Breakfast trout; specifically, Dolly Vardens. It’s what 20-year-old Frances Alder would soon have in her creel. The year: 1948. The war had just ended a few years back, and she and her new husband, Ron were working a grubstake all their own in the mountain country of Idaho. They didn’t have more than a few dollars to their name, but that didn’t matter. They had both spent all their childhood living and working on the land.

And they were free. And that meant a lot, especially to Frances who had happily escaped from a sort of slavery. She and her brother were half Nez Perce orphans, raised by the State in a hardscrabble facility just off the Nez Perce Reservation lands in North Idaho. There, at the age of 7, she and her blood sibling were happily adopted by a potato farming couple from Lemhi, Idaho. The grinning and fast-talking farmer said that she would fit right in with his own children and have a wonderful, wholesome life on their farm along the curve and bubble of Hayden Creek.

The hope of a warm and friendly abode started to fade when they were dropped in the wet straw in the open bed of the 1922 Model T pickup for the long and cold ride to their new home. Things got worse once they arrived. It was springtime, and potatoes needed to be put in the ground. Frances and her brother and a few other adoptees like them were conscripted into the endless work of planting and hilling spuds on a hundred acres. And that was just the beginning. Ditches needed cleaned, water run, and weeds hoed. Long days in the hot high-altitude and skin burning sun were spent at the end of a hoe with blistered hands while the farmer’s own offspring played in the yard around the white clapboard house.

It was 1935, and slavery was alive and well in Lemhi, Idaho.

And now, finally, after over 10 years of servitude, she was her own. She ran a comb through her Nez Perce black hair, and was happy to be up before the sun, again, out of the cabin, bundled in ragged sweater and well-worn chore coat, into the gray light of early morning while Ron milked the cow. Frances loved to fish, and her time alone, and frankly had had enough of humanity. Ron was the only exception.

In her leaky gum boots, she ventured downstream into the small canyon where the East Fork and Main Fork of Cow Creek converged; there would be more water and deeper holes in the beaver dam meadows that remained.

There were no more beavers—they had been for the most part trapped out of the country 30, maybe 40 years ago. But their signature dams still remained, at least in part holding some of the water in tiny ponds as the 4-foot-wide ribbon of water called Cow Creek stair-stepped its way off the Continental Divide toward the confluence with Agency Creek. And in those ponds lurked many Dolly Varden trout.

Frances knew the trail, as she tried to make it most mornings now that snowmelt flows had finally receded. As she picked her way down the game trail along the creek, she heard a whinny, and then a snort. A band of wild horses on the ridge above spied her in the low light, and she could see them silhouetted against the dawn light of the eastern sky. She and Ron shared the valley with them, and no-one else.

The Dollys were plentiful in those days, but their populations have dwindled since that time due to habitat alteration from poor logging practices and overgrazing of riparian habitats. Clear gravels were what the fish needed to spawn successfully; silty and muddy ones suffocated the eggs while they incubated. Then in 1980, with the stroke of a pen, piscine taxonomic splitters changed Idaho’s Dolly Varden nomenclature to new name in this region of the northern Rockies: Bull Trout.

The two fish are strikingly similar and are only consistently told apart by DNA testing. I personally wonder if name change was because Northwest taxonomists were a little embarrassed by the origin of the Dolly Varden name. It is unusual, to say the least, and finds its earliest use in a tale by Charles Dickens. In Inland Fishes of California, author Peter Moyle recounted a letter from Mrs. Valerie Masson Gomez:

“My grandmother’s family operated a summer resort at Upper Soda Springs on the Sacramento River just north of the present town of Dunsmuir, California. She lived there all her life and related to us in her later years her story about the naming of the Dolly Varden trout. She said that some fishermen were standing on the lawn at Upper Soda Springs looking at a catch of the large trout from the McCloud River that were called ‘calico trout’ because of their spotted, colorful markings. They were saying that the trout should have a better name. My grandmother, then a young girl of 15 or 16, had been reading Charles Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge in which there appears a character named Dolly Varden; also, the vogue in fashion for women at that time (middle 1870s) was called ‘Dolly Varden’, a dress of sheer figured muslin worn over a bright-colored petticoat. My grandmother had just gotten a new dress in that style and the red-spotted trout reminded her of her printed dress. She suggested to the men looking down at the trout, ‘Why not call them “Dolly Varden”?’ They thought it a very appropriate name and the guests that summer returned to their homes (many in the San Francisco Bay area) calling the trout by this new name. David Starr Jordan, while at Stanford University, included an account of this naming of the Dolly Varden trout in one of his books.”

“A dress of sheer figured muslin worn over a brightly colored petticoat?” Really? This the origin of the name of a great fish of the Rocky Mountains? Named by a woman? Hardly appropriate, perhaps their staid piscine taxonomist minds considered. So maybe they preferred the much simpler, more masculine sounding “Bull” trout.

I prefer Dolly Varden, myself. Elegant beauty conveyed.

