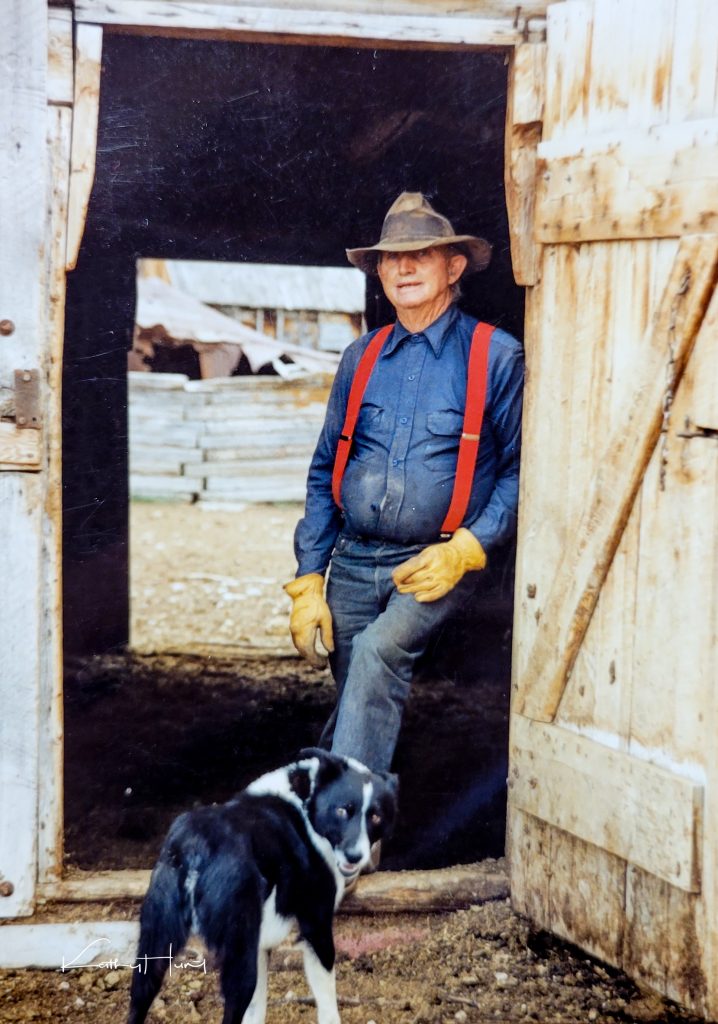

Photos in this story were taken by Kathy Hunt. Currently based in Arizona, she still is passionate about telling the story of ranching in the West through her pictures. You can see more of her wonderful images on her Facebook page Here.

Dear Friends

“It’s gone,” Caryl plainly stated as she stared out of the 65 mile-an-hour Yukon window yesterday.

I knew what she was looking for, even though we had never talked about it. I, too, took my eyes from the road and scanned the distant spread of fields—flat hay meadows stretching for a mile or two on the west side of state highway 28 that abruptly terminated at the sudden and almost violent rise of the Lemhi Mountain Range.

She was right: we were driving by the old Clark Ranch and the 30-foot-tall wooden edifice of the ‘beaverslide’ hay stacker was gone. Something nudged me below the ribcage. It wasn’t pain; more like heartache. Somehow you think that these monuments to our memories will just stand there forever, and always pull the trigger for you, bringing back a rush of remembrance to when things were simple and beautiful.

But then, someone unwittingly takes down that which gives you joyful memory. They pull them to the ground with a chain hooked to pickup or tractor and the now-obsolete labor of love is cut into pieces for firewood. They’re completely ignorant of the importance to passers-by. I’ve seen it often; an old log cabin collapses, and someone sets it on fire. And in a few days, I’ll be in the line at the grocery store, and they’ll mention it to me. “That was my grandad’s place,” they’ll quietly say. “My mama was born there.”

I look, and their eyes are wet.

