Virgil Williams cradled the side by side 10 gauge in his right hand, reins in his left. Although his bay horse shifted weight under him, the barrels of the scatter gun stayed trained on the chest of the Custer County Sheriff, 20 feet away. “Well, Sheriff, what’s it gonna be?”

“Put the gun down, Virgil.” The Sheriff eyed Virgil’s index finger of his right hand, resting on the trigger. He knew too well how both barrels could fire at the same time, and would pack enough wallop to unseat him off his horse, leaving him a pockmarked carcass the ravens would quickly flock to in the heat of high summer. Even if Virgil didn’t use both barrels, the blast of buckshot would likely kill the lawman. Fact is the gun-toter would probably save the other barrel for the deputy.

The sheriff eyed his partner. He didn’t think the deputy could draw fast enough to keep up with Virgil’s finger. But then again, a ten-gauge recoil packed some serious wallop, especially one handed, and it was likely that Virgil wouldn’t even be able to quickly deliver another well-aimed squeeze on the trigger. His horse was edgy too, probably wouldn’t put up with the blast. The Sheriff weighed his options.”‹”‹”‹”‹”‹”‹”‹

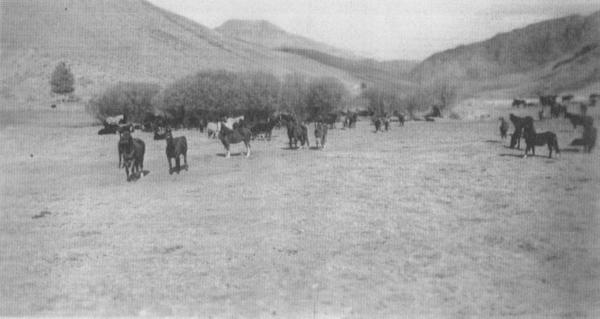

“What’s it gonna be, Sheriff? It’s like I said. You’re welcome to come through my gate and try to check my brands. You just ain’t gonna be able to ride out.” There was a trace of a cynical grin as he turned his head slightly, and spit some tobacco juice in the dirt. It made a little wispy cloud of dust where it met the ground. Virgil swung the gun toward the deputy. “He ain’t a gonna be able to ride out either. You boys just head on back to where you come from. You got no business here.” He threw a nod behind him to the red and white shorthorn cattle that dotted the low hills around the ranch. “All of ’em got my iron on ’em, Sheriff, and only mine. You can check brands this fall when I trail ’em down to the railhead.”

The Sheriff sat quietly, thinking. He had been hearing reports of Virgil’s wayward branding iron, enough of them that he thought he’d better have a look. The other ranchers who ran cattle in this remote piece of Idaho were getting wise to the game after coming up short on calves the last few fall gathers.

The Sheriff knew what Virgil was likely doing; he was picking calves that never saw a branding iron because they were born on the range, and riders in the Morgan Creek Association either missed them in range brandings or figured they’d brand the calves when they had them gathered somewhere on some rare flat and more convenient piece of ground where they could start a fire and put their mark on them.

The Sheriff squinted as he looked toward the sunlight and eyed the cattle on the low hills beyond Virgil. If only he could get a look at just a few; they would stick out readily to his trained eye. The calves would have Virgil’s mark on them; the mothers, Morgan Creek’s. Then, he could return with a posse to engage Virgil. But without proof, it would be a long ride with a lot of men if the evidence didn’t exist.

Just by Virgil’s lack of willingness to let him ride through them pointed to his guilt. The sheriff played out the chain of events in his mind: later this fall, Virgil would wean the calf off, and turn the mother cow back out on the range before the Morgan Creek riders combed the hills for the fall gather. “This one’s missing a calf,” they’d say. “Must have got eaten by griz or wolves.” Those things happened.

But the high number of missing calves the past few falls was pretty strong evidence that someone was rustling calves. And Virgil Williams was the one and only prime suspect on his Little Hat Ranch, which lay smack dab in the middle of all the grass country peppered with 5000 head of Morgan Creek’s largely unsupervised beef cattle.

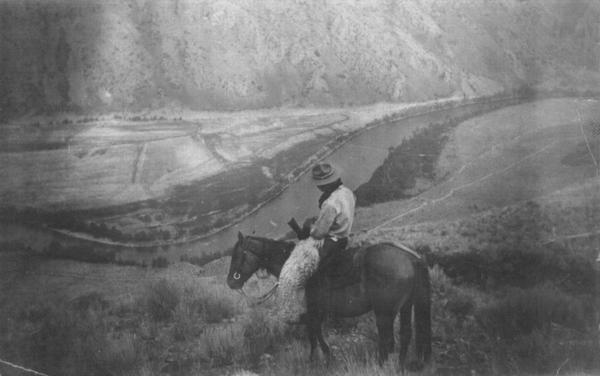

It’s probably why Virgil staked claim on the remote place. To him, it was a land of opportunity, and the low hanging fruit of abundant and nearly wild and wandering cattle beckoned to him. He rode into the valley horseback, somewhere around 1910, found his piece of paradise, and staked claim on the little creek surrounded by rugged hills. He built fence, a log cabin, and dug irrigation ditches to spread water out. He filed on the water rights in 1920, and filed for a homestead in 1932. Virgil lived and thrived up in the tiny Little Hat Creek valley as the First World War ravaged Europe, and even as the Great Depression ravaged America. And he didn’t even need to bring many cattle to support his grubstake. He simply found those who had “lost” their way from the main herd, and gave them a home where they would become fat under his wary eye.

