I yanked on the stubborn cheater bar to no avail in an attempt to open the rickety gate in the barbed wire fence. Caryl would just love this gate, I thought. The cobbled together fence marked our property line with the BLM; it was probably easily over 60 years old. Many hands had fixed on it over the years and redneck cowboy logic had prevailed through most of the fixes. Like most of the older barbed wire fences on the ranch, it doubled as a sort of museum display, and it told the history of barbed wire evolution over the past century.

I yanked again with a more directed pull, this time squarely placing the full leverage of the wooden bar against the tense wire gate. The stubbornly coiled spring of barbed wire sprung, and the 4 strands of barbed wire gate fell into the mud. I stepped through the opening, and after a few steps slogging uphill, I resumed my conversation with Mike, the BLM Real Estate Specialist guy that accompanied me: “It isn’t that there is only one barb wire fence up here, Mike. There are three for those elk to jump over, all within a distance of 75 feet. It’s ludicrous.” I pointed up the hill, and as I described, there were two more 5 strand barbed wire fences bounding the road that continued up the hill across government land.” See what I mean? When those elk come down for some thermal cover in the valley bottom here when winter winds really start howling, they gotta cross three fences.” I picked my way through the thick sagebrush while waiting for his reply.

It never came. I turned around to where I thought he was, and he wasn’t. Instead, he was still standing on the other side of the open gate, watching me soliloquize myself into the distance. “What are you doing?” I asked. “You comin’?”

He slowly shook his smiling head. “No. I’m not.”

“Why not?”

“‘Because I can’t step through this gate onto that ground. It is sacred.” His face turned serious.

I just stared back at him, wondering if he was for real. My eyes drifted beyond him to the hills. The snows were finally pulling back with the onset of spring; it was snowdrifts only, occasionally stretching across the road Mike and I had just walked up. Moist soils were erupting with green grass and the birds sang with spring rhapsody. It was one of those Kodachrome spring days with deep blue skies contrasted with blindingly white snow on the hills that surrounded the valley.

As Mike was a BLM Lands Specialist, he dealt with the private/public land interface for the Agency. He was also Shoshoni by blood; his heritage was clearly announced first by his long single braid of black hair that emerged from the back of his ball cap and the square-jawed face of many Shoshoni. We had been climbing over deep snowdrifts together, postholing deep tracks in the wet slush that indicated that it wouldn’t be long now; soon, the snows would leave, and spring would turn to summer. I had brought him up here to see if the Agency could do something about all of those fences. At least one elk had died there this winter, catching feet in barbed wire as the herd crossed in deep snows. It was like a WWI no-man’s land between armies entrenched in battle; too many obstacles claimed one of the many that tried to hazard their way across.

One elk high strung by wire was too many for me. I knew there would be more. Just a few weeks ago, I found a yearling elk hung upside down in the twisted wires of the fence. I was sure that he was dead until I witnessed a sudden eruption of movement as he struggled to get free. As I ran through the deep snow to get to him, I grabbed by trusty pliers out of my pocket; with those, I could sever the wires that held him in bondage. Just as I came up to him, he spotted me, and the sheer terror of seeing me, the top-of-the-food-chain predator up close and personal delivered the goods that were just what he needed: an adrenalin lunge that jerked his feet free. And he was gone in a cloud of cold white powder snow as he skipped into the deep brush that cloaked the fenceline farther up.

I’d seen places where barbed wire took its toll on not so lucky elk and deer before; occasionally, I’d spot the dried and jerkified skeletal hind leg of a deer or elk quietly swinging in the mountain breeze as a testament to an untimely death. Wolves or coyotes finished the easy victim of unintended trap off, and made off with the rest of the spoils. Found money for a wintering canine but a grisly and macabre ending for elk, deer or antelope.

I only noticed it happening where the crossing was more to ask of an ungulate than normal. They had no problem crossing one barbed wire fence. But three—or along a steep draw or on the crest of a hill—they couldn’t get enough speed or jump to clear, and would get hung up.

I refocused my attention back to Mike; he was right about it being a burial ground. Just several hundred yards above where we stood, on the top of the hill, with a commanding view of the entire lower Lemhi Valley, Chief Tendoy (Tin Doi), the last great Chief of the Lemhi Shoshoni, was buried up there in 1907. We both knew that more unmarked graves were scattered over that hill above, the result of a people placing their dead on that same hill for centuries beforehand.

He was very patiently waiting for my eye contact, and I finally complied. “Ghosts of my people,” he said, matter-of-factly. “My fathers are up there. It is a sacred burial ground. I cannot pass this point.”

