Despite the earth-moving events that would unfold later in the afternoon, this particular August day dawned like any other over the Hat Creek country. It was 1959, and the only witness to the devastation was one Dick McDaniel, who tended his sheep in the lower breaks of the range along the Salmon River. Dick shepherded his sheep up in the lower country; his grazing lands were in the steep hills and canyons that broke into the Salmon River.

It was a peaceful morning that day, with clear blue skies. It was going to be hot, though, and that meant it was likely that there would be thunderstorms in the mountains that afternoon. Huge cumulonimbus clouds would coalesce as the hot, humid air rising over the baking pan of the Eastern Oregon desert collided with the high mountain ranges of central Idaho.

Millions of gallons of moisture would condense in towering clouds that sported trailing “anvil” heads that reached up to 50,000 feet where cloud mist froze in the frigid air. The towering white monoliths came charged with static electricity and fairly glowed with continuous lightning that ignited within. And they could dump their floating ocean of water anytime, anywhere. Today, it would be over Hat Creek, and nearly a half-century of cattle grazing had left its landscape raw and vulnerable.

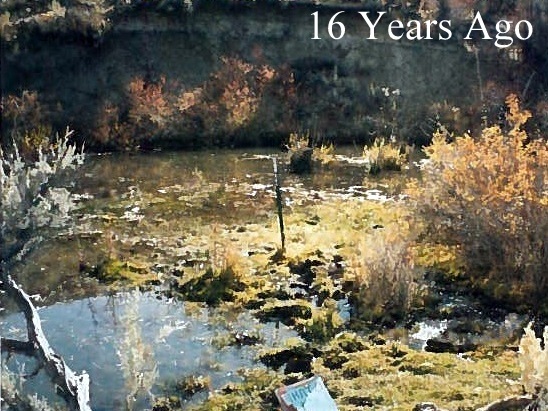

Upwards of 3500 head grazed through Hat Creek each year. It seemed the grass would never end, and hungry cattle brought in by money hungry cowboys gobbled up the resilient forage year after year. The trend of change was nearly imperceptible despite the degradation that was occurring. After all, the grass was always there, as was the sagebrush, fir trees, and aspen. It always grew back. But only an investment of data gathering in plant monitoring or photographs could have documented the change.

The human mind is malleable, and would not register a trend of change like the black and white of a photo could. But no-one in those days had the foresight, the vision to desire such a capture of information. Instead, they saw the unending and renewable resource of grass in a post-war America where optimism and conquest without consequence had reached new levels.

If they had measured, photographed or in some way documented the trend of vegetation on not only Hat Creek, but all the ranges of the American West, they would have seen what their eyes couldn’t see: the land had been stripped of resilience not necessarily to grazing, but to flood.

It was what was absent underground that created the unprecedented vulnerability in the landscape. The continuous grazing had weakened the centuries-old matrix of roots of grasses and sagebrush on the uplands, and sedges, rushes, grasses and willows along the streamside. With year after year of unrelenting grazing pressure, the plants thinned and died leaving soil exposed, and the living root matrix thinned as well.

Sure, the bison had lived here for millennia, but their visits were sporadic and often in high densities for short duration. Bison would visit a creek bottom perhaps once every 10 or 20 years. Their use stimulated new growth and prevented stagnation of plant communities because it wasn’t continuous.

The stage was set. One particularly stupendously huge storm cell settled over Hat Creek. The sun was blotted out; a cold wind from high within the tumultuous column of cloud blew down from 40,000 feet. And with the wind came the first thick drops of rain. Dick’s sheep paced nervously as the first drops fell, and the low rumble of thunder rattled the ground beneath their feet.

They were big drops, and packed a lot of impact to the stripped-bare soil. The cows had already come and gone through the low country, and the grass wouldn’t grow back until next spring. Exposed soils were the norm this day in Hat Creek, and with each drop of rain, soil was disturbed.

Directly, the drops became a downpour. Raindrops became muddy trickles on the exposed ground; trickles became rivulets, rivulets became streams, streams became raging torrents of thick mud. When torrents joined in canyon and creek bottom, they became a flash flood of mud, rock and debris that tore at the vulnerable shrubless and treeless banks of the overgrazed creeks.

I learned about the deluge from Dick McDaniel, when I was helping him out on his Salmon River ranch with his cattle. I asked him what carved out Pig Creek; it had quite a canyon to it; it was even hard to get a horse down and across the creek.

“Pig Creek was the worst of it,” Dick told me. “That water just tore a whole new canyon out and put all that material in Little Hat Creek, where it finally flatted and spread out. All of that downcutting you see in all these low creeks was from that one event in 1959.” He looked beyond me and his Salmon River ranch into the hills beyond. He was remembering. “It was the worst thunderstorm flood I had ever seen.”

