Dear Friends:

I’m writing this before sunup, and the light is just coming over the ranch. It’s still gray, before the sun bathes the highest peaks with the rosy orange of alpenglow. I can see across the valley to the Hat Creek ranges that vault up from the Salmon River nearly 5000 feet to the 10,000 foot Taylor Mountain ridge. The signature of the end of summer is clearly marked at the massifs highest peaks–they are blanketed with new snow of a few days ago.

The air was invigorating when I was outside earlier this morning, filling the lungs with a draught filled with the fragrance of coming fall. The nicest thing is that it’s clean. Forest fires have been ripping through the forests a couple of hours south of us, and have left us smoked in on some mornings. But the rains washed it all away, and the crystal clarity of our mountain air was back as of yesterday. I’m sorry I ever took it for granted.

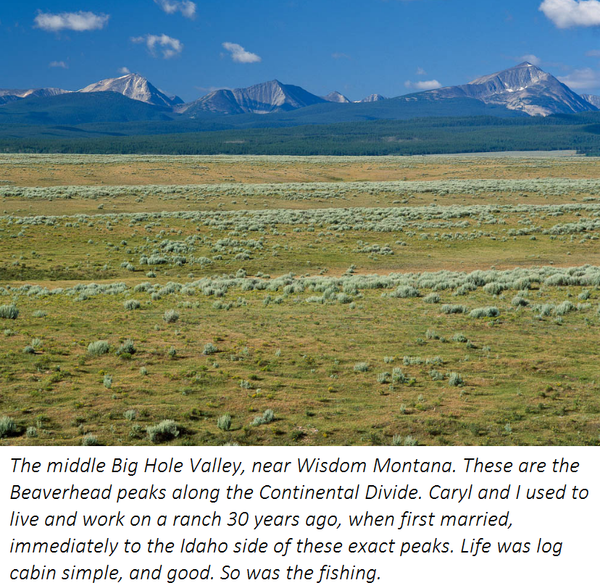

The air was crystal clear in the Big Hole yesterday. It’s one of the remotest mountain valleys in Montana. I was passing through with my long stock trailer after bringing beeves up to the processor. I usually don’t go through the Big Hole, instead venturing over Bannack Pass to cross the Continental Divide into Montana. But Highway 29 over Bannack isn’t paved, and the dirt has gotten very rough over the summer. Just last week, Melanie’s car almost self-destructed while driving the washboard travelway. Her driveline actually rattled loose on the rockiest state highway in Montana. It could have wrecked her car, but she wisely called yours truly at 11 PM that night. I was able to cobble it back together by crawling under it with wrench and bar. I was reminded that Subarus are not designed for 6 foot six operators–or even skinny mechanics underneath. I almost got stuck under her car trying to get at the problem.

Anyway, it’s why I didn’t haul our beeves over the rock-strewn track. I took the paved way over the Great Divide, still over 7000 feet, and longer, but smooth as silk as my 40 foot long truck and trailer snaked its way around curve after curve. The Big Hole Valley delivered the goods of beauty, and made the longer drive well worth it. The valley floor, perched at about 6500 feet, was still fairly green in spite of the dry and warm summer we’ve had. It’s a broad valley, in places 15 miles wide. An on either side was an unbroken wall of snow dusted peaks.