These lovely and beautifully named fish made their living high on the hog when the salmon and steelhead returned to the canyons and creeks of the long Lemhi Valley, where Agency creek joined the Lemhi River. After two years in the broad Pacific, millions of fish traveled the 900 miles up the Columbia, Snake and Salmon Rivers, like on pilgrimage to their birthplace to spawn. And tens of thousands made a left turn up the Lemhi. And of those, a few hundred headed up Agency Creek. There, they created redds, or spawning beds in the gravels shadowed by Idaho’s high divide with Montana, laying a multitude of eggs in the gravels.

And waiting for them were hungry Dolly Vardens, who would feast on the incredibly protein and fat rich eggs not promptly covered in gravel by the powerful tail swishing of the 3- to 4-foot-long Chinook hens.

Then, returned Chinook salmon hen and her buck would die within days, leaving thousands of fertilized eggs to live in gravels for the winter.

Dolly Varden, who didn’t migrate, would now be elevated to a fit and fleshly condition where they could survive in the cold waters of winter—often under ice, where they got by on the lean offerings of occasional nymphs, aquatic bugs, and juvenile sculpins.

And then, after wintering, sustaining, and making a living through ice and snow, after the turbid rush of snow and ice melt, after dining on the millions of hatching insects that fed them again with abandon, the fish became food themselves after falling for the ruse borne by Frances’ bamboo fishing pole: a grasshopper or red wiggler worm, dug from the black soils along the East Fork. And so, Fran foiled 2 or 3 fryers to later settle in a bacon fat bearing cast iron skillet on the two-plate stove they had packed in by horseback to their cabin just last fall.

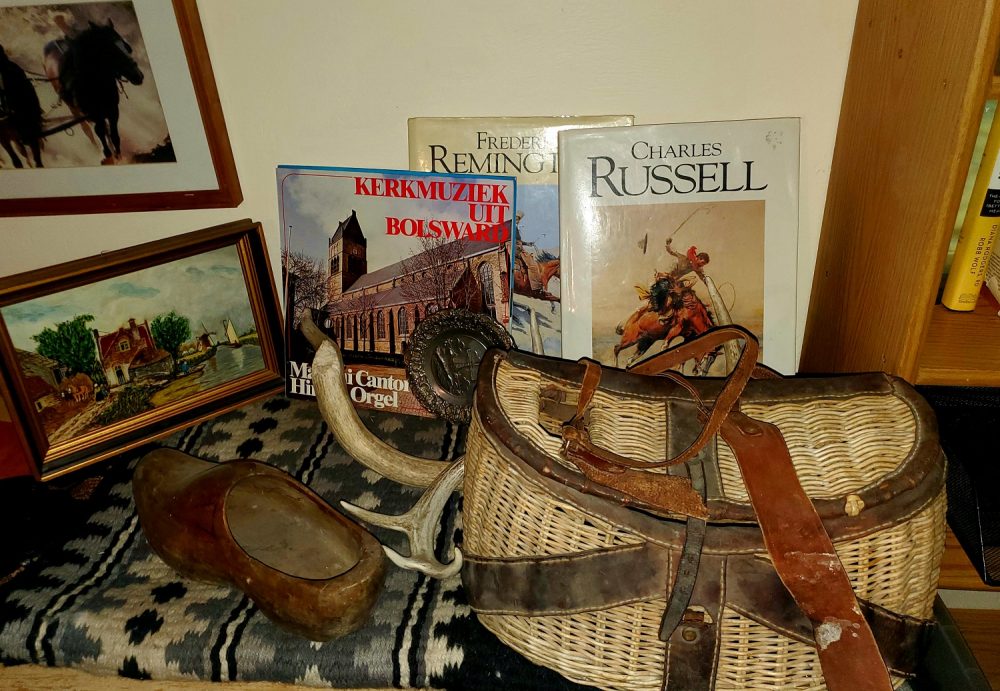

She respectfully placed her catch in her creel padded with pinegrass wetted by the waters of Cow, and made her way back to the little shack, hewn out of nearby Douglas-fir Ron had felled and stacked last summer. He was good with a singlebit and could do anything on a horse, despite being only 21 himself. Too young for the war, thankfully, as many friends and family they both had known never returned, and now rested under marble markers in neat rows in places like Normandy and Verdun.

There was one room in the cabin, and Frances fried her catchlings in a bit of bacon grease saved from side meat cured themselves. With it, they would have Johnnycake and milk, and fresh churned butter. This was life for them. A few cows that Ron ran out the back door would raise calves for market in the fall to provide a small wallet of cash that could buy flour, salt, and other dry goods for the winter ahead.

And he already planned on helping Earl Payett up Agency Creek, their nearest neighbor just about 7 miles distant by horseback, with his haying of the broad meadows of the upper Agency valley. They would stay there until snow flew, and then would winter down back in the Lemhi Valley, with Claude and Josephine Alder, Ron’s parents on their ranch. This particular ranch where Ron and Fran wintered would many years later be called Alderspring, after the Alders themselves, and the clear ice water spring that emanated from the base of the Divide foothills at the foot of a copse of alder trees.

