Let’s roll back the clock 34 years, and I’m still me. Instead of my 2021 gray, my hair is the dirty blonde that goes with my blue eyes of Dutch ancestry. I’m working in the forests in the steep and rocky mountains of Central Idaho. I’m in great shape from hiking up and down at elevations of up to 10,000 feet in my timber work, planting trees, thinning ones that are too thick, and fighting fire when lightning strikes.

I supervise a forestry crew of up to eight people. We work in the middle of nowhere; often, we drive rough logging roads for nearly two hours to get to the piece of forest we labor in, measuring (we call it cruising), thinning, prescribing, mapping and planting. There is no one else out there.

Wildlife is abundant. Elk, deer, bighorn sheep and mountain goats share the land with us. We meet bears, eagles and hawks. Mountain lions watch us. I love them all and am left in wonder when we encounter them.

But there is an animal that I run into frequently—perhaps most frequently—that I absolutely have come to abhor, despite much of my upbringing being around their much-loved milk-producing cousins. They are beef cows. Domestic bovines. I meet them in the semi-wild forests that we work in. Their owners have left them completely on their own, grazing on their wide-open summer ranges until October. They can wreak havoc, camping in creek bottoms, crapping in streams, caving in banks. They rub the bark off trees, eat new growth, and trample my new plantings of Douglas-fir and lodgpole pine seedlings.

It’s cows behaving badly.

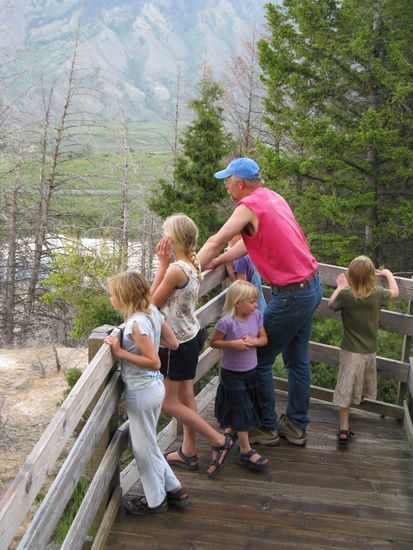

Now, It’s 1997. Caryl and I frequently visit Yellowstone National Park. On this particular foray into the park, we’ve got two little kids in tow, or rather on our backs. Their weight is rather insubstantial compared to the heavy books I often carry for my wife. One title is actually a 5 volume hardcovered set, and they are all large. It is Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest.

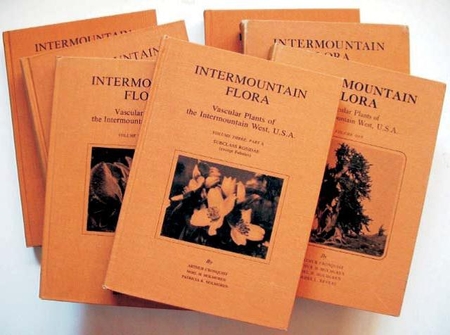

They’re a sort of foundational reference for botanists for our area. They have dichotomous keys in them, a series of if-then statements based on physical characteristics, some only identifiable with hand lens, that allow the user to conclusively identify nearly every plant in the Pacific Northwest. Sometimes she’ll take the shorter version in one big volume, and sometimes she’ll also bring a more recent set, the Intermountain Flora (also multiple volumes- see why I stay in good shape?).

On this trip, she’s taking it easy on me, bringing only the big single volume and a thinner book to live with us in camp. She comes on a quest. Each year she picks a difficult genus or family of plants in our area to work on. This year it’s willows, the Salix species in our area of Idaho. She’s identified most of the 23 species in the field, using that thinner book- a book about willows and nothing else. To me that she can confidently name them is fairly remarkable; first, willows can look very much alike with their elongated leaves and similar fruiting bodies, and second, she tells me that Salix trees and bushes are somewhat promiscuous and commonly interbreed.

She is excited about her recently acquired Salix savvy, and brings it happily to Yellowstone on this fine fall day to test it on the species found on the broad Park plateau. We journey to the northern tier of the Park first—it has the lowest tourist load, and we hope the early colors of autumn will greet us up there in the higher elevations along the edge of the already snow-sprinkled Absaroka Range.

But then, disappointment strikes. The willow hunter finds little of her quarry. Even the broad Lamar River was conspicuously devoid of them.

