I like to look at manure. Really. In the humble cow pie is the stuff of story: who, what, when and where. Some would say that I know my manure. Now, I know there are other ways to say “I know my manure” that perhaps slide off the tongue a little more colorfully, but regardless, manure is something I look at with great interest.

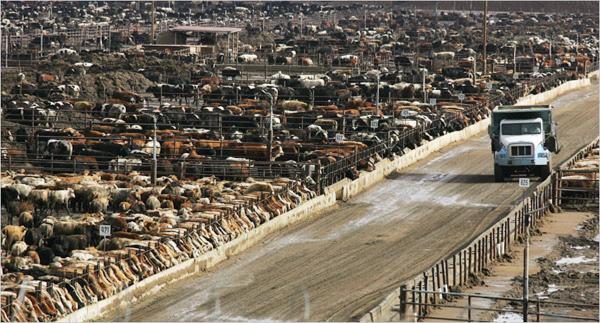

Now, with most of finish cattle in the US being fattened in feedlots (around 95% at last count), sadly, manure is something cattle feeders don’t spend a lot of time poking around with. For them, within seconds of it falling to the ground, it is a waste product to be disposed of. So they get the big diesel articulated front end loaders with the 5 yard capacity buckets, scrape it up, dripping and sloshing greenish-brown goo, and get it gone, hopefully faster than it is made, or at least as fast. I know this because I have worked there in my dark agricultural (and thankfully distant) past.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t always happen as immediately as it should, for reasons beyond me. So, essentially it is like when the toilet malfunctions, and does not flush, and the cattle end up standing in some sort of fecal soup. And in the midst of said soup, a student of scatology is unable to observe the individual deposition from back of bovine. A loss, I think.

(A sad interjection here: legally labeled “grass fed beef” can be and is more and more often now finished in a feedlot as well—some of those enterprising feedlot owners have simply replaced corn with ground-up green forage loaded into those same feedlot bunks to capture the grass fed premium.)

The feedlots often call themselves “feedyards” now, I think, in an attempt to disassociate themselves from the factory feeder stigma (a yard is nicer than a lot I suppose). In the feedyard, much more attention is given to what goes in the front of cow as opposed to what comes out. The educated nutritionists engineer cow rations with scientific precision using things like TDN (total digestible nutrients) and ADF (acid detergent fiber) in the creating of feedstuff assays. The “ignorant” laborer deals with what emanates from the back end of the cow. It reminds me of the caste system in India where entire family groups of people are designated by the rest of society as the waste handlers.

Now don’t get me wrong. We think of what goes in the front end of the cow too. But in that regard there’s a huge gulf between the cow feeder (them) and cow forager (us). It goes like this: the primary focus for us (forager) is that Bessie the Cow is ensured a wide spectrum of her own choices. Rather than shoveling corn or monocultured grass silage or green chop at her (as with feeder), she picks her own plants. And from years of observing many cows, I believe they relish the opportunity. A friend, Dr. Fred Provenza, professor emeritus from Utah State University, has published several papers indicating that Bessie knows best: in multiple studies, grazing animals that had free choice of the individual components of a feed ration gained more weight on less feed, and were generally healthier, than those fed the same components pre-mixed by an expert nutritionist in a fed ration.

I can relate from my own human experience. Growing up, money was never very plentiful. Enough food was always on the table, but it was always simple and inexpensive. I envied and traded for Twinkies and Ring Dings my friends brought to school in their fancy Superman steel lunchboxes. I brought homemade bread, cookies and fruit in my brown paper sack (there was no such thing as school lunches at that time). Both of my immigrant English-as-a-third language parents worked, and when she arrived back at home, my very thrifty and resourceful mom often cooked from scratch whatever was currently in the garden. At least once a week, she prepared a meal she endearingly called “huckmuck.”

I got off the bus and walked home the 1.2 miles. I swung open the kitchen door and me as hungry teenager who could eat several sets of parents out of house and home called out: “What’s for dinner, Mom?”

“Huckmuck.”

My heart sank. Nevertheless, famished (I thought), I took a small portion so I get through it and could clean my plate (required). I didn’t leave the table full, but at least I was nourished. It was the low point of food consumption for me out of the week. I much more relished the diverse fare of choice that Mom usually placed on our table. Even if it was mostly garden vegetables.

