After the ground crew pulled wheel chocks, Howard Thompson, Flight Officer aboard the B-17 Flying Fortress fired up the 4 Pratt and Whitney engines while Commanding Officer and First Lieutenant Joe Brensinger worked through the preflight. It was late Tuesday afternoon, on March 30, 1943. It wasn’t their first training mission, by any means; this one focused on local navigation skills. As they prepared for takeoff, all of the 9 young men on board knew very well their ultimate fate once their training was completed: it would most likely be over the skies of Germany, dropping bombs on Axis targets. It would happen soon enough; there was no imminent path toward victory in either the Europe or Pacific theaters.

As the Fortress taxied to the runway, an ominous and brisk northwest wind blew across the tarmac in Walla Walla, Washington. Gray moisture bearing clouds coalesced over the airfield. The electric heaters had not yet actuated in their flight suits, and Joe could feel the cold in his bones. An Alabama boy, he had to rapidly adapt to the weather of Walla Walla. Despite the semi-arid environment in the rain shadow of the Cascades, northern winds would combine with Pacific moisture flow and occasionally dump wet snow and cold across this portion of Washington. It was a far cry from the persistent green warmth of his home town of Fairfield, smack dab in the middle of ‘Bama.

In just several hours, Joe would have endure to a far more wintery fate. At the end, he would survive, but the perils of frostbite and exposure would bring him to the brink of death sooner than gunfire from a German Messerschmitt fighter aircraft.

The aircraft gained altitude over the timbered waves of the Blue Mountains in Oregon and leveled out at a cruising altitude of 20,000 feet. The crew was entirely on oxygen now; chat over the intercom mostly focused on instruments and aircraft trim.

Suddenly, Navigator Austin Finely piped up on the intercom: “I have no radio compass capability; it’s malfunctioning.” Short pause. “And my backup magnetic compass is missing. It is not on board.”

Since the weather was thickening below them, it covered any landforms that could define their location above the Earth. As they looked out through the glass of the Flying Fortress, they all knew the truth: they were lost. Radar was nonexistent on B-17s until later that year, and other than the presence of the setting sun in the western skies, they had no idea precisely where they were except by “dead reckoning,” a simple calculation of their direction, based on the sun, and their cruising speed which hovered around 160 MPH.

At 5 PM, Radio operator Morris Becker raised Walla Walla Field with their situation report. A phone call to Gowen Field, in Boise showed that skies were clearing there; the plane could land at Gowen, the Walla Walla tower said. But then First Engineer Henry Van Slager voiced his grave report over the intercom: “We don’t have enough fuel to get to Boise. The bomb bay fuel tanks were not refilled at Walla Walla.”

As pilot Joe Brensinger evaluated this latest issue, further information came in from the engine crew. With the winter-like weather they had encountered with their passage through dense cloud layers, wings were icing up, as well as engine carburetors. The Pratt and Whitneys were misfiring, and not running at peak efficiency.

They were lost, low on fuel, and were losing power and control of the aircraft. And it was getting dark. Finding a place to land with the dense cloud ceiling below them would be impossible. If they broke through the cloud layer, they could easily find the unyielding face of a snow covered mountain in front of them. The crew had flown enough training missions to know that mountain peaks in the Northwest often intersected quite nicely with the cloud ceiling at 10,000 feet.

************

1943 marked a quiet calving season in the high Pahsimeroi, specifically on what is now called Alderspring Ranch, about a third of the way up the high valley. Several spring thaws had already occurred, but winter was fighting hard to maintain an icy grip on the remote mountain country. Red Hereford cows heavily pregnant with soon-to be born calves had just been sorted in the straw covered corrals for the night, when suddenly cows and their human cowhand counterparts looked to the sky.

It had begun as an imperceptible rumble that quietly rattled into one’s consciousness and then became unquestionably real as it came closer. Two pairs of unmufflered Pratt and Whitney engines have a way of doing that, especially when only two thousand feet away, overhead. In the faint light of dusk, the lumbering shadow of a B-17 bomber worked its way up the valley and over the adjacent Pahsimeroi Range, barely clearing the treetops as it motored its way to Challis on the other side.

It was unusual to see one of the big aircraft so low.

***********

The war had been going on for 3 long years, and the war effort affected every resident of the US. Rationing was one way to allow for a steady stream of supplies to the armed forces. It was an easy and dutiful compliance, since most homes had men and women overseas and involved in the fight.

It was Tuesday night, in Challis, Idaho, and it was the night that the rationing board met at the Challis Courthouse. The meeting wore on into the night, discussing the intricacies of rationing everything in Custer County from fuel oil to food. Even sugar and tires required special stamps to obtain.

The quiet of the meeting was suddenly interrupted by the unmistakable window rattling rumble caused by none other than a big bomber. It was 10:00 PM, and the four men stepped out from meeting into the cool and cloudy night. They strained their eyes in the darkness, and soon spotted an aircraft beacon cruising in long circles in the sky above the Pahsimeroi mountain range. It was flying low, and in the twilight of a spring night, it looked too low.