Flashback to the mid 1980s. Caryl was working as a plant ecologist and I as a forester here in Idaho. She’s been spending most of her time working on grazing allotments, measuring deteriorating plant communities in both upland range areas and in riparian areas along streams. After a trip to Yellowstone, she remarked to a wildlife biology colleague that she thought the condition of Yellowstone streams looked very similar to the ones she worked on. He replied that was impossible because Yellowstone was a natural system.

There were no cow culprits in the Park.

Or were there?

It gets a little complicated. Wildlife managers in the Park recognized that riparian vegetation was in trouble even in the mid-1900s, and at that time, elk were to blame. As a result, in 1995 and 1996, wolves were released into the Park to get a natural handle on elk populations. As you likely know, that wolf introduction program was wildly successful, and in many areas of Yellowstone, stream side vegetation like willows and aspen took off due to the lack of browsing (grazing) by the antlered ungulates.

But wolves really don’t have interest in bison. Bison are formidable, with males and females both equipped with large horns. They know how to use them and can readily skewer even a large wolf on the attack. Bison can sprint up to 40 miles per hour, and a protective mother is pointy horns on steroids.

Because they were left alone by both wolves and grizzly bears (for similar reasons), bison quickly filled the elk niche on woody vegetation, particularly on the open ranges of the northern tier of the park. Today, there are over 4,000 in Yellowstone, up from under 100 in 1900. This becomes even more interesting when reading some present-day experts who believe that there is little evidence that significant numbers of bison inhabited the park prior to its founding in 1872.

But they are here now, and iconic as they are, will certainly stay.

Who knew that Yellowstone National Park and ranges throughout the Intermountain West would have identical problems with bovines? The same cattle issues I had been seeing in the 80s and 90s on public lands grazing allotments that overlapped with areas I managed forests on were being repeated by bison in the Northern Tier of the Park. In both, creek-side margins, or riparian areas were muddied by big cow prints and the new growth on willows and aspens was eaten off.

Some would argue that perhaps this is the natural state. Yellowstone, after all, is supposed to be in a “natural” state, unaffected by people. But this ignores both history and ecological reality. First is the dramatic increase of bison in an area that may historically have had only incidental occupation. The mountainous area of Yellowstone, and the plants and ecological systems there, are very different from those of the Great Plains, where the interaction of plants and bison was mutually beneficial. Also, wolves were completely removed from Yellowstone by 1926. That is over 70 years without the keystone predator to control grazers. The high populations of elk over several decades dramatically changed the Yellowstone ecosystem.

It’s now February 17, 2021. Caryl and I are planning this year’s grazing season for the Alderspring herd. It looks like we’ll be putting over 400 head of our cattle again out into the summer ranges of the Hat Creek Country. Much of the landscape is very similar to that of the Park, which is less than 200 miles distant. Hat Creek ranges from 4000 to nearly 10,000 feet and is a 70 square mile fairly intact native plant landscape founded on volcanic ashy origins, as is Yellowstone.

In addition, we have wolves. Lots of them. There are more than there are in Yellowstone. In addition, we have tons of elk, but the numbers have reduced due to wolf predation. The wolves got us to think completely differently about how we graze, ever since 2014, when we lost 14 head of cattle to predation. Good news thereafter, though. Since 2015, we have lost 0. What happened?

Many of you readers already know this, so I won’t go into great detail. In simple terms, we started living with our cattle in remote horseback camps and herding them. We weren’t shooting wolves; we only stood as a human presence with our cattle. Caryl and I had spent time with wolves in the Canadian north country. One thing was clear: they had little use for humans and would quietly leave rather than spend time with us.