The closest definition to huckmuck as I recalled it I could find was this: Huckmuck: old English dialect word for the feeling of confusion caused by things not being in the right place. True story. Food particles were not in the right place in my mind when presented in the huck of muck.

The recipe was easy: Open fridge. Take every leftover container from the past week (there must be at least 6 for this recipe), and place on counter in a line. In a large bowl, combine all ingredients from every container. Stir, then mash until a sort of flecked and coarsely chunky paste is made until it becomes difficult to identify component ingredients (important). Heat skillet to medium high. Drop a half stick of margarine (yes, it was a dark time in American history) in the pan until bubbling. Dump pasty uncooked pre-huckmuck (from the old English mind you!) in pan, spread and press into a solid mat. Imagine a mason spreading mortar here. Fry until a golden brown patina forms. Flip and repeat patina. Serve hot with more margarine (it was indeed a dark time).

My brothers and I still talk about huckmuck. We abhorred the lack of free choice. It wasn’t leftovers that I had a problem with. It was that I had no control of order- the what and when-of food ingestion. I couldn’t blame my Mom. She had little time to cook and was objective driven: get the four adolescent boys fed now.

But with these cows, I’m not my mom. I don’t have to prepare anything. All I do is get them to the grass, usually on horseback in a wild and pristine landscape. The available graze has to include grass they like, with a diversity of other plants that range from wildflowers to the salty greasewood. Usually, there are 20-30 plants out there that they select from, browsing the salad bar.

To know what their preferred level of diversity looks like, we’ve spent hours on horseback, even standing among our beeves observing what they do best: grazing. It’s taken 20 or so years, but thankfully, I’m married to a PhD botanist who has literally written books about how to observe and measure range plants.

She’s a stickler for knowing the details. She has taught me the difference between bluegrass and wheatgrass, Penstemon and Parnassia. And so, I’ve been able to learn which grasses cows prefer vs. not, simply by hours and days and weeks of quiet observation as we graze them in the middle of nowhere in wild country, sitting in a saddle or on the ground in the shade of horse. I’ll try to sample the plants they prefer, on my own tongue. And more often than not, I agree with them. It goes something like this: This particular plant one has greatly mineralized flavor. Ah”¦this one has a nice maple syrupy finish. That one tastes a little salty savory.

You get the idea. It’s all about choice at the front of the cow. It’s the same paradigm their ancestors thrived in for millennia, after all. No need to feed them huckmuck in the “feedyard.” Yes. The “what goes into a cow” matters.

But I started this conversation about what comes out of the back of a cow. I’ll detain you no longer from that scintillating discussion.

My scatological interest started with several conversations with a neighbor of mine, Jim Gerrish. He lives several miles up the Valley from us. Jim is a world-renowned expert in grazing management, and coined the term “Management Intensive Grazing”, and has written several books on the subject (I’ve read them all). His ideas provide the foundation of how we manage our pastures and beeves on Alderspring. And because of his experience with animal performance in research at the University of Missouri, he and his colleagues developed a manure evaluation system that described a linear relationship to how a cow was doing on a given pasture.

Dear Reader: this was a man that knew his manure.

Jim could tell how many pounds a day a cow was gaining on grass at any point in time based the type and consistency of manure deposition with a fair degree of accuracy, usually within a half a pound. He showed the Alderspring crew how to evaluate layering in the “pie” and perform the “boot smear” test with deposited droppings. Not only could he tell me how much a cow was gaining, he could also tell me how good the grass was that was going in; both in terms of palatability with regard to species but also the age of the grass sward they grazed in.

So now, with Jim’s tool in our toolbox, each of us, even from horseback, could evaluate how well we were doing in providing the free choice that our beeves need. And every day I look at our beeves on pasture, my eye drifts down to the lowly cow pie, at any time of year. Even in winter.

It’s December now on Alderspring. Winter is slowly setting in. Our firewood is racked up by the woodstove, ready for the bleak of midwinter. Our hay pile exceeds 450 tons. Our beeves are all home now from the wild ranges and are grazing the big meadows of Headquarters. They are dispersed like black pepper over the golden grasslands of home, all looking for the last of summer green to graze. It’s still out there, although they must search a little harder. We’ll feed hay when the pasture is all gone or snow covered, but for now, they harvest their own choice from the diverse pastures before them.