It was.

The four speechlessly watched the big plane auger right into the one of the rocky and timbered flanks of 11,000 foot Grouse Peak, in the middle of the mountain range between Round Valley and the Pahsimeroi.

The men jolted back to life, and immediately telephoned the Sherriff. Within an hour, the Custer County Sheriff and three others set out for the wreckage. In the wee hours of the morning, they were joined by 4 more men carrying backpacks with food and clothing if indeed there were any survivors. After an extensive search around the still-smoking crash site in deep snow, they concurred on their grim findings.

The B-17 Flying Fortress was empty. There was no-one on board.

After evaluating all possibilities, 22 year old Commanding Officer Joe Brensinger decided that the only safe choice for he and his crew would be to bail out. He dropped elevation to 14,000 feet, where his crew could safely take off their oxygen. Any lower, and the Flying Fortress could slam into the side of a mountain.

He then instructed Co-pilot Thompson to set the autopilot on a very slow circling flight pattern and rang the three short rings on the alarm bell that all crew members knew meant to don parachutes. They each had harnesses on from their flight positions; all they had to do was to walk over to their parachutes, clip into them, snap into the static line, and get ready at their respective exit doors.

Sergeant Harry Wiegland, assistant radio operator, was caught in the middle of clicking his Morse code radio transmission, and didn’t finish. “I had just sent out three letters, B-A-I,” he said, “of the message “bailing out,” when I found there wouldn’t be time to finish it.” He just got up from his post, and headed to snap into his parachute. “There was no confusion. Not a word was spoken.”

Each crew member knew exactly what to do, and what door they were to drop from.

As they opened the doors, frigid wind blew in with wildly spraying snow. It was a blizzard outside, with whiteout conditions. But they knew that the alternative of staying on board was unthinkable.

Commanding Officer Joseph Brensinger actuated the second alarm bell. This was a prolonged and unbroken alarm that meant only one thing: abandon ship.

Each of the airmen dutifully jumped into the gray void of the blizzard.

One hundred and sixty mile an hour winds ripped the men from the fuselage of the aircraft, and handily removed one of Co-pilot Harry Thompson’s flight boots. He was stocking footed, and falling from the sky, but as soon as they were clear of the doomed aircraft, static lines ripped their chutes open, deploying them into the sullen and freezing sky of an Idaho snowstorm.

Except for Engineer Henry Van Slager. His parachute may have deployed, but likely not. Perhaps his static line came unattached. He would never be seen again.

It just so happened that they picked one of the remotest regions of the United States to jump into. They were floating downward into what is today the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness, the largest chunk of wilderness in the US other than Alaska. It is a tangled jumble of forested peaks, canyons and rivers.

Miraculously, all survived ground contact with no injuries, especially with the non-directional chutes of the day. All of them landed in forested mountainsides, and somehow managed to find the ground safely. Five feet of snow certainly cushioned impact.

Sargent E.W. Gundman, a gunner from California, found Morris Becker, from Ozone Park, NY in a small clearing. They unclipped from their chutes and started slogging blindly through the deep snow and happened across Radio Operator Wiegland, from Indianapolis. They found walking impossible, and proceeded to let gravity propel them, and actually roll downhill in the heavy snow.

Darkness fell, and they huddled together for warmth in the blizzard, sheltered only by the parachute that Harry Wiegland had handily saved.

The next day, the trio found that following gravity turned out to be their best decision. They ended up at Indian Creek, and there found an abandoned prospector’s cabin, where they found moldy flour, baking powder and a little sugar in the larder. Over a tiny cookstove, they were able to get some sustenance for their trek down the wide creek. They attempted to build a log raft to float down the creek, but found it would not support them, and scrapped the idea for a wet wintry slog down icy waters until they hit the Middle Fork of the Salmon River.

In the gathering darkness, they spied a tiny but warm light on a timbered bench above the river. After calling out and stumbling through the underbrush, they discovered a ranger cabin, lit by candlelight, and occupied by two more of their companions, Co-pilot Thompson, and Navigator Finley.

“Boy were we glad to see him!,” said Sargent Wiegland. “Especially when he told us that the ranger cabin was stocked with plenty of food.”

They could wait there for the rescue party that surely would find them.

After all, they had already been pinpointed by a small backcountry airplane, piloted by a local mountain pilot, named Penn Stohr. Mr. Stohr spotted both of the first cabin occupants on separate occasions and dropped notes out of his aircraft window with rendezvous instructions. One of the pilots later marveled at the amazing aviation skills displayed by Stohr, especially given the mountain landscape they were in: “He [Penn] flew over us and dropped a note. It landed right where we were standing. Man, that fellow could be a bombardier. He’s certainly got an eye for it.”

Six days after bailing out of the “Fort,” (airmen’s nickname for the B-17 Flying Fortress), one of the men noticed electrical wires leading out of the ranger station’s dead phone system. They joined in a nearby Ponderosa pine tree, where upon closer inspection, there was a switch. He climbed up to it and closed the circuit.

