This week’s story is from one of our summer conservation riders, Jessie Maier. Jessie came to us from Paicines Ranch in California, where she had worked primarily with sheep. Her goal for the summer was to improve her stockmanship and learn about conservation herding and regenerating landscapes. Mentoring young range conservationists is an important part of what we do, and we get to meet some great young people!

The Turning Point

Our third stint out on the range is when something changed. A couple of switches flipped and I was like yeah, I can do this for the summer. Up to that point I’d really been struggling. The long days sitting in the saddle, exposed to the elements and watching cattle eat were getting to me. I think it was this combination of things:

First, my stockmanship improved. All those hours that I’d felt like a was going crazy I started seeing lines on the beeves’ bodies (Maybe I was going crazy!) at their point-of-shoulder and down the center of their backs. I’d experimented, riding into the cattle at different angles and watching their responses. And all of a sudden, I could get them to do what I wanted. There was one moment I’ll never forget. We were grazing around Mitten Camp and I was alone at the front of the herd. We were on the side of a hill, trying to keep them up out of a draw below on the grass that hadn’t been grazed yet. I rode against them at an angle to their shoulder. One-by-one they turned up the slope, their bulky bodies defying gravity. It was hypnotic watching them turn with almost assembly line precision.

Second camaraderie amongst the crew improved. We were going through thick and thin together figuring out how to come together as a team to keep the herd together. At the end of everyday we’d debrief, going over what could’ve gone better and unpacking any problems we had with others’ communication, leadership or herding techniques. Then we’d move on, all forgiven, and share our cooking experiments, give the horses creative hairdos and listen to Anthony’s poetry.

Finally, I learned to pace myself and that the ‘little’ things are really the big things. Until I figured this out, the days were a long, uncomfortable, boring blur. But knowing what to expect and expecting that everything will take longer than you think it will improved my acceptance of the rhythm of the days. ‘Hurry up and wait’ became my mantra. I started breaking down the day into manageable parts in my head and found something to look forward to in each part.

- Go for a run. Alone. And watch the sun rise over the mountains.

- Breakfast and coffee. The best meal of the day!

- Find out which horse I’m riding. Catch them, saddle up and mount up. No matter how sore I was, the feeling of being back in the saddle, elevated over the cattle and feeling my horse’s powerful body beneath me was a good one.

- Wake up the cattle, check them for health problems and count them.

- Take the cattle to fresh grass and get them their breakfast.

- Water break and snack time.

- Afternoon graze. Around 3 or 4 a breeze usually picks up. Then around 5:30ish the light starts to get really beautiful.

- Back to the night pen. Having a destination to go to is a great feeling and we got to see some pretty spectacular sunsets and moon rises.

Does doing chew make me a real cowboy?

One night after a long day and coming into camp I was offered chew. I’ve always thought chew was a disgusting habit, but I’ve seen and read about so many legit cowboys doing it that of course I had to try. It tasted amazing! It was mint flavored. Like gum but a thousand times better. I went from stressing out about other crew members staying at the back of the herd and worrying about not making it to the night pen before dark to completely relaxing, enjoying the sunset and relishing in that perfect moment. I could see myself getting addicted to this. Unfortunately, but fortunately, about an hour later I felt nauseous. My stomach tied in knots and with each step my horse took my skull throbbed. I’m going to have to pass on that aspect of cowboy culture.

Nightpenning

Around 7, when it’s time to take the cattle back to camp is when the day turns sublime. A cool breeze picks up and feels like sips of water against your skin after the intense heat and sun. The cattle move as a cohesive unit, heads down, grazing, all moving forward at the same pace so that all you and the crew have to do is float along the edges. The light changes and the hues of the wildflowers become saturated and the sagebrush and the Salmon River Wildrye turn silver.

That feeling of we’re really doing this

Eight days is a long time to be living with the cattle. It was the final day of our stint and it was full of miscommunications. All my physical and mental energy was spent. My butt ached. My hair was a solid, itchy mass under my hat. Every time a beeve strayed from the herd and I had to move to go get it I stuffed a meat stick into my mouth for revenge. We were moving camps that day and kept stopping, watching the horizon and listening for the whinnies of fresh horses signaling that the new crew was on the way to relieve us.

It was after 6 when Anthony finally said that we should head for the new camp if we wanted to get there before dark. We were on top of a ridge with a view down the entire valley. High peaks surrounded us in the distance. Ashy cliffs, jags of bare rock and stands of timber stood closer at hand. The hills we’d already grazed spread out below us. I felt a strange mixture of exhaustion and awe.