The additional monetary benefit was that he wouldn’t have to winter the mother cow. Virgil happily returned the “borrowed” mama to the range to rejoin the other 5000 or so Morgan Creek Association cattle, just before the fall gather and the “benevolent” ranchers would be none the wiser. Virgil, meanwhile, could pocket the greenback yield from “his” steer at the Mackay, Idaho railhead while the victim rancher could open the hay pile for its mama for another long winter. In his mind’s eye, the sheriff could see Virgil Williams smiling contentedly at the fire in his snug cabin in Little Hat counting his greenbacks. Meanwhile his ranching neighbors and unwilling partners were out in the bitter cold forking hay to hungry cows gestating the next year’s calf crop.

It wasn’t if they uncovered Virgil’s plot; it was when. Angry neighbors would hang him as soon as they had some semblance of circumstantial evidence (or maybe they wouldn’t wait that long). The Sheriff’s eyes wandered up to some pine trees up on the hill above the lower end of the valley. “They’ll do, he thought. Not if, but when.” Sometimes the long arm of the law would get a little help from cowboy justice fueled by the fire of anger. It was 1917, after all, and the sheriff had a hard time keeping up on horseback in a county that was roughly the size of Connecticut.

His job was to keep the peace, but he didn’t have a lot of choices with that shotgun pointed at him. “You win, Virgil. We’ll turn around.”

Virgil Williams said nothing. He turned ever so slightly, and spit out another squirt of green effluent. The shotgun remained poised on the Sheriff’s midsection, finger on trigger.

Sheriff and deputy backed their horses up for the first few paces, keeping eyes fixed on the rustler. Then, they turned their mounts, looking over their shoulders, and trotted back up Pig Creek Canyon from whence they came. Just before the canyon turned, sheriff and deputy stopped for one last look. As the dust settled, they could still make out Virgil Williams. He held his ground, shotgun at the ready. They touched heels to their mounts, rounded the rock outcrop and lost sight of him.

It’s springtime, now a full 100 years later on Little Hat ranch. The meadows that Virgil cleared for his illicit cattle operation are still there, abloom with wildflowers. Little Hat Creek bubbles through thick stands of willows and birch that had been cleared and burned to make more meadow for grass-hungry calves. The cabin is gone, but the weather beaten and cracked outhouse still stands. It’s a two-holer. I guess Virgil had occasional guests.

As you probably figured out, Little Hat Ranch is part of Alderspring, as are all the ranges for many miles around it where Virgil ran his rustling enterprise. When you visit the Ranch, 10 miles after leaving pavement on rough two tracks, you can see why it is where many cattle ended up. It was fish in a barrel for Virgil. Five canyons drain into the ranch. It was like an interstate highway exchange for cattle, and visionary that he was, Virgil Williams was likely smug in his newfound success.

But sleepless nights and uneasy trigger fingers can take their toll on one’s self condemning psyche, especially when combined with the unavoidable progression of age. Virgil managed to escape both noose and the law for over a decade until one of the ranchers he stole from, Mike Ellis, apparently confronted him. Somehow Mr. Ellis ended up with the entire 760 acre Little Hat outfit with no money changing hands. Virgil quietly disappeared, his plea bargain apparently accepted, never to return to the Hat Creek Country. We’ll never know just what the deal was, but I’m guessing Mike Ellis mentioned to Virgil that certain people, if told the truth about his crooked cattle encounters, would likely take matters into their own hands.

We are equally captivated on the Little Hat country as well, albeit for some quite different reasons than Virgil. But some are the same. Like him, we know that despite its rough and tumble features of canyon and creek, the Hat Creek ranges have hard grass that puts fat on beeves like no other. The bonus Virgil didn’t pick up on was that these diverse native ranges produce exceptional flavor in beef, different but reminiscent of the depth and complexity of flavor and nutritional density of the wild game animals that we share the country with. Unlike Virgil, we have created an honest living off that landscape, thanks to your partnership.

And because of that there is no one out there seeking to fit me with a new necktie. It does make for better sleeping. I never liked ties much anyway, although I do have a preference for loose-fitting silk bandanas. We’ll just keep the neckties to that kind. Happy Trails.

Leave a Reply