Immediately, the ranger station phone started ringing. Austin Finley reached the phone first, only to interrupt two women in conversation. It was what was known as a party line, that had somehow stayed intact through the winter of miles of Idaho wilderness despite heavy snow. Generally, such phones were used for fire lookout communication during the summer season in the remote mountains.

Two other men were picked up at another backcountry airstrip, and the Commanding Officer, Pilot Joe Brensinger, of very temperate and non-snowbound Alabama, was picked up by another rescue plane after walking over 30 miles through deep snow. Apparently, as he was the last to leave his ship into the sky blizzard, it left him separated by miles of broken mountain country from his crew by the time he met the ground. He was alone, and though unhurt, was suffering from hunger and exposure.

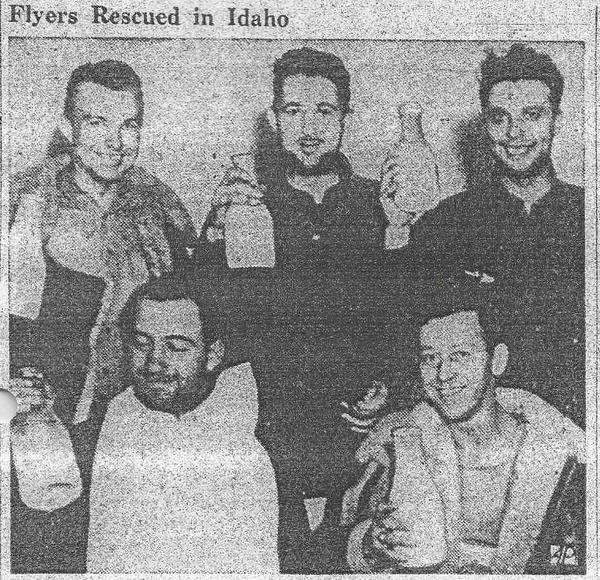

All of the survivors found their way to hospitals to be treated for exposure and frostbite, and even stocking-footed Harry Thompson kept all of his toes.

Sadly, now that the Greatest Generation is largely passing in front of us, we easily forget what a country looked like in the turmoil of war. It reached all parts of our nation; certainly in loss of life, and the changes in perspective and lifestyle. In just a few days, we’ll remember that “Day of Infamy,” on December 7, when Pearl Harbor was invaded, and we were launched into a war we were completely unprepared for.

But in our mind’s eye, we can go back, particularly when things trigger the memory and the story.

From the Ranch headquarters we can see where this small scrape with the war unfolded. Grouse Peak stands to the southeast, now cloaked with a solid crust of winter snow, rearing high from the valley floor. And to the West lies Hat Creek, our summer grazing range, which is one ridge away from the River of No Return Wilderness, and 30 miles from where the men found the Middle Fork of the Salmon River.

The country is just as it was when those airmen found it. It is all still untracked wilderness, now formally designated as such, forever. At this time of year, the wilderness is sealed tight from all but the most intrepid humans by deep snow and frigid cold. It is only home to the denizens of winter: wolves, wolverines, pine marten and, in the lower elevations, elk and bighorn sheep.

And the B-17 Flying Fortress, #42-29514? It is still up there at nearly 9000 feet elevation, on the shoulder of Grouse Peak, albeit completely shattered in pieces and strewn across a mountainside.

Ethan, Josh and the girls and I hope to ride horseback up there to find it this coming summer. We’ll send you some pictures.

Happy Trails.

Glenn, Caryl, Girls and Cowhands at Alderspring

Kevin Brensinger

Good day,

My grandfather was the Commanding Officer, Joe Brensinger. I am Kevin Brensinger, retired in 2018 from the US Coast Guard. I’ve heard versions of this story but this is absolutely fascinating. I would love to plan a trip there from Texas to possibly visit the crash site as well as the Ranger Station.

Caryl Elzinga

Kevin

This is really incredible. I would really enjoy visiting with you about this! The crash site I believe is indeed visible from the ranch, but dang hard to get to. The ranger station I’d have to check into. I don’t know if the buildings are still there. Many of the FS remote outposts were taken down over the years. Keep in touch!

-Glenn

Kevin Brensinger

Glenn,

Visiting with you about this would be truly amazing! I am trying to plan a trip up that way within the next few months before it starts getting cold. Thanks for your reply. My phone number is 251-366-8538 if you wanted to call or text

Cari Hudson

I was raised on a ranch east of Idaho Falls. Very similar to your area. We did not need to heard the cattle bus spent lots of time with them. They felt like our buddies. I’ve driven through your area many times and love it too.I miss those days and am a bit jealous of you and your outfit. I’ve been reading your stories and seeing your photos and am wondering if you need an old lady to ride heard. What a lovely way to raise a family. Blessings to you and a life if adventure and fun and friends. The hard work does not matter when your happy and can spend it with a bunch of contented cows, challenging work and a wonderful family.