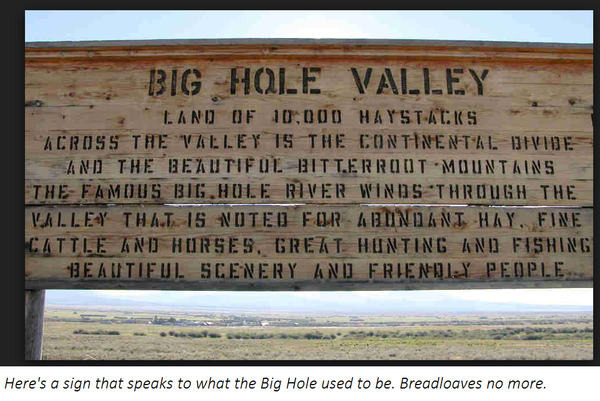

It’s been a couple years since I’ve passed through the Big Hole. The first thing I noticed was the complete lack of haystacks. What I mean is that there were plenty of round bale haystacks, but there used to be huge breadloaf haystacks that pretty much defined the valley. In fact, visitors to this stretch of hidden Big Sky used to call it the valley of ten thousand haystacks, referring to the huge piles of loose hay that the locals placed throughout their native grass hay meadows for winter feed. They used 100s of draft horse teams that raked and stacked the hay with “beaverslide” stackers–hand built huge contraptions that stood some 60 feet in height, made of the abundant lodgepole pine that the locals harvested from their forest cloaked foothills that ring the valley. These frameworks ingeniously dropped the hay down to form the tall breadloaf stacks.

Years ago, Caryl and I used to work for an old gentleman in Idaho who put his hay in stacks the same way. One of us would be up on the tall stack, some 15 feet off the ground, pitchfork in hand. We were the stacker, and it was our job to level out the hay and make it lattice together into a tight mound. The team of Belgian draft horses below would tilt their ears upward toward the stacker. One quiet command and the would lean forward into the traces, pulling a wire rope that through a system of pulleys, lifting a big pile of hay upward along the tilted lattice that formed the “beaverslide,” and shooting it up onto the top of the stack (often covering the stacker). By the tone of your voice, you could control the forward motion of the team, and adjust just how far the several hundred pound wad of meadow hay went on your stack–those horses paid attention. Then with a word “back,” they slowly backed up, grabbing a bite of rich pasture grass along the way, and recocked for the next wad of hay to be reloaded at the base.

Meanwhile, the hay crew compadres scattered across the fields with teams of their own, quietly driving rakes that pile and pushed hay toward the beaverslide. It was pretty idyllic, and even fun. You worked together with a great crew, ate wonderful ranch cooked meals together (and Beva, our cook, would be very generous with cream and butterfat from their cow), and worked until the long days finally went dark.

As I drove through the Big Hole, I passed many beaverslides, parked and unused. They were relics from a bygone age, and had been replaced by the iron horse. I saw no draft horses in a valley where they were once common, it seemed, as cattle. In a short 20 years, all was changed, and the way of haymaking that defined the Big Hole was history.

The breadloaves were largely replaced by round bales of hay, weighing about 1500 lbs each. If you enjoy spending hard earned monies on rustable iron, they are the paragon of efficiency and ease, both in making hay and handling it. Even feeding such bales is much easier, barring any breakdowns. I watch my neighbor feed round bales with his pickup truck that has a special attachment that allows him to pick up two bales (nearly 2 tons of hay) and unroll them across the feed ground. Often, he’s in there with the radio on and in a t-shirt, heater blowing warm air that fills the cab on any given zero degree day.

In contrast, I’ve fed off the breadloaves with a team and sled in drifting blizzards where exposed skin would freeze in minutes. It seems like a no brainer to mechanize to round bales, especially in the Big Hole, where temps can drop to 40 below zero, even on a nice sunny day. On some of those blizzardy days, it was actually dangerous to be out there.

With such efficiencies as mechanization and speed comes a necessary economy of scale to pay for such things as big green tractors and new pickups equipped with the latest bale handling equipment. So as an operator, the incentive is irresistible to increase in size with more cattle and more land, maybe absorbing the place next to you as those aging Mr. and Mrs. Smiths retire. And your neighbor does the same–growing to pay for equipment even while their net paycheck per pound decreases as everything else increases. Maybe your wife takes that town job as you increase in size and scale. Perhaps your cash flow crunch causes you to sell to that investment banker from Boston. You stay on the land, with your cows, and the equity underneath your feet is no longer yours to pass to your children.

It was happening in the Big Hole. Even as I drove through, I noted abandoned looking farmsteads with hay meadows freshly cut around them–part of the absorption of real estate with bigger land ownership to be economically viable.