The Clark outfit straddled the serpentine flow of Tex Creek, a crystal-clear convergence of springwater that emanates from the base of snow-bound cirques of the high quartzite peaks. It is one of the last, the highest ranches in the narrow plain before flats tilt up to meet destiny in the rugged timber and rocks of the snow-capped Lemhi and Beaverhead mountain ranges.

The ranch changed hands after Lloyd passed, now decades ago. He and his wife, Beva were the vision, the backbone, the muscle, the persevering and persistent forces that never gave up on that place when everyone else would have. They took over the ranch in 1946 and never left: survivors.

I think it was summers that kept them there. If one could just endure the springtime rush of mosquitoes, grass grew with an incredible abandon at this 7000-foot elevation (leaves of grass cared not about the bloodsucking menaces). Temperatures would occasionally soar into the 90s under that high-altitude sun. If I didn’t bring a hat, my ears would become barbeque in one afternoon of exposure (Lloyd would laugh). But then, that unrelenting seeming sun would slip behind the peaks. Light would continue for hours thanks to the higher latitude. Darkness would finally settle in at around 10:30 pm.

And then, in just a half an hour, I’d suddenly be reminded that winter was just around the corner. By midnight, temps could plummet to the low 40s under a diamond sparkling raiment of a million-star sky. And while laying down under thick blankets with ears smarting afire from the sun’s toasting, I knew that the urgency of a short season was real.

My thinking is that even the grasses and sedges knew that they had to hurry—that’s why they could be so productive. They didn’t have much time in a place where snow fell at every month of the year, and “frost-free” was measured in days–not weeks.

“The grass here is hard,” Lloyd used to tell me. He meant that it was more powerful—concentrated than the long-growing season stuff in the low country. And now in retrospect, I believe he was right. And so, he would gather the summer excess of grass—more than the cows could eat during the green season–in hay. Like the wild plants and animals he shared the austere mountain-walled landscape with, he knew he would desperately need it in the offseason to keep his livestock alive.

Lloyd raised sheep, cattle, horses, daughters and sons on that hard grass. They never made much money, but more often than not, had enough. But it was a margin-less existence. When the kids grew up, they intuitively moved elsewhere, still keeping touch with Lloyd and Beva, who continued on the land ““ persistent, still optimistic with the hope that next year would be better.

It was the summer of 1991, and I had been working for Lloyd and Beva on and off for several weekends after the snow came off. Hay season was coming, and Lloyd’s focus was getting the equipment ready. The equipment was simple and was nearly all horse-drawn. Lloyd was by no means Amish; he simply chose horse and mule over gas and diesel. He lived on horseback and behind horse; those he enjoyed and understood. Engines he did not. We sharpened sickle-bars by hand, checked grease and gearbox oil (drained water). But there was one project that particular year that commanded attention: the Beaverslide.

Lloyd simply called it “the derrick.” Last year’s model was absolutely shot but was still standing. It was a 30-foot-tall triangular contraption made of wood, cables and pulleys. The purpose: to literally throw big piles of cured grass up through the air to the top of a growing haystack that may be as high as 20 feet tall. The haystack would preserve the green cure in a fairly airtight vertically concentrated pile, and the topmost stems would act as a sort of thatched roof from the rain and snow elements that can otherwise rot a smaller stack.

No one I’ve met knows exactly why it’s often called a Beaverslide. Maybe because the origin seems to be around the area of the Beaverhead mountains, that range that spans the Idaho and Montana border. It certainly was the most prevalent area of their use. Some say it is named that after the slides that beavers have along their dam-works along creeks. Otters have much better ones, but somehow ‘otterslide’ doesn’t seem to fit. The sliding part of the title is indeed fitting, as even humans can take the ‘slide-ride’ up (quite fun, I have to say—but keep those arms and hands tucked in!).