They look good. Their hair coats are luxuriant. When I check on them, they surround me with curiosity and take a break from grazing. They recognize me. After all, we spent a summer together on the range. We even spent nights nearby each other; they bedded down immediately next to our cook-leanto where I would unroll my bedroll, some 35 trail miles from home. As we cooked in the late evening over the fire or stove, they would quietly watch us from their bovine beds under the pine trees, contentedly chewing cud in the lantern-light of camp.

As they visit with me on this December day, I look down, now by habit, at their recent manure depositions on the ground. Their manure is changing with the loss of green grass typical for this time of year, meaning their weight gain is dropping a little. It’s not yet enough change to start feeding hay, but I can tell we are getting close.

You may wonder why at all this thought about bettering the bovine. First, it’s about the beeves themselves. I recall a talk I presented to about 40 Idaho cattlemen about organic certification a few years back. One of the attendees spoke up during my talk and said, “our cattle are just going to get sick without antibiotics, vaccines and hormones.” He looked around the room and got his needed affirmation in the form of nodding black cowboy hats, and looked back at me, his own black and weathered cowboy hat tilted back. His denim jacket had holes in it. He made his living in the cattle business and saw organic as impossible. His statement was in a way, a question: “How do you expect us to do this when everyone else says otherwise?”

I told him our stats. “We raise and finish about 450 head of these beeves a year. Of those, maybe 2 or 3 get sick to the point we have to doctor them, usually from a respiratory infection [they fall from certification, and we sell them elsewhere].” I think they’re healthier with organic practices on carefully selected nutrient-dense grass. So, our cattle don’t get sick, for the most part. I paused, looking around the room for someone whose interest I had piqued. I knew they knew the numbers—that nearly 90 percent of beef in the grocery stores has been exposed to antibiotics. “In fact, lately, the number one cause for us to lose certification on individual steers each year is for one or two of them to get through our fence on to our neighbor’s uncertified ground. It’s not because they got sick and had to be treated. It’s because they grazed non-organic grass inadvertently.”

I thought of the antibiotic bottles I’ve thrown out, expired and unused. I always keep a bottle on hand for emergencies; we live a long way from town, and the trip to buy some new isn’t always possible or practical. Some of them cost upward of $200 per 100 ml bottle. More often than not, they end up unopened or minimally used, then pitched in the garbage, expired.

The cattlemen and women stared at me disbelievingly. There wasn’t a nod out there. They respected my opinion; there wasn’t any mockery going on. But there were no takers. These were salt of the earth men and women who weren’t going to take any risky breaks from the paradigm that we all knew offered razor thin margins. After all, the previous presentation they attended was delivered eloquently by a well-practiced and polished veterinary pharmaceutical company rep. He had shiny shoes, pleated pants, and nice professionally rendered slides with beautiful scenes of slick black cattle and scientific graphs displaying government funded research results. He arrived in a late model pickup. I just had a white board detailing my experience, wearing my best faded wranglers and cowboy boots. My ride was an 18-year-old pickup.

There’s no government sponsored research to tout the benefits of artisanally stewarded wild grasses managed organically.

The second reason we spend so much time bettering the health and performance of our beeves is because of you. You have entrusted us to grow the best beef. Not only in terms of flavor and tenderness, but nutrition. So we spend a lot of time hacking, fine tuning the efficiency of beeves living in their native habitats of free choice. A steer that is growing well and performing well on wild landscapes is going to be nutritionally balanced. And that’s better for you. And that makes all the difference, because you have trusted us with your wellness and those of your loved ones. And hopefully, you and yours will live longer because of it. Like Alderspring cattle.

Happy Trails.

Glenn, Caryl, Girls and Cowboys at Alderspring

Leo Younger

Fear of failure is preventing many ranchers from truly benefitting themselves and their customers. I guess their fear also prevented them from signing up to get on your email list to read these posts. Thanks for the info regarding manure. It brought to mind Charles Walter’s book, Dung Beetles & A Cowman’s Profits, 2007. Amazon’s book description begins as follows: “Dung beetles have always been nature’s greatest recyclers – in a way, they were the first organic farmers. They were also the first casualties of industrial farming. As farmers rediscover the many benefits of grass-based livestock production, dung beetles are given a solid shot at reestablishing their rightful place on the farm and ranch.” In his book, he mentions the fact that dung beetles are harmed by the chemical parasite controls used by farmers and ranchers who use such products.