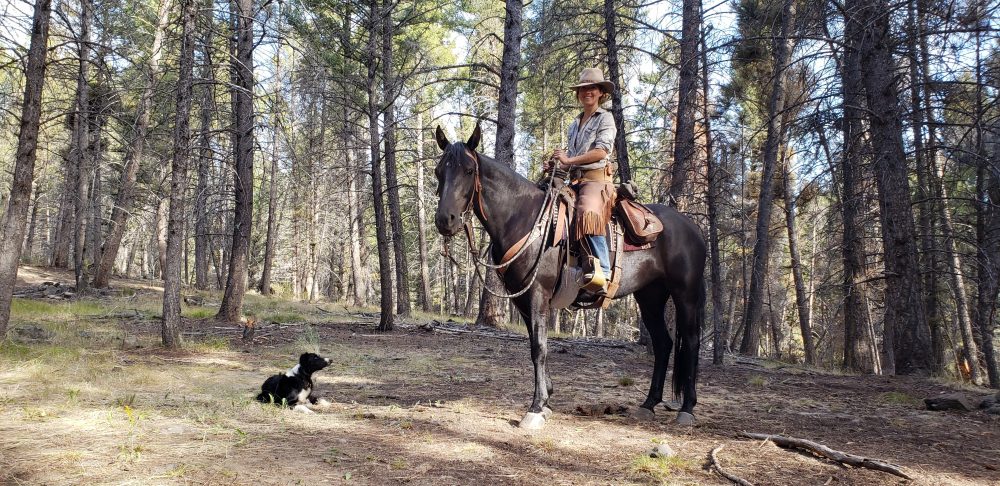

We’re really doing this. We’re these little monkeys riding around on a thousand pound prey animal that we’ve tamed and trained, feeding and living with another prey animal that will eventually feed us. And Kip, my collie was there. He’s a predator who is the result of generations of breeding, stories and bonds between his ancestors and other ranchers, and who, because I’ve established myself as pack leader, respects me enough to watch my body language and move the cattle accordingly. And there’s nowhere else I would’ve rather been. I felt honored and privileged to be a part of this herd, this crew, this land.

What I learned

Grazing native range is not the same as grazing pastures or rangeland that’s been taken over by invasives. When I think about grazing, I think about succession a lot. I often find myself making the assumption that there’s some optimal successional state that nature is working towards or wants to settle at even though in my gut I know that this is incorrect. In California I assume that if people hadn’t come in and screwed things up, the hills would be covered in oak trees, perennial grasses and an astounding diversity of forbs. Maybe, but maybe not.

Is this the desired landscape I should be basing my grazing decisions on? The bar by which to measure success? I don’t know. And coming into a totally different landscape, and one that varies so much with elevation, threw me off yet again. For all the time and energy we spend up on the range, I want a better understanding of our grazing practices- the how and the why for ecological benefit and maximum weight gain. I understand the basics, like keeping cattle out of riparian areas, grazing grass at the right time to maximize carbon sequestration, minimize erosion and not to diminish perennial grass populations, but nature is so complex! Back home, for reasons I will probably never know, from year-to-year I’m constantly noticing different plants popping up in different spots around the ranch. Some are consistent, despite our attempts to alter the plant community, and other plants I’ve never seen before will come up in areas untouched by us. Is it the same here?

In applying this to our own human lives I think that this means there is no plan, no final pinnacle of status, accomplishment, or knowledge. There is only constant change and from this, growth.

Part of that is learning how to cope with boredom and discomfort. Part way through the summer I began to realize that discomfort makes me feel alive, and by pacing yourself, being grateful for the ‘little’ things, boredom becomes less of a problem.

Spending long days herding taught me several things about stockmanship:

â— Your herd is only as fast as your slowest animal

â— Cattle can be blown by the wind

â— How herd movements influenced by topography

â— How to slow down and how to settle the herd

â— How to be a caretaker. Taking care of animals means putting your needs last. After the cattle, after your horse, after your dog.

â— How to get cattle to go uphill,

â— How to herd through the timber

â— How to change their mind (follow through and acting like a predator)

â— How to cross draws and go down slopes

I also learned new and improved horsemanship skills:

â— How to prevent saddle sores

â— Groundwork

â— Basic riding exercises and why they’re important (backing up, yield the hindquarters and forequarters)

â— How to catch a horse

This job is hard work and it’s not always fun. It’s hard not to start resenting 300+ head of cattle when you spend all day every day putting their needs before your own. It made me question if I’m really as passionate about land and livestock as I thought. But no matter what trials and tribulations we went through, getting back in the saddle the next day always felt good and I was ready for the next adventure.

terry young

It was great to see you guys up the mountain where you had “parked” the cattle. We were most impressed with what you were doing with the cattle… and the land….one of the many highlights us Australians had on our trip around your great country-side. All the best. Terry and Rose…Sth Australia

Merrianne Hackathorn

Wonderful story–so well written. Well done, Jessie! And the photos are fabulous!

Ros Rees

So well written Jessie what a great insight to the life of a conservation rider. There is always so much more going on behind the scenes , that one can capture in a moment of a conversation.

Your astute observations and willingness to see and understand what can be possible is to be admired.

Was a real pleasure to meet you and Kip on the mountain.

Keep following your passion

Ros Rees

.

Rick Cameron

A delightful and sentimental read, thank you Jessie, Graeme and Ros. As a lifetime shepherd in southern NZ being responsible for up to 6,000 heartbeats every day 24/7/365 for 30 of my 44 years ownership , (sometimes 11,000 heartbeats ), on a 2 wheel bike instead, with a team of dogs and staff to put before myself, I too love everyday’s sun, cloud, wind and rain. The regenerating mindset and the ultra high density grazing are just a wonderful addition. As if a spirit with the land connects us all regardless of the continents/islands we occupy. Your story inspired such a reflection, excuse the waffle. Keep up the writing, you have a heap of potential to teach the disconnected city we need.