In any case, the slide, or derrick was rather ingenious. As Caryl and I learned to operate it singlehandedly, I think that word would transform to elegant. I say singlehandedly, but it wasn’t really the case. There were two others that helped us stack those years we worked for Lloyd; one was named Roanie and the other, Nod.

Roanie was a giant near geriatric Belgian draft gelding with feet the size of dinner plates. Nod was a half draft jet black mule, also aged, but very alert. His large ears would twist and screw in our direction when we spoke their names from the top of the stack when a load of hay was ready to lift. And they would obediently lean into their traces, which would tighten their tug chains, which would straighten and strain their double trees to vibrating with tension and potential.

Double trees were connected by a clevis ring to a cable that ran through a series of pulleys that lifted the great load of accumulated hay off the ground, all driven by literal horsepower. The burden would lift with the transfer of the power from the team’s forward motion through the pulleys to the hay-carrier, which carried it up the slide and dumped it at the top. A quick word of “Giddup!” or “Roanie, Nod!”, would shoot the hay further out across the broad top of the stack, facilitating an easy job of the final leveling of the pile of hay with pitchfork by the person perched on top of the stack .

The derrick had to go through repeated motions the upcoming season, it had to bear incredible amounts of weight, tension and torque. On inspection of the old beaverslide with Lloyd, it was immediately apparent that it would never do. The decades and the elements had taken a toll on the wooden construction, the legacy of raw and snowy winter seasons and hot high-altitude sun. It was still parked at the last stack of the previous year (there were many stackyards, as the derrick was mobile, dragged on skids from field to field by a team of 4 horses and mules). The great upright timbers were completely rotten, as were the 16-inch diameter skids underneath.

Lloyd was rightly concerned that the entire structure could dangerously implode under the first strain and pressure of movement—or hay stacking. His gravelly voice murmured something along the lines of “she ain’t a gonna hold up for another year” as if past personal experience with such self-destructive forces etched deep scars into his memory (they probably did).

So Lloyd set to work, directing me where to cut (he soon happily figured out that I could run a chainsaw) and lift (young and strong back, weak mind) and drill holes (with hand-powered and Egyptian pyramid era invention of ‘brace and bit). He found me a good double bit axe with which I was fairly adept. I followed Lloyd to his dark-shadowed and well stocked but very cluttered shop with a single light bulb and cracks in the wall boards dimly showing the way to an ancient pedal-powered stone sharpening wheel.

Lloyd, wisely considering the future of the next season, located some very long lodgepole pines deep in the thick forests up on Leadore Hill, behind the ranch, and skidded them out over deep snow with his teams of horses in the quiet frigidity of January, five months previous to our mosquitoed morning and heating up June sun-days. I imagined him alone up there in the timber and deep snow, wool pants dusted with frozen powder. His grizzled and 73-year-old mug eyeing tall timber, thinking of hay to cut on a subzero afternoon of all things ““ horses harnessed, breathing deeply, moist hides steaming from the climb up with Lloyd behind, holding thick leather lines.

Back to the summer: we pried and pulled iron, pulley and cable from the old derrick, now becoming firewood for the wood stove next winter, forging, welding where necessary to make the iron and steel hardware submit to the task of a new derrick. The parts originated from local forges and ironsmiths down valley, in Salmon, Idaho or Dillon Montana, perhaps, long ago ““ even a hundred years prior. At that time, the beaverslide was the high point of a new technology that paired horse and human to accomplish new heights in haymaking. John Deere, with his ubiquitous country-wide cropping solutions had little to say on this provincial haymaking innovation. It would only prove to work well in the high desert powder-dry air of the intermountain west. Here, the hay alone protected that stack with its own thatched roof. Anywhere else, subjected to frequent rain and wet snow in a more-moist clime, hay would have to be barned or shedded.

