This week’s story is from Abigail Kelly, our daughter, about growing up on the first Alderspring Ranch. Abby and her husband Ethan grow our pastured pork that’s in the webstore, and Abby is the current herdswoman for all of our home ranch cow calf pairs. The story that follows takes place about 25 years ago on the first Alderspring where all 7 daughters were born. The older ones learned how to ride on that ranch, and grew as the herd grew and expanded. Early Alderspring was a hardscrabble existence; we had spent all we had on cattle, land, horses and equipment, and everything was on the cheap. Housing was pretty rough, old, drafty and leaky, but we were happy and warm. We always had plenty to eat between elk, venison, beef and huge gardens where we gathered scores of canning jars of food for the winter. When I ask the kids about it, they always remember the good things. And that’s the way it should be. But there were a few times they remembered when it was hard–especially when I asked them to do the horseback work that even most adults wouldn’t possibly be able to handle. Sometimes we talk about it, and I have regrets. But they have none. In fact, they’ll thank me for those times. This is one of those…

Sometimes my older sister Melanie and I talk about why we have trust issues with Dad. Even though we’re adults now, he’ll still try to put one over on us. Then again, maybe we’re to blame. We’re pretty gullible.

I’m sitting here right now watching a gentle fall breeze toss the leaves of my Siouxland poplars. My husband and I planted them beside this old house. Ethan and I have been married three years, and sometimes we feel like pioneers on this rock pile, trying to scratch a home, a living, out of the dirt.

Thankfully, the baby is asleep upstairs. She’s six months old and almost crawling. You might say the trees are more for her than for us, although by the time we are old we’ll have some nice shade to sit under.

My family hasn’t always lived here in the Pahsimeroi. When I was little, we lived on the other side of the mountain range to the northeast, in the Lemhi Valley. That was the ranch where I really grew up, but the valley became small, and tight with other people. The Pahsimeroi has given us room to grow, to plant trees.

As always, autumn is bittersweet. The leafy vegetables in our gardens turn black, first the zucchini and then the squash. Snow covers the mountains. We begin to think about the cold, stacking our firewood and canning everything we can. We pick up anything in our yards that we don’t want frozen to the ground. We blanket our roses in straw and beg them to come back next year. To me, fall has always been an ending. It signifies time passing by. This fall weather reminds me of other years, and this breeze, flickering the leaves of my poplars, carries me back, over the mountains, to another fall.

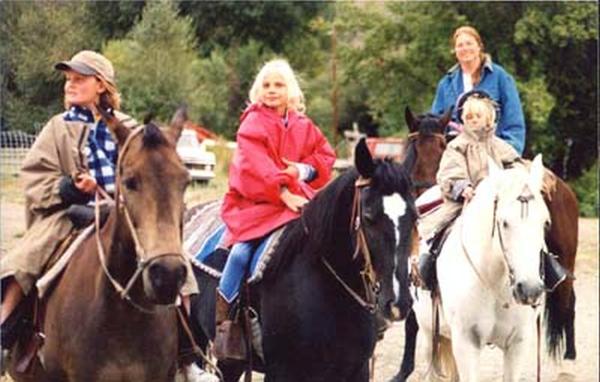

Dad didn’t have anyone besides us in those days. There were the two of us, Melanie and I. She was probably eight and I was not more than six. It was a matter of pride in the little girl competition with our friends that we had been riding since we were five.

We had three horses then. If Dad had known they would gradually turn into thirty, the first three would have been hard to talk him into.

He had Missy. She was a short-backed, blood bay Morgan with a work ethic. She regarded small children and women with scorn. She swung her feet out when she walked, and her trot was more of a prance. She was a proud, proud horse. Years later, when we were teenagers and thought we knew some things about horsemanship, we tried to put a bit in her mouth, and were met once again with her scorn. Missy never worked in anything but the bitless hackamore.

After Missy there was Gus. Gus was a golden buckskin with the huge hip that quarter horse lovers have come to admire. He had a black dorsal stripe running the length of his back, and dark socks around his legs. He had a star. Later in life, Gus’s huge hips would make him slightly pigeon-toed. His bright, wide chest would diminish. His muzzle would become less black and more gray. The spirited eyes would grow dull. We put him with the other geriatrics, and let him live out his life in retirement for a few more years, but I’ll always remember him as he was in his prime: tall, thick, and as bright as a new penny.

In addition to Gus and Missy, who were purchased together, there was Bonny. No one ever knew how old she really was. It was a matter understood among us that she had one day, long, long ago been black. But, as many people will tell you, a white horse often starts off black, which fades to gray and then white. Bonny, as I knew her, was always white.

She was a wild mustang wrangled in from the herds that ran in the big country up above Challis, Idaho in the next valley, and though her conformation would have impressed neither the American Quarter Horse Association or the Morgan Horse Association, her feet were hard and black and never needed shoes. Mustangs were that way. If their feet fell apart on the broken range country, they simply fell behind the herd and died. With them went their bad-footed bloodlines. Nature was merciless when it came to sorting the fit from the failing.

We bought Bonny from some friends of ours when they moved away to Alaska. Where Missy was proud, and Gus was handsome, she was kind.

As I think of her now, I picture her sleeping, head slightly bowed, back foot cocked, her white eyelashes fluttering, her gray lower lip twitching just a little to keep the flies off of it.

