August on the high ranges ushers in a slow, almost imperceptible transition from summer to fall. The nights are already cooling, and by the end of the month, we will have a frost, and the beginnings of snow dustings on the highest peaks. My ears stay tuned for the sound of elk bugling—the definitive herald for the onset of fall. Yesterday, geese formed up in a ragged V, as if squaring up youngsters on their first training flight, in prep for the big run south. In spite of spending many summer days and nights up in the Hat Creek country, I always have the resounding feeling that I am only a visitor.

It isn’t that humans never found permanent residence there. I’ve always figured that Native Americans lived there, but I knew nothing of them. I could find no records specific to the breaks, peaks and canyons that defined upper Hat Creek. Then, one fine spring day, some 25 years ago, I was working on a fencing project in the Lemhi Valley with an old Shoshoni. We struck up a conversation about ranching, and I told him that I had been riding for an old cowboy, Ed Corbett, in Hat Creek. He knew a little of the country, and stopped and looked me in the eye, heavy wooden post on his shoulder.

“Do you know why they call it Hat Creek?”

“No.” I stopped and put down my post, and looked up at him. “I guess I always pictured someone losing their cowboy hat up there…and someone else finding it in the water or on a rock or something. You know”¦in the creek”¦soaked.” I smiled. He didn’t.

“No.” He looked at me stern faced for what seemed like an uncomfortable 30 seconds. “It is because the Bear Hat tribe lived there. They wore hats made of bearskin. They were their own band, separated from other Indians by the rocky canyons that formed a fort-like wall from the other peoples. They had been there as long as any of the old ones could remember. You whites know nothing of these people. You have dropped the ‘bear’ part of the name, and call it only ‘Hat Creek.'” He turned, and walked away, post on shoulder.

It stuck with me over the years. No one else I have met spoke of these people. Yet, there were things that made sense. First of all, there are many bears in the country. Cowhands Ethan, Abby and Linnaea just bumped into one yesterday, feasting on chokecherries that are now laden with fruit in the creek bottoms. Bears indicate a land rich with productivity that can satisfy their omnivorous appetites. The ubiquitous presence of ursine friends lent stock to my Shoshoni friend’s hatmaking story. Simple logic: many bears made for plentiful hats.

Second, I have found evidence of prehistoric peoples—likely the Bear Hats–throughout the labyrinth of canyons and peaks of Hat Creek. I picture them living year round up there–a hardscrabble existence one would think, but after spending years of summers up there myself I now have an insider’s view of just how one could not only survive, but thrive. Hat Creek boasts fairly abundant animal populations. I still often spot bighorn sheep in the craggy cliffs of Little Hat; they were abundant before domestic sheep brought disease that largely wiped them out. Isolated groups of bison and deer roamed throughout Hat Creek. I’ve found numerous pit blinds where native hunters would lie in wait where canyons joined to ambush game as it walked by.

But protein hunting wasn’t always easy, and was often feast or famine for the indigenous. After years on horseback and living with a bride who is an ethnobotanical expert I now see that there is food everywhere in the plants of the range, and all it would take for one to make it on the land was knowledge of what they are and how to prepare them.

A plethora of roots and berries thrive in the rich volcanic soils that comprise the country. Even on the drier landscapes bitterroot, Sego lily bulbs, and wild onions can dominate hillsides. Many of these would easily be dried and turned into flours that could sustain in the winter. Several cacti with edible fruit thrive in the lower elevations and numerous potherbs live in both dry areas and riparian areas. Even for me, a non-native, I feel like I would never go hungry up there, given knowledge of the native plants.

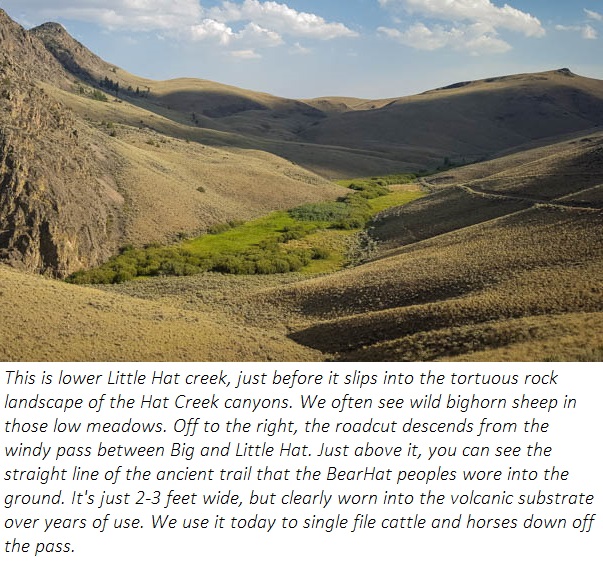

Just yesterday, while riding out of Big Hat Creek, Caryl and I noted a sizeable trail coming off the windy pass between Hat Creek and Little Hat, above where their rocky canyons join together into the main Hat Creek drainage to the Salmon River. It was an ancient superhighway, purposely made straight by humans with direction in mind (rather than wandering and foraging game), and made broad and worn into the hard volcanic substrate by centuries and the great number of Bear Hat travelers first on foot, then on the Spaniard’s legacy of horseback. This was probably a trading trail that brought out abundant yields of beaver pelts, or the ubiquitous agate core stones that litter the volcanic breaks of Upper Hat Creek. These would be valuable to other native peoples as a foundation for weaponry arrowheads and spearheads in the ancient art of flintknapping.