Over the next few weeks, the derrick took shape. I worked with him on the wood and steel resurrection, as did many others. There were friends, neighbors, grandkids, sons and daughters. It was how the work of hay harvest always happened on the Clark Ranch. There was no plan. People simply just showed up. It literally took a village, and it was one that Lloyd and Beva had unintentionally built by opening their doors wide for anyone that came down their long Tex Creek lane. Sometimes, people didn’t even know why they came. Lloyd and Beva would literally give them a seat at the table and put them to work. If the Clarks were still ranching today, you would be welcome too.

I had absolutely no clear idea how in the world Lloyd was conceptualizing the final stage. We had pieces, the two sides, far too heavy to lift, even by a cadre of willing humans. How would we even begin to stand the timbers up? I would ask him, and he would only say “Oh, we’ll get it, honey. Don’t worry.” (He called all of us who helped him “Honey.” Age and gender meant nothing to him).

Finally, the pieces were ready. I got there early that day, still wondering what or how Lloyd had planned to raise derrick from the dead. The sun was just breaking the horizon over the high Beaverhead Mountains when I pulled up. Lloyd called me in from behind the wood-weathered screen door for the usual pancakes fried half submerged in bacon fat on the wood cook stove, left over from the thick bacon already plated on the table by his longtime bride Beva (a.k.a., the “Cook,” during the hay days).

I squinted into the rising sun, looking over at the field next to the shop, where derrick lay in pieces waiting for assembly. I almost gasped. There was something there ““ a sort of reverse anachronism. It was unmistakably a boom truck—a portable crane. I looked back at Lloyd, where he had stood at the screened threshold to his graying sun-bronzed and aging cracked log cabin. He had already headed in. A remembrance of words often uttered came to mind: “Never keep the Cook waiting.”

The sun was already high when we got to the unassembled derrick and boom truck. Mosquitoes were fairly teeming. Looking over at Lloyd, his head was in a cloud of them. Noticing the long gray whiskers cropped up between leathery fissures on his face, I realized why he didn’t mind them. And why he put up with greenhorns like me. It was simple: if I were given the choice between an old saggy-skinned pin bone poking, rib rearing, dried leather skinned bull and a plump, fat young steer to gnaw on a ribeye from, the latter was the clear choice. My face was baby flesh compared to Lloyd’s. I slapped a palm to my cheek. Three blood-smeared carcasses in one hit. Lloyd was watching in a sidelong sort of way. And a semblance of a grin creased his furrowed face.

“You run it, Honey.” Lloyd slowly winked. He hated petroleum powered machines of all kinds, and absolutely relished unleashing my meager mechanical abilities. On these ancient museum relics, my skills were generally enough. Points. Timing. Dwell. Spark. Fuel. It was all it took to make internal combustion fire.

And the crane roared to life. It was Larry’s, Lloyd’s son. Larry had driven it up from his home in Rigby, Idaho, nearly two hours away. The boom slowly extended under the rough control levers. It was slow, but it would certainly do. Lloyd smiled at the prospect of connecting timber to timber, with massive bolts forged a century ago. No new bolts on this project. It was 1988, and we were state of the art—one hundred years ago.

I reflected on the why of that. A year before, I needed some nails on a project for Lloyd. We were piecing together a wagon deck. Not a wholesale replacement, mind you. We were only mending missing boards. They became puzzle pieces that we made with saw and chisel.

I dove into the darkened shop to find nails, Lloyd slowly making his way behind me (at this point in life, hurry wasn’t something he cared about). The workbench in said shop was invisible due to the pile of tools, parts, bolts and random iron fasteners on the deck. I began rifling through the bottomless heap for a handful of nails. And then, in a shaft of sunlight sent downward from the porous roof, I saw it, on the shelf below the bench.

It was a brand new full wooden keg of nails, probably, by the looks of it, 40 years old. Never even opened. I knew it because it said so: 16 Penny common. 50 lbs. Eureka! I reached down to open the holy nail grail, and found the heavenly light extinguished by the shadow of Lloyd. I slowly looked up when I felt him looking at me.