I squished back down to him in the meltwater mud, to where he stood. “I’m sorry. I didn’t know.”

“It’s OK. I wouldn’t expect you to.” He grinned in a non-judgmental way. I think he was bemused that we white people would just brazenly step out there, unaware of what might befall us.

“Let’s go this way, Mike.” I led him down along the private land boundary, to a place where we could easily see the fences. I showed him where I had seen elk trapped in the wires. There were three fences, and a deep irrigation ditch, all within 50 yards total. We could see the worn travel paths where over 1000 of the big ungulates had crossed through the winter. Mike totally got it, and said that he’d get crews in to pull the fences down as soon as the ground thawed.

As we walked down the road back to his government truck, we talked about what else Caryl and I did besides ranching. “We run a contract business, doing vegetation measurement and monitoring. You know; noxious weed inventory, plant population mapping, timber measurement and volume estimation and some surveying. We’ve been working down in the Birch Creek Valley lately.”

We got to his truck, and he opened the door.

“In Birch Creek?” he said.

“Yes.” Birch Creek Valley is a 50 mile long valley to the about an hour south of where we stood. It was about 15 miles wide, and only had 1 ranch in it. It was the Nicholia Ranch, and they had a time of it over a long and difficult history. Word was that they had problems with lead poisoning in the water. Otherwise, the entire valley was uninhabited. There was a small town, Hahn, long since abandoned and now vanished with hardly a trace. There were more ranches and mines in it years ago, but they all went bankrupt. The climate was tough in the high country of Birch Creek. Frost happens 12 months a year. It might only rain 7 inches a year in the valley bottom. Then, in the winter, deep and drifting snows can blow the road shut for weeks at a time.

But it was a beautiful high mountain valley, ringed by some of the highest snow clad peaks in Idaho. Some of the best fly fishing I’ve experienced was in the crystal clear headwaters of the creek. They weren’t big rainbows, but they sure were voracious for my simple and clunky presentation of Adams dry flies. I’d fish beaver ponds for hours with a 1 year old Melanie on my back with a wary eye for the moose that had left their sign behind.

And Mike put his backpack in the truck, and turned back to face me. “Do you know about the Little People in Birch Creek? Have you seen them?”

“What are you talking about?”

“The Little People are—well—like a different race of humans. They are Indians, I think, but they are small—like 3 feet tall. They still live there, in Birch Creek. They are tricksters, and are very dangerous, because they are so crafty and mischievous. They have always lived there—for hundreds of years. It’s why no one else lives there. They have made sure of that. It is their land.”

I grinned. But on checking his eyes, I thought I’d better rethink. “Are you serious?”

“Oh yes.” Mike was serious. He had a slight grin to his face, mostly because he was seeing my expression, but I could tell he was not kidding. “So when I drive through the valley on Highway 28, I am careful not to look to the right or left. Because they will try to catch my eye as I pass through. And when they do, they may trap me with one of their tricks.” He wasn’t grinning anymore. “I know people that have gotten in trouble with them. And if they do catch you, well, they even might kill you.” He paused to let that sink in. “So it’s a little stressful driving through the valley on the way to Idaho Falls. You have to keep focused.” He paused and looked beyond me, going through it in his mind. “Yes…stay focused.” He turned to face me directly, looking me in the eye. “Be careful, working down there. My advice would be to get done with your job and never go back. They’ll take something from you; maybe even your life.”

With that, Mike jumped into his pickup. Pulling the door shut, he rolled down the window, and reached for my hand. “Glenn, it’s been a real pleasure visiting with you. Thanks again. We’ll take care of that fence.”

I watched him as he pulled away. The little people. I had actually heard something about them before; it was a theme that circulated through remote parts of the West. It seems many of these ancient and intact landscapes keep their folklore and their legends about them. Perhaps some of them are based in truth. We’ll likely never know. There are intriguing similar reports from other parts of the world (leprechauns, anyone?) and both the Crow and the Cherokee people have stories of the little people (the Crow call them “owners of the earth”). But stories have a way of dying with cultures, and despite efforts to do otherwise, the old stories and languages are fading away, just as how the windblown dust of the high desert has nearly erased the entire town site of Hahn from Birch Creek Valley.