But it all comes to a high cost to the land and to the cow, and it’s because we gravitate from husbandry of land and beast, which by definition requires relationship, and a fairly intimate one at that. The modern rancher practices his trade more often from the seat of a tractor or pickup, rather than from the back of a horse. Windshield view of land isn’t quite as intimate as under foot, either your own or your horse’s. Hayfields get larger as equipment gets faster, losing the brushy fence rows that provide habitat and shelter for wild things. Monoculturing is encouraged for harvest efficiency and timing. To the occasional visitor, these valleys like our own Pahsimeroi and the Big Hole are unchanged; unsubdivided open space still abounds, and cows still dot the landscape. But to those of us that live here, the change is enormous. We witness change and loss of ownership after generations held it intact, often meaning larger and larger operations, often owned by interests from outside the valley. It is, as Wendell Berry called it, the unsettling of America.

It’s also the loss of husbandry. A difference: When running the mowing machine behind the team of horses, we would stop when spotting a dappled fawn in the diverse native grasses before us, waiting in silence and wonder as it trotted off. Or maybe it’s a long-billed-curlew nest. Now, rotary 13000 rpm disc swathers moving on laser-planed alfalfa monoculture pool-table level fields at speeds of 15-20 mph mow them both down without missing an alfalfa beat. Sirius satellite radio in air conditioned cab hermetically seals t-shirted operator on cell phone from the bloody debauchery outside.

The loss of husbandry. It’s not just what we see, but includes what lives in symphony under our feet–the living soil matrix that founds all of life that teems on it, from the grass, to the bovine, to the bird that roosts in the cottonwoods along its edge.

**********************************

A hunter called me early this morning wanting to kill a pronghorn antelope on our sagebrush ground across the river. If you haven’t spent time around antelope, they are the graceful multicolored plains gazelle relative that is a no holds barred speed record holder in the world–excepting the cheetah. I once raced one on a smooth dirt road in the next valley in my pickup. A herd ran effortlessly alongside me, about 50 feet away, holding steady at 55 mph. I accelerated evenly, and purposefully to pull ahead. As I reached 60 mph, a lone male broke away from the band to within 10 feet of me, and, accelerating, cut me off as I held at 60. He had the last word in speed, and my respect forever. Eat his dust, short sprinting cheetah.

Hunter man: “There are tons of them over there. I’m seeing them there every day. Would you mind if I just killed one of them?”

“Actually, I would. You see, that is the only sagebrush place where they can’t get shot at–that I know of anywhere in the valley. It is public land all around us; can’t you find one out there?”

“They look like they all come to your place.”

“Well…they do. They have their kids there, and see our place as a spot where they can be safe. I think they need that.” Deep breathing and no words on the phone. “You know, if you want to hunt elk or deer, let me know. I currently have two hunters down there in the river bottom trying to get an elk, but when they are done, I’d be happy to let you try to get one.”

In fact, the elk and deer are a little out of control. They have large amounts of private land in the dark cover of the river bottoms that serve as refuge for them, as many landowners do not let people hunt. As a result, their populations are exploding. In just 15 years, we’ve gone from whitetail none to hundreds on our fields every night. It’s why we encourage hunting them before they reach critical mass of life out of balance. But it’s one hunter at a time. I spend time with each of them to see if they are a fit…for our vision of husbandry.

You see, husbandry isn’t just for Bessie the cow. It’s the whole picture, from earthworms to antelope. The sad truth is that we’ve only been husbands for 22 years on Alderspring, and I still feel like it’s a crash course in marriage–to the land and those that we share it with. Divorce is unthinkable after you meet a moose for the first time while moving a wheeline, or have daughter Annie come running to say she discovered some baby killdeer on their first legs. I think it would be safe to say that you could take our family off the ranch, but you can’t take the ranch from the family, because the heart of the land stays forever with us. And I hope these stories help you come along on our husbandry journey.

Happy Trails

Glenn, Caryl and Girls at Alderspring

Click here to see a video of beaverslide hay-stacking in action!

Leave a Reply