“Honey. You don’t have to open that keg. I got these right here.” He looked down into his cupped hand, and my eyes followed his. There were about 30 random nails, rusted, mismatched, and mostly bent. He looked up at me. “It’ll only take a few minutes at the anvil to straighten these.” His grin showed worn teeth, gold and silver with filling. And then: “We might need them other ones someday.”

Speechless would have been the word most appropriate to describe my would-be words; I had none. And so, I straightened nails for a half hour or so. And dutifully drove them home into puzzle piece wagon bed. Since then, I’ve witnessed several other depression era survivors just like Lloyd. That time. The worst hard time. Those that somehow made it learned how to save it. Not just one thing. Every-thing. And they still held on to what they could in case it happened again.

Slowly, over days, the derrick took vertical shape. Great rusted bolts once again held the big logs fast and firm. Rusted and worn cables yet another time ran through the squeaking pulleys. We built the hay rack, a multitudinous matrix of lodgepole pine teeth that would come to life under the power and pull of quivering horseflesh and lift masses of hay against gravity skyward. We nailed (with straightened and re-used rusting spikes) the steel runways that, like railroad tracks, would carry the weight of the hay rack upward.

Nearing the end of a long day, we finished. The peeling and weather-worn logs of the high upright framework were illuminated with a bronze tint in the setting alpenglow sun. It was a monument, a gleaming testament to the power of horse and human ingenuity. Passing vehicles on highway 28, two miles away, would be able to pick it out.

“Are we gonna try it?”, I eagerly asked Lloyd.

“Tomorrow’s another day, Honey.” His face, like the weathered wood, shone bronze too. He cracked a grin and winked his trademark slow tip of an eyelid. “Besides,” his eyes drifted down to the blackened leather lariat tied to his pocket watch as he hauled it out of his graying and worn smooth Levi’s, “The Cook’s ready.”

The derrick worked like a well-oiled machine over the next summers. Sure, cables needed adjusting; pulleys needed a brush of axle grease. The rail-runners up the sides would shine in the high summer sun with a reflecting polish as one pass after another of hay would ride aloft to the summit of stack.

I never tired of watching it work. I don’t even know exactly why. There was a simple beauty to it all. Horse and human working together on the wonder of a well-built stack. Summer sunshine would be encapsulated in the great hay-pile, to be cracked open when Arctic winter winds would pour down from the high Canadian North along the Rocky Mountain Front. Cattle and sheep would wait for it, knowing and trusting we would deliver. There was a circle of beauty there in the harvest and presentation of grass and graze through the seasons. I will never forget it.

And that derrick—that Beaverslide, was the last of its kind. Nowhere else in my travels and forays through the high West have I seen one again in operation, let alone be built. The use of Lloyd’s marks the end of an era, before smartphones, smart cars and smart homes.

After several years of running that derrick, Lloyd passed away. Just before that, he had some heart issues, and we ventured up to the high valley to visit. We were busy then. We had started our own family and our own ranch, but knew we didn’t have much time left. Lloyd got to hold a perfectly formed smooth soft-skinned few-months old Melanie in his wrinkled and leather cracked hands on his lap before he faded away not long after.

She so wishes that she could have known him. I don’t know how, but some of that same Clark stubbornness shows up in my kids. Perhaps it’s what we, as parents learned from the likes of Lloyd and Beva. I told Melanie that he would have called her “Honey.” And she liked it.

Oh—and one more thing: to my knowledge, he never did open that keg of nails. Thank God he never needed them.

Happy Trails.

Kitty Ward

Thanks, for your story and photos😉

Your article was packed with wonderful tales of the past…

Happy Trails to all,

Kitty

Circa 1949

Caryl Elzinga

Thanks so much Kitty! It was great to share the journey to the past!

-Glenn

Kate Miller

From generation to generation – as always your writing is like a detailed painting one can just step right into – enjoy it so much! Thanks

skyler Epperson

Its the hard grass that makes that toughness pass down.