach that we’ve learned about grazing these native landscapes. Not only are those wild ecosystems dramatically improving under our change in management, but our cattle are healthier than ever. Once again, not one of our cattle was sick up on the range, and none needed doctoring. It’s nutrient density 101; the soils are organically fertile and biologically active. It’s because these lands have never been exposed to the plow or pesticide. The only steer doing a bit poorly is one we call Snakebite. He was bitten in the face by a rattlesnake in late June, but he is safely home and seems to be recovering quite well on the deep green.

But there is another aspect to what we do that may be the most important of all. Sure, we’re in the business of regeneration-in the wild protein with its health benefits that we raise, and in the restoration of wilderness landscapes on a large scale. But I was impressed with the importance of the third leg of a three-legged regenerative chair this summer as I was working with the crew.

It has to do with creating continuity in these new regenerative ideas we are moving forward on. I am 56 years old, and although I still have a lot of life in me (I think), I can tell that the machinery of body is not what it used to be. My bony butt gets a little saddle worn after a long day (those padded seats are looking better all the time), my bed roll likes to have more padding, and when I roll on my dirt bike and road rash my body, it takes a little longer to get up than before.

But my team is just getting started. They are young. I had a dozen people working for us this summer, all in their 20s. Even though I would recommend that they don’t thrash their bodies like I often have with horse and bike wrecks on the ranges, they soak up not only the what and how of what we do, but also the why. And even though many of them are gone with the end of summer, now back in the hallowed halls of education, I am positive that they will carry the lessons they learned living in the backcountry on horseback with Alderspring beeves for the summer. It will affect how they think, and how they relate with others. I know, from experience, that they will see the world differently, and how important it is to maintain the integrity of our natural world.

And that, I believe, is one of the most important things we do. Because when Caryl and I become old and in the way, there will be others who pick up the baton to practice stewardship of these landscapes for years to come. And they will do it better than we did. We talk of restoration ecology and using our beeves as the tool to get it done and get hung up on thinking it is just about what we do in the here and now on the land. But the only long reaching attribute of what we do is passing that regenerative vision to the next generation.

And you, my friends, are partners in that enterprise. When you trust us to provide for your table, you also entrust us to convey vision to those Millennials and Zers. You are paying it forward. Despite what we hear about those dreaded Nexgens, I for one, have great faith that they will carry that ideal on, and even do it better than we.

Happy trails,

Glenn, Caryl, Cowboys & Cowgirls at Alderspring Ranch

Leave a Reply