She was the the very first horse for all of us. Her kindness gave grace to the roughshod way little kids could be with a horse. She’d put up with anything. I remember we dressed her as a unicorn once, and 5 of us little girls donned princess dresses and all 5 of us rode astride her broad swayed back.

I remember one of those cold nights, when fall comes creeping down from the mountains, and colors the cottonwoods and aspens gold. It was just early enough in the fall that we didn’t bring gloves along, but far enough along that our fingers were frozen and stiff by the end of the ride.

I remember it as a long day, one of the longest. We’d brought some cattle from far out on what we called “Craigs” a piece of rental property adjacent to our ranch. In those days, Craigs seemed to be an infinite expanse of land, when in reality it could not have been more than a few miles. Now, when I go back to the old ranch, the ranch where I grew up, it saddens me to see how small it is, compared to how big I remember it. I don’t go back there very often.

Being only six, it was a real chore to get aboard a horse in the first place. First there was the whole matter of getting the saddle and blanket on, which for a six year old could be compared to sending the first astronaut to the moon. Then there was the cinching up, which took an incredible amount of leverage, especially on Bonny, who tended to fill her stomach with air just as I was beginning the cinching. After the cinch was tight, there was the special knot to remember which my hands know to this day. I can more easily do it than teach it, so second nature has it now become. There was a right way to the knot and a wrong way.

Melanie has always done it “wrong”. She’s left-handed. As far as I know, she still does it that way, even though she is an accomplished horsewoman and trainer.

After the cinch is tied and ready, there’s the bridling to consider. Gus had a bad habit of throwing his head up in the air, out of the reach of eight-year olds. Melanie and I shed a great many tears over it.

Once we were aboard, there was the problem of staying that way. When we had first gotten Gus and Missy, Dad took us for a ride. Melanie I were riding double on Gus. I was on the back, being the youngest. We were going along all right following Dad, when he suddenly decided to try out Missy’s trot.

Now, Missy had a very nice, smooth trot. You could ride her trot for hours. But Gus, being a typical Quarter horse, had a trot like a catapult. When Gus saw Missy trotting, he decided he’d like to keep up with her. We didn’t last that long. It was only a few seconds before we were together on the ground, and Gus was leaving without us.

Although there was a good deal of crying, we weren’t actually hurt. Dad came riding back to us. I think he was laughing. He told us to get back on.

So there we were, just coming back from a long cattle drive on Craigs. The night was moonless, but I remember stars coming out in the dusk, and the vague shadows of the mountains and trees against the blue-black sky. Somewhere down along Agency Creek, in the cottonwoods, a Great Horned owl made himself known.

Dad got off Missy and left her ground-tied as he went to shut the gate behind the cattle we just brought in to the home place. There was a cold breeze, just enough to freeze our cheeks. My short legs were cramped from doing the splits across Bonny’s broad Mustang back all afternoon. I couldn’t really feel my toes.

Gus gave a sigh, like a tired horse does at the end of the day. “It’s so cold.” Melanie whimpered, hunching her shoulders like a turtle, and looking eagerly toward the lights of the house. We had been doing the “Rein Swap” for the last hour, where you hold your reins with one hand and put the other in your coat, then swap hands.

We could hear the barbed wire squeak as Dad finished shutting the gate, then he walked over to stand next to us.

“Well, you guys,” he said, leaning up against Gus’s shoulder and looking at each of us in turn. The look made us uneasy. “We’re almost done.”

There were coyotes howling up on the bar. Short little yips, then high pitched howls. You could hear which ones were the young ones (they weren’t very good at being coyotes yet). Bamer, Dad’s mutt dog, growled softly in their direction.

Dad gathered Missy’s reins off the ground, “There’s just one more pair out on Craigs that we need to go get.”

Melanie and I both looked at him in despair. We both thought of the long, dark road that twisted through currant bushes, then climbed the hill to the bar. Then the expanse of waving grass, two ditch crossings of murky cold water, and two tangled gates. It was a long way back to Craigs. We started to cry, the kind of husky, tired cry that six and eight-year-olds do when they have been looking forward to going inside for a long time.

Dad mounted up, and our crying turned to silence as we cast pleading eyes in his direction. He didn’t seem to pay any attention. Instead, he turned Missy around and started riding away. But he was riding the wrong way. He wasn’t heading toward Craigs, he was heading back to the house. Were we supposed to get the pair alone? In this cold night?

“Dad?” Melanie called, a note of panic in her voice. Her head had all but disappeared into her coat collar. Missy’s foot clattered on a rock and Gus and Bonny started to tug on their reins. They wanted to go home, too.

“Just kidding!” Dad shouted back to us, as Missy broke into an eager trot, “Come on!”

I would like to say that we’ve learned our lesson, that we know now what is a joke and what’s for real. I’d like to tell you I have studied his body language, the subtle cues of eye contact and blinking, and that I know enough to not ever be fooled again.

But that’s not the case. Then again, I’m only 22. He still calls us kids. Perhaps I just need more practice.

David Jensen

The life stories you all post are very well told and inspiring! Thanks, Hope to ride and work along side of your family one day!

David Wagner

😊🇺🇸

Pam

I love this story! Thank you for sharing it.