Canyons were cut in the exposed volcanic soils. Rock the size of washing machines rolled for miles downstream. The mud torrent eventually dumped into the Salmon River, almost damming it. Sheer banks of soil over 20 feet lay bare. Floodplain moist meadow plant communities along creeks that had somehow survived the grazing regime now had their fate sealed. The down-cut creek and water table now lay 20 feet below their roots. The moisture-loving plants dried and died.

As you likely figured out, dear reader, the 70 square miles of rangeland landscape that I call Hat Creek is where we are summer grazing Alderspring’s cattle. And the lessons of a raw landscape, combined with 12,000 trend photographs that we have taken up there and reams of monitoring data have taught us the lessons that we needed to learn to restore and recover what was lost.

The good news is that wetland and creekside systems, even in our high desert environment are very resilient. Endangered bull trout are recolonizing our 55 miles of creeks. Birds are returning to abundant tree nesting habitat. How does this happen?

First of all, we don’t graze 3500 head up there. We only graze around 300. But even that small amount can stop restoration, if cattle are left on their own. And that was the key that unlocked the door to full on recovery. We needed to stop leaving them to their own devices.

You see, with the advent of barbed wire, cowboys stopped living on the range with their cattle. They let the cows manage themselves, and the cowboys simply gathered them in the fall. Cows can tend to get lazy and cultivate an entitlement attitude if allowed to do so, and will spend their entire life living off the fat of the land found in wetlands and creeks, and overwhelm such fragile habitats with their sheer volume and size. Bison, on the other hand, were trained quite well by grizzlies, lions and wolves to not use the dense cover in creeks (the fierce predators would lie in wait for them there—they could get lazy too). So bison kept a move on, and traveled extensively, herded by predators.

So we took a lesson from the bison, predators and the cowboys of old. What if we lived with our cattle, and mimicked the bison/predator interaction by herding our beeves actively across the landscape?

The concept of inherding was born. We call it that because we herd the cattle “in” where we want them to be instead of “out” of where we don’t want them to be, a new type of restoration ranching. Before, we would find wayward cows in creeks and other sensitive areas, and we would herd them out. But we had 300 cows up there on the range, and they were everywhere, scattered over 70 square miles. There would always be ones we missed that were causing some kind of habitat issue. They simply didn’t have the trained instinct that the bison did.

So instead of 65% of our 55 miles of creeks having some sort of alteration by our wayward cows, we now have less than 2% of those miles affected by our herded cows; those are planned areas that we bring the cattle to for watering; areas that we selected beforehand that were “armored” by down logs or rocks so we don’t disturb the fragile streambank ecosystem.

Inherding, in a word, is proactive management of these sensitive systems instead of reactive. We plan where to graze. Now you might say, why even bother? Why not just leave the wild range alone? It’s a good point. But here’s the other side of it: the wilderness of the wild rangelands offers our beeves some of the most nutrient dense forage in the world. We create flavor in beef that indicates a great wellness opportunity. And with careful stewardship, it is an agricultural system that is truly sustainable. It’s this huge untapped resource in this world where most grass fed beef is raised on farmland that has been plowed, ripped, sprayed and fertilized for over 100 years.

But this—it’s a land that’s never been plowed or farmed. It has always been wilderness. And the volcanic soils have not been altered, except where erosion from too many cows changed it with an event like that in 1959.

Those woody and grass species are nearly back to prehistoric levels now, after only 12 years in our care. And inherding is the next level of proactive stewardship. It even has provided for us a key to coexist with wolves—a missing part of the ecosystem since they were exterminated by aggressive cattlemen and sheepmen by 1950. Now, they are back, and recovered, and they were eating our cows. They liked grass fed beef, probably for the same reasons you do.

But they do not trust humans, as no predator in nature trusts another top of the food chain predator. And as a result, since we live with our cattle 24/7, just our presence on the land has been successful in keeping wolves at bay, in a non-lethal relationship, for both parties involved.

So inherding is a win/win situation. We can continue our restoration of these native and wild rangelands while raising the best protein we can imagine. And all other residents that we share the landscape with from bull trout to black bears thrive again. And hopefully, thanks to your continued partnership in our endeavors, if the 1959 supercell opens its floodgates over Hat Creek again, wild plant roots will prevail, and soil integrity will stand. It’s our greatest hope.

Thanks for standing with us. For roots and wild soils that are the foundation for the best beef, while allowing fish and wildlife to absolutely thrive.

Leave a Reply