Spring turned to summer, and summer meant hay. The couple moved to a bunkhouse on Earl’s place, where they both helped mow, rake, and stack hay with teams of horses. The work took them to fall firewood gathering and bringing weaned calves to market. Then, before Ron and Fran were able to head down canyon just 7 miles to his parent’s ranch to winter, a blizzard hit, depositing 4 feet of snow up Agency Creek.

Where the canyon necks down below the Payett place, a pair of cliffs stand at the foot of steep mountain slopes and pinch Agency into a tiny cleft, where trail and creek pass together through a 15-foot opening. There, even today, as a traveler sojourns through on what is now a jeep road to Lemhi Pass and Montana, if they look very carefully on the north wall, they can see where Shoshoni natives painted the rocks with telltale vertical smudges of ocher. Why they applied the paint remains a mystery, but perhaps they knew that these narrows would be the place that nature would have final say.

It was here that in 1907, Chief Tendoy, the spokesperson to Washington DC and de-facto leader of the Lemhi Shoshoni, or Agaidika was found dead, face down in the shallow waters of the creek.

It was also here that the blizzard deposition of massive quantities of snow avalanched down the mountainside and literally buried the canyon trail under a 40-foot matrix of snow and debris. Passage was impossible by horse or by foot. The Alders and the Payetts were stranded there for the entire winter, with no access to outside food, communication, or supplies.

When I asked Ron and Frances about it over coffee one day, they were fairly matter of fact about it.

“We just made do,” Frances told me. “We had plenty of flour and cornmeal, and we butchered a cow, and had a hog hanging. We even had our milk cow and some chickens.”

“And we had plenty of wood,” Ron quipped. “Earl and I had to crosscut and chop it all by hand, but it kept us warm.”

They just made do. I am not sure we could have. I’m not even sure many of us have the knowledge or skills to.

But they did. They were part of the greatest generation. It’s called that, you know. Caryl and I are boomers, and most of my kids are millennials and Gen Zs. And when you check it out on google, their gen was the greatest. It was simply that.

I’m so grateful that we could learn from them.

Happy Trails.

Jennie Smith

I enjoyed this story – thank you for sharing it. I have wondered where you he name of your ranch originated and now I know this very interesting answer.

🤗

Alma Christina Sychuk

Alderspring Ranch,

How interesting to follow the trails re: the early American and or Canadian settlers; most of us, (American/Canadian) hail from European stock—- don’t we?

My American grandparents (Minnesota) crossed the Canadian border to farm in what was then the Western part of Canada, the province of Saskatchewan.

The Barthels were German Catholic.

They like many others Minnesotans established towns like Fulda and

Humboldt where my father, Herbert was born (1911) and raised.

Lorenz Barthel was fortunate in that he qualified for a section of land (Homesteading ended 1929) and raised 9 children: 4 sons, 5 daughters.

each son was allocated a quarter section.

My grandfather rode horseback a great distance to St. Walberg to pick up the mail (temperature at times were 40 degrees below zero) and deliver to Barthel’s homestead where Grandmother served the community as Postmistress; today Barthel, Sk can be found on SK map.

Herbert Barthel (eldest son) married Medora Picard in 1932; Alma Christina was born (eldest daughter and grand-daughter) in 1934 on our quarter section of land identified by birth certificate: Township/section/plat map; siblings born in Loon Lake.

I met and married Peter Sychuk (Ukrainian parents who during the Russian Revolution immigrated via Poland to Canada in 1929 and settled in Ukrainian section near Prince Albert,

The Canadian and American developments were identified in early 1900s

as ethnic communities: French, German, Scandinavian, Yugoslavian, Italians, and Spanish not overlooking the many Iris /Scottish and notable English.

.

Separated by a great distance where the roads were not paved leaving traveling treacherous at times. However, following WW II armistice in 1945 the indispensable car became more affordable allowing for the different nationalities meet and mix.

Life changed: for many people many new inventions made life a little easier

like the washing machine and sewing machine for women and the men had their machines also.

In 1953, Peter was transferred from Vancouver, B.C., TO Las Angeles, California; we bought our first home in Temple City, CA; it was 1956 and our daughter, Darcelle was age 2.

We retired to Green Valley, AZ in 1995 where my two children and two grandchildren presently reside.

It is amazing that 87 years can begin in a log cabin and end up in a tech world of computers and iPhones.

Where do we go from here?

I enjoyed your history and couldn’t resist the temptation to relay mine.

Thanks for sharing your history.

Best regards,

Alma Sychuk (nee Barthel)

Green Valley, AZ

ps

Your farm-raised animals gives me great pleasure at mealtimes where I know that the meat/chicken I bought from Aldersprings Ranch is raised on a farm where only a Farmer like you and my grandparents appreciate God’s natural wonders beginning with the ‘Good Earth.

Thank God for the early pioneers’ steadfastness in farming

and the many blessings we received in return.

Best regards,

Alma christina Sychuk (nee Barthel)

Green Valley, AZ 85614

David Wagner

Happy Easter !!

I love stories of the past. I learn much from them.

Pam Dugger

Thank you for this wonderful story!

Andrea

Such a beautiful story, I enjoyed it so much. Thank you for sharing