I’ve found perfectly knapped and deadly sharp arrowheads in Little Hat Creek of such volcanic agates. I recall one day I was looking for strays alone, far up in the wilds of Little Hat. I was horseback, walking up an elk trail along the willows very slowly, looking for a stray beeve in the brush. I happened to peer in front of us at the trail in a given moment, and spied a point right under my mare’s nose in the middle of the trail. I jumped out of the saddle and stooped to pick it up. It was a large and perfect blue green agate point, completely uncovered, about 2 inches long, with carefully notched sides that allowed it to be lashed to an arrow shaft with rawhide. It was as if the owner was just ahead of me, stalking for bighorn sheep, or bison, and dropped it out of his buckskin satchel. I felt an impulse to check the trail dust in front of me for a moccasin print—or the small hoof print of an unshod mustang. Time didn’t stop for me there—it rolled backward 300 or 400 years. Was he perhaps stalking a bear occupied by the chokecherries below that were laden with fruit in early August? Our hunter likely was browsing and stripping some of his own fruit off the branches as I do whenever I ride by. It could be that he needed a bear for a new hat; perhaps for a mark of position in the peoples he lived with. I’ll never know. But as I fingered the point in my palm, the possibilities rolled through my mind like a movie.

I’ll never forget the time I was watching Pacific Ocean steelhead spawn after their 900 mile journey up from the ocean all the way to the lower Hat Creek canyon. In the clear and fast moving water, I could see their 3 and 4 foot long shapes excavating gravel nest beds, or redds, for egg deposition. Cataracts and waterfalls stopped the leviathans in their seemingly unquenchable desire for farther up and further in. I thought that perhaps the Bear Hats did not fish by net or pole, but by hunting the big fish with arrows and spear. After all, hunting was what they did throughout the year in all the tributaries of upper canyons because there was little to no fish up there. There certainly was not enough to warrant the time it took to make nets, and perhaps bow and arrow would have been the most efficient way to secure salmon protein.

As I watched the big fish, something caught my eye. There, on a huge rock overlooking one especially large pool in lower Hat Creek, was a greenish looking item that stood out from brownish red of the gabbro boulder I stood on. I bent over and picked it up, turning it over in my hand. It was an arrowhead, perfectly designed, and made completely of copper. It looked manufactured.

A little research back home quickly yielded the information that that copper points such as this were made in large quantities in 17th and 18th century Europe simply for beaver pelt trading with native North Americans. Companies such as Hudson’s Bay Company provided keg loads to their trapping networks as cash for pelts. I thought of the journey this arrowhead had undergone to end up here, on this rock in the mountains of central Idaho. It likely was mined in 1600s England, France, or Switzerland. Then it was made into a point in sweatshop-like copper foundries in London or Paris and loaded into casks on Hudson’s Bay Company ships bound for the New World. It could have found its way west in Voyageurs’ canoes across 3000 miles on lakes and rivers of Canada to trade directly with beaver fur trading tribes in the Pacific Northwest. Or, the American Fur Company could have easily picked up the copper heads on a wharf in New England, shipped them by river route across the heartland to St. Joseph Missouri, and then by wagon into the far west. This would have happened a little later, perhaps, in the 1700 or 1800s. However it found its way here, I find it ironic that a Bear Hat hunter carried a point traded only to acquire beaver hats for elite aristocratic gentlemen some 9000 miles distant in high society western Europe.

Eventually, the Bear Hats succumbed to the same fate as all native populations did: occupation and conquest. But up to that point, these people made a life and culture founded on the same rich volcanic soils that we now graze. In a sense, we live on their legacy, as the same wildly productive soils that sustained them through season after season of brittle winters sustain our beeves with a robust health not found often in the bovine world. After 12 years on those ranges, I have yet to see a sick animal of ours out of some 2500 head that I have put up there. We’ve given them only sea salt as a supplement. And they have thrived.

All that sustained the wild protein that those Native Americans thrived on still exists on our ranges, and even on our home ranch, because conventional agriculture’s practices of soil mining have never been employed here. And that is why we can offer you flavor and the nutrition that comes with it, in our protein from the wild landscape. And you don’t even have to carefully knap that piece of agate into a finely honed point (or drop it on the trail!). No marksmanship needed.

We do that for you. And, as a bonus, we provide you the story of how your protein-our beeves-forage in this wild landscape. I hope it makes your eating and wellness experience with our beef richer, and more connected to this place we call Alderspring. I hope I can communicate with you how intricately woven together our work here is with the natural landscapes we call home, and how much I love this mountain country here in the middle of nowhere, Idaho.

Thanks for joining us in the story and the journey.

Happy Trails

Glenn, Caryl and Girls

Alderspring Ranch

Leave a Reply