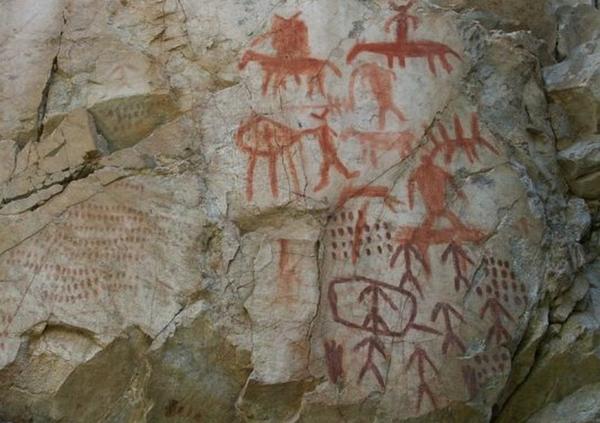

Caryl and I survived our work in Birch Creek with no ill effects from the Little People. It was a pretty unforgettable several months we worked up there. We camped up there with the kids, and saw no-one. It is a relatively untouched big valley, somewhat like Alaska in scale. The footprint of modern humanity had somehow not found this special place in a significant way; sure, there was evidence that people passed through, but almost nobody stayed. Yet, I knew that, despite its rugged climate, Native Americans endured there at least on a part time basis in spite of the Little People; perhaps they even coexisted. Ancestors of the Shoshoni at least lived there for some years. Numerous limestone outcroppings had caves or overhangs with remains of charcoal heaps in them; I’ve poked around in them, and found broken animal bones in them. People cooked and ate game there. The ceilings of grottos are black with centuries of smoke stains deposited from campfires. Cave paintings in red ocher adorn some of the walls. Archeologists have documented extensive evidence of significant populations of ancient Shoshoni that lived there.

On one of the last days we camped in the valley, several friends visited us in Birch Creek Camp. We climbed a high promontory that cropped out of the middle of the valley; it was an ancient lava flow. The ridge supported a small stand of conifer timber, unusual for the valley bottom. Drifting snow coming down the valley accumulated on the leeward side of the 200 foot tall ridge, and it was enough of a microclimate that trees could take hold on the basaltic outcrop. It was the only cover in the entire valley; the rest was open grassland and sagebrush, until you reached the higher elevations where trees were watered by mountain snowfall along the edges of snow covered peaks that vaunted up to 12000 feet. The basalt ridge is a unique break in an otherwise featureless valley floor.

There was a flat rock at the crest of the hill that offered a 100 mile view down Birch Creek into the distant Snake River Plain. As we sat down on the smooth black basalt, I realized that this view is also a 1000 year view. Little I could see was changed by the 20th century, and modern mankind, except the passage of highway 28 across the landscape below where we were seated.

Something caught the peripheral vision of one of my companions. It was Stephanie who spied a twinkle beneath the pine needle duff on the rock where we sat. She moved the debris around with her fingers, and discovered a perfect obsidian arrowhead. Picking it up, she handed it to me. I fingered the smooth and almost oily feeling glass that comprised the surface, and eyed the workmanship of the point maker. The edges were razor sharp, and the arrow tie notches perfect. Some Shoshoni craftsman had fashioned it at least a 150 years ago. In that time, the arrow and ties had rotted away, leaving only the point. It had to be at least that old since after that, manufactured points were well distributed by traders, and then, firearms.

Perhaps he was eyeing for buffalo; the telltale sign of dust rising to the sky would give them away, even over 50 miles. Maybe he was eyeing a small terrorizing band of Blackfeet coming up the valley. Regardless, he likely forgot his arrow there, as he too was captivated by the long view.

I resisted the inclination to put it in my pocket. And the others agreed with me. None of us could take it; I think we all knew that it was part of the story of the landscape; like the cave paintings, it told a tale of a lost civilization. Perhaps even one of the Little People had left it there, if indeed they existed. We placed it back on the flat rock where we found it, leaving it for another wayfarer to come upon. Maybe it would be rediscovered in another 1000 years. And, in retrospect, I think we were not too unlike Mike. I don’t think any of us saw this ground as sacred, but we did share a respect for it because it bore an intrigue for the mystery of those who were here before.

It’s the same way we view the open and wild lands we graze, just 80 miles from Birch Creek, in the next valley, this Pahsimeroi. I’m coaching some of my new crew members, even now, during the hiring process. I’m seeing if our new employees can capture our vision. I’ve already told them about stewardship and husbandry of these wild landscapes; in leaving the land better than when we came. It’s because there’s wonder in discovery of the pristine. We should all have a right to explore and uncover. And it’s our duty to keep these special gifts of wild and pristine intact, so my grandchildren and their children can discover the stories and unravel the mysteries the landscape has to offer on another day.

Happy Trails.

“‹”‹”‹”‹”‹”‹”‹Glenn, Caryl, daughters and cowboys

Leave a Reply