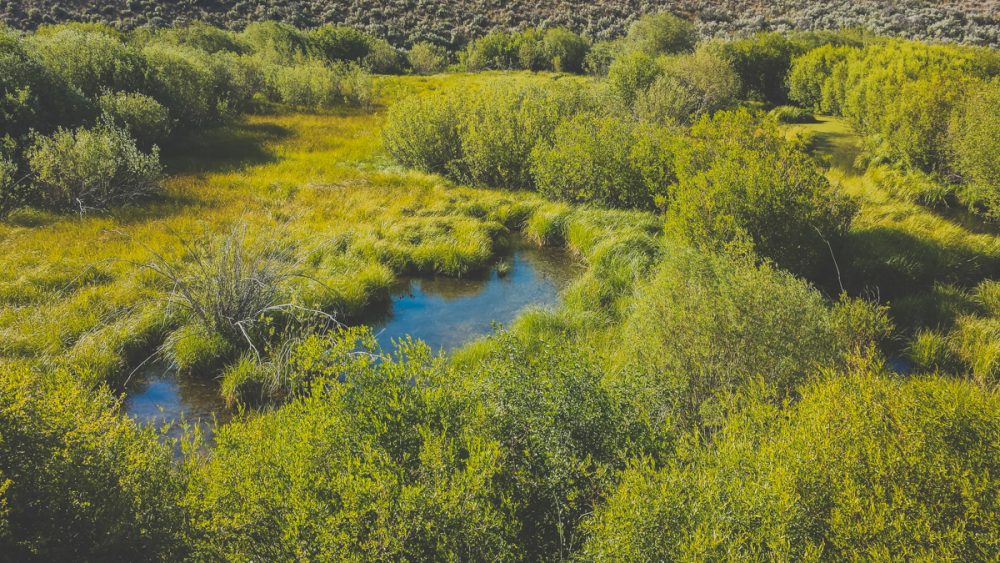

The plan worked for wolf predation. But even more interesting to us was the complete game changer for our riparian vegetation, once we relearned the ancient concepts of herding. We found that we could easily direct the cattle away from watercourses and fast track regeneration of those habitat-rich areas.

Caryl, ever the monitoring guru (she co-authored Monitoring and Measuring Plant and Animal Populations, published by Blackwell Scientific, in the early aughts) created a protocol by which we could estimate grazing and bank alteration impacts caused by our cattle. In one year, and every year thereafter, we went from 38 miles of stream bank disturbed or grazed by cattle to less than 350 meters (out of 55 miles). From a percentage standpoint, we went from 65% of our stream miles affected by our beeves to less than one percent. The only exception was last summer, when we relaxed our inherding protocol experimentally, as our riparian area aspen and willow regeneration had grown above the hungry reach of our cows.

So here is why I’m thinking about Yellowstone, my ruminations started by an article I read about beavers, bison, and Yellowstone.

You see, there are only relatively few beaver in Yellowstone because there is little to eat. Same as my bride was disappointed to find few willows to try out her new expertise in identifying them, beavers are disappointed in a more significant way by a lack of food.

Yes, beavers graze on grasses like cows, but foundational in their diet is willow and aspen twigs. In winter (they don’t hibernate) their grazing occurs silently under the ice of their pond created by a dam of their own design. Even kits dive down with their well-insulated coats, easily able to hold their breath for 10 minutes or more. A second set of lips behind their front teeth prevents water from coming into their throat as they nibble on their woody storage larder.

Beavers are key in our mountain riverine systems. Their dams disperse stream energy, keeping the stream from eroding its channel. By raising the water table, beaver widen the ribbons of green along mountain streams, increasing habitat for all the many birds and animals that depend on these areas for critical habitat.

On our ranges, we had to completely exclude cattle for several years before the regenerating willows and aspen exceeded the height that a grazing cow could reach. With inherding (that is what we coined our cowboy meets sheepherder paradigm bringing together intensive and intentional herding), we had a tool to control cattle use. And after several years of rest, woody vegetation reestablishment is abundant.

We knew that beavers were historically, and prehistorically present on our ranges, as the shadows of their dams and lodges still existed when we took over Hat Creek in 2005. But there was not a single one anywhere to be found in the 70 square mile area.

In 2018 I spotted my first beaver, and now there are several active colonies. But we had to build it before they would come. It was not until we controlled our cattle (and the wolves controlled the elk), that the streams got enough rest to recover.

Even in the short time the beaver have been working on Hat Creek, we’ve seen changes. We now have creeks going from ephemeral to perennial. We have non-native dried out Kentucky bluegrass flats being replaced by native Nebraska sedge and Baltic rush as water tables rise again. We have difficulty in locating steel monitoring T-posts for repeated photopoints because the willows have taken off so densely.

I’m thinking the beaver are going to create a coppice, or tree farm culture (they have actually been shown to be intentional farmers of willow and aspen) that would allow us the luxury to continue inherding with a move to a little less intensity. And hopefully, we’ll create a regenerative, ecosystem recovering model that is also an economic one for cattle producers on public lands throughout the West, as the cattle gain weight better when herded intentionally than they did languishing in a hammered riparian area for the summer.

With vegetation run amok comes of course, carbon storage. It is one of the reasons Alderspring is climate positive and carbon negative. I wish all ranchers would jump through this window of opportunity.

I’m not a believer in silver bullets. But my disdain for all cows has finally ended with inherding. Instead of agents of disaster, we’ve used cows as a positive force for vegetative change, managing them as a tool to fast-track nutrient cycling, soil organic matter and plant diversity. And carbon storage.

What about Yellowstone? Inherd bison in the Park? Pretty unlikely. The park has long been an advocate of “hands off” management.

For now, tourists will not know that habitat components like woody vegetation along creeks is absent in parts of the Park where bison congregate. They won’t know why the Lamar River can run muddy. And they won’t know why songbirds and beavers are largely absent from much of the park’s watercourses. And maybe that is OK. But I do find it ironic that it appears as though it is easier to regenerate habitat outside of the Park than inside its boundaries.

But we’ll know when the lazuli bunting and mountain bluebird return to nest in brush and trees that we helped establish that we are doing the right thing. We’ll quietly watch beavers stage a takeover of all 50 miles of creek on our range, causing once dry creeks to run again because our cows no longer compete with beavers for their preferred foods of aspen and willow.

And it will bring me joy. I hope the same for you.

Happy Trails.

-Glenn

Pat Boice

Wonderful story!

Caryl Elzinga

Thanks so much, Pat, and thanks for reading!

Alice F Engle

HI ALDERSPRING,

I SO ENJOYED YOUR ARTICLE. AS ALWAYS….MANY THANKS FOR BEING SUCH WONDERFUL STEWARDS OF THE LAND AND TEACHING US HOW TO CARE FOR THE LAND THAT HAS BEEN ENTRUSTED TO US. I LOVE THE PHOTOGRAPY, TOO.

GOD BLESS YOU ALL! 🙂

ALICE ENGLE

Caryl Elzinga

Thank you so much for reading, Alice, and for such kind words!

Gene Haire; Corvallis, Montana

Very much appreciate your family’s work and your stories. A very bright and hopeful spot in a sometimes dubious world.

Cameron Schlehuber

Inherd bison in Yellowstone Park? I hope it won’t be so unlikely. After all, wolves have been purposefully reintroduced, and people are already present in the park, why not have park rangers (and visitors) riding on horseback close enough to streams to help keep the bison a bit further away from the streams? If some in congress can recognize the science that is being demonstrated in the Hat Creek area and that bison were rare in the early days of the park, perhaps some intelligent direction can be applied to park management.

Glenn A. Elzinga

Cameron:

I’m so glad you agree that it is worth a try! Your methodology is exactly what I would try first: why not attempt to train bison via herding away from creeks that browsing in those areas will be met with resistence?

But herein lies the problem with such a proposal. There is a majority in Park supporters (even in their admin) that have as a core value to leave things to nature. Obviously, as you point out, we have intervened time and time again with wolf reintros and culling elk and bison (and originally extirpating predators), but they must see those kind of interventions short corrections instead of a proposal like ours that would conceivably require continuous input for several years until vegetation reached critical mass.

The other problem exists that bison browse some of these plants in midwinter. Although it sounds fun to me to be horseback or on skis in the winter moving bison around, I think you would be hard pressed to get park buyoff…and find other people crazy enough to do it!

Perhaps we have to trail the bison out of the park in midwinter to lower ground as the elk do (they all migrate south to Jackson, WY). But then we could leave wolves without a meal of the expected occasional winterkill bison that they feast on.

It’s complicated, as you can see. But I do agree with you that something needs to jumpstart the ecosystem out of the gridlock it is in! Check out Google Earth sometime in the Lamar River Valley. There you can easily see that there are miles of banks exposed and devoid of stabilizing woody vegetation. Then, check out any western river outside of the bison realm, our own Pahsimeroi, for one. The difference is incredible.

Sara Reilly

Thank you for restoring the reputation of cows – they have been unfairly demonized for too long, in favor of their wild counterparts!

Michele Gordon

I did so enjoy reading this article! Thank you for all this information. We live in Michigan and I wish we lived closer to Yellowstone National Park!!!

John Madany

When I look out my office window I see willows along Blacktail creek. I thought they would make a good coppice. Good to know beavers have already figured it out.

Bob Traeger

What a fun and informative